Algeria: The secret service never dies

ALGIERS - By sacking high-ranking officers and dismantling the Algerian Department of Intelligence and Security (DRS), President Abdelaziz Bouteflika may think he has eliminated the military officials who have put him in power. However, in Algeria, as elsewhere, men disappear, but the system remains.

In Algeria, the plot cannot even compare to the best American thriller series. Plot twists, power plays and myths - all the ingredients of a great political thriller are present and all are fed by a code of silence to give a fictional sense of the power struggles at the top echelons of the state.

The cast is dominated by the two key political figures of the country. The first, President Abdelaziz Bouteflika, 78, has served four terms in office and spent 15 years in power, despite being in a wheelchair since his stroke in the spring of 2013.

The other, Mohamed Lamine Mediene, 76, is nicknamed Toufik, and has long been the intelligence services’ invisible chief. He has headed the DRS for over 25 years. Until last week, when a photo of Toufik was published in Algeria’s En-Nahar newspaper, the last known picture of him dated back to late 1990s.

These have long been the two faces reflecting the two-headed Algerian system, but that all changed on Sunday when Bouteflika replaced Toufik.

According to one advisor to the head of state, this will tip the balance of power in favour of the presidency.

"Since he is at al-Mouradia [presidential] palace, Abdelaziz Bouteflika has been trying to turn the Algerian regime into a civilian power," the advisor, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, told Middle East Eye.

Mourad Goumiri, president of the Association of Algerian Academics for the Promotion of National Security Studies, told MEE that Bouteflika “never forgave the army”, particularly the military’s security, that excluded him in the late 1970s from becoming president after Houari Boumedienne, the spiritual father of the Algerian army.

When Boumedienne died in 1978, Bouteflika saw himself as his legitimate heir. He read Boumedienne’s funeral oration, a role traditionally reserved for person who will replace the deceased. But the army and the “Sécurité militaire” took a different position.

Kasdi Merbah, head of the powerful Sécurité Militaire, the forerunner of the DRS, and then-chief of staff of the military, judged Bouteflika as “too lightweight”, too liberal and too connected with foreign countries to succeed Boumedienne, Goumiri said.

"It seems that the profile built by the intelligence about Bouteflika designated him as not being 'trusted' enough and too much 'linked to foreign powers'. This setback had deeply affected him,” he said.

Boudiaf and Tibhirine

For the political scientist Louisa Dris Ait Hamadouche, "this civil-military rivalry, a characteristic of a system that has never been and never had the intention of becoming monolithic, is not exclusive to Bouteflika and Mediene”.

Ait Hamadouche said the rivalry, in fact, goes back to 1956 and the Soummam Congress which was held to organise the young Algerian revolution against French colonialism and impose the rule of the "civil supremacy over [the] military".

The congress also sought to limit, even then, tensions between the two trends dominating the Algerian nationalist movement that had become divided between the exiled leadership and supporters of Ahmed Ben Bella who became Algeria’s first post-independence president.

For 50 years, a balance was found between the army and powerful secret services, heirs of the war of independence, and strong civilian power embodied by the president. This delicate balance was broken in the 1990s: the absence of civilian power against the Islamist insurrection left Toufik and the chief of staff, who had been managing the war against armed Islamists, very powerful.

But eventually, by 2013, the balance of power between the two, said Ait Hamadouche, tilted back into Bouteflika’s favour by 2013 when he started to attack the DRS.

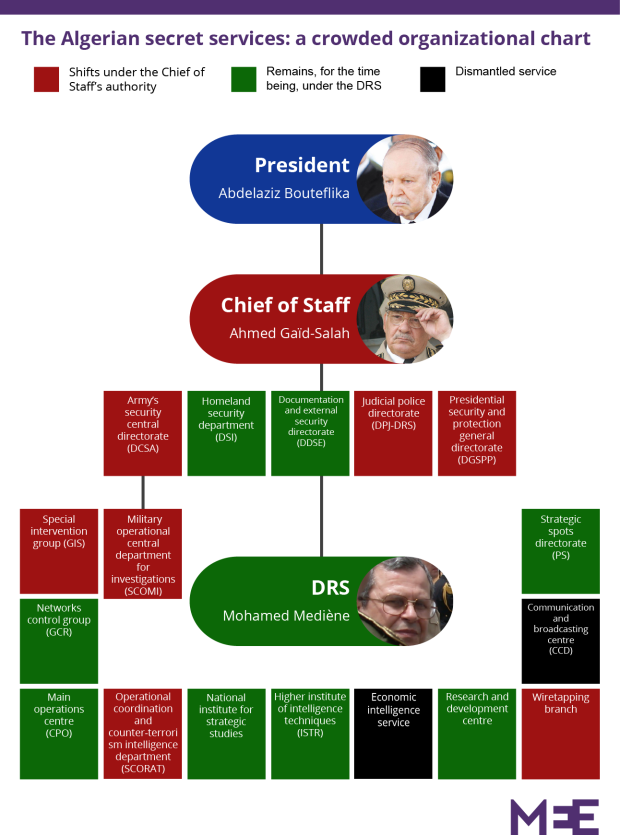

After returning from a long hospitalisation in Paris that year, Bouteflika launched his first strike. He transferred the responsibilities the DRS’s media monitoring centre to the general staff of the army whose chief, Ahmed Gaid Salah, is a friend of the president. Bouteflika did so because he suspected the DRS of having leaked information in the media about his incapability to govern because of his illness after a nearly 80-day hospital stay.

