ANALYSIS: Diplomacy could curtail Libya humanitarian disaster

United Nations-mediated peace talks for Libya hang in the balance this weekend after a frenetic fortnight has seen efforts to bring all sides to the table fail.

Bernadino Leon, head of the UN Libya Support Mission (UNSMIL), hopes to convene the talks to tackle worsening fighting across the country, itself triggering a growing humanitarian crisis with hundreds dead and 400,000 displaced.

Leon had been trying to bring the sides together since September, and on 10 January announced an agreement to meet in Geneva. The announcement brought strong international support, with the US State Department issuing a statement jointly with Britain, France, Italy, Germany and Spain, welcoming the move. European Union Foreign Policy Chief, Federica Mogherini underlined international concern by declaring: "This represents a last chance