He then turned on the DRS’s judicial police. Since 2009, the agency had been investigating corruption scandals including contracts of the public company, Sonatrach, which was led by then minister of energy and friend of Bouteflika’s, Chakib Khelil, and also questions surrounding the contracts for the building of the East-West highway.

These investigations indirectly involved individuals who were close to Bouteflika, including the Sonatrach investigation which led to the imprisonment of several leaders and, according to local reports, was alleged to involve Bouteflika’s brother, Said.

A new secret service, dependent on the army’s chief of staff, called the Military Operational Central Department for Investigations (MOCDI), was also established by the chief of staff from the DCSA, the army’s security unit which now also supervises the Counter-Terrorism Intelligence Department (OCCTID). Last August, even the mythical DRS armed wing, the Special Task Force (STF), fell under the ground forces’ command.

Thus - at first glance – only three important services remain attached to the DRS: the country’s counter-intelligence agency, the Directorate of Territorial Surveillance (DST); the General Directorate for External Security (DGSE), a foreign intelligence service equivalent to CIA or MI6; and the Directorate of Strategic Spots, an agency monitoring institutions, political parties, trade union and ministries by assigned agents.

FalconsIn addition to the dismemberment of DRS agencies, some changes in top posts this summer including major-generals Abdelhamid "Ali" Bendaoud, who was chief of the counter-intelligence, and Djamel Kehal Medjdoub, head of the presidential guard. Both were removed from their posts in late July after a mysterious report of "shots" were heard at the presidential residence. Then came the arrest at the end of August of Major General Abdelkader Ait Ouarabi, who was in charge of counter-terrorism at the DRS.

"It's true, Bouteflika never liked the military and he never hid that fact," a close associate to the presidential circle told MEE. The source, who preferred to remain anonymous, cited Bouteflika’s famous phrase back in 1999 when asked about his power possibly being curbed by the generals who had brought him to power: "I do not want to be a three-quarters of a president.”

In 1994, the generals considered having Bouteflika preside over Algeria in the war against armed Islamists. At the time, Bouteflika asked to become the country’s defence minister or army chief, knowing that if he did not control the army, he would have no power, only a façade of power. So the military chose one of their own, General Liamine Zeroual, who ruled as president from 1995 until 1998.

But even before Bouteflika started to pull back the power of the DRS in 2013, there was also a major shift in 2004, a source told MEE. At that time, Bouteflika’s campaign manager, head of government and right-hand man, Ali Benflis, under the influence of the chief of staff’s hawks, ran for presidential election against Bouteflika.

"Bouteflika finally overcame the plot, but he never forgot that betrayal,” said the source.

"Since the military brought him to the presidency in 1999, Bouteflika has continued to eliminate those who enthroned him, including civilians but also - and especially - military figures, and first in line was Larbi Belkheir," said the academic, Mourad Goumiri.

Belkheir, president Chadli Bendjedid’s chief of staff in the 1980s, was called the "Cardinal of Frenda" from the name of his hometown. From the 1980s to the 2000s, he was the most powerful man in Algeria and considered the "Godfather" of great generals, including Mediene – until Bouteflika pushed him aside.

"This strategy has enabled him [Bouteflika] to renew his term four times with the decisive support of the DRS, including during the third term when he had a constitutional revision,” Gourmi said.

But Hamadouche stressed that even if the head of state has "always had the inclination to get rid of the influence of the army," one cannot conclude he has succeeded.

"Until proven otherwise, and even if Gaïd Ahmed Salah, the army chief, is close to the presidency, the DRS have been attached to the chief of staff and thus remain within the military, under the same roof. The supremacy of politics over the military would imply the existence of civilian control of the military means, such as commissions to foreign affairs or defence. "

The political science professor also points out that, with the exception of the 1990s, a period that witnessed the DRS’s "transformation into a super structure to fight terrorism," the chief of staff has always been in power.

"We remain in a complementary-rivalry relationship; a characteristic of all developing countries that are unable to complete their democratic transition,” she said.

The system’s backbone

A DRS official told Middle East Eye that the intelligence service will prove hard to eradicate.

"How can you destroy services that do not even officially exist?" he said sarcastically, citing the fact that the decrees that gave birth to the intelligence services departments were never officially published.

"Bouteflika may decide to play with or change their direction. However, he could not take away their influence," the official added.

This view was shared by a former official with the Ministry of Armament and General Liaisons (MALG), which led the battle against the French during the country’s war of independence.

"The Algerian services over took the president, and even Mediène, who was only a caretaker. It is one step in their long transformation since the end of the late 1950s. Algeria had a powerful army and a powerful secret service even before being a state,” the MALG official said.

"This is the system’s backbone. Despite the hostility against the DRS or Mediène’s power, the presidential circle is aware that losing this unit would weaken its grip on the state and society."

"Remember that when Bouteflika himself was in high school in Morocco, he was recruited in the National Liberation Army by Abdelhafid Boussouf... the founder of the Algerian services,” the official said.

A retired DRS officer admitted that the situation is not as clear as it seems: the "apparent" dismemberment of the DRS is occurring at the end of a reign, in a climate where the succession, not only Bouteflika’s but also Mediène’s and Gaid-Salah’s, provides material for speculation in Algiers’ salons and foreign embassies”.

Current tensions, he said, are only the result of a "consensus deficit" on the succession scenario of the three institutions at the helm of power - the president, army and DRS.

"By waging war on the generals, Bouteflika has broken the sacred rule of collegiality of decision-making. By trying too hard to be the king and protect his 'corridor'', he massacred all the knights. In chess, it's called a dead end."

This article was originally published on Middle East Eye's French page on 9 September 2015.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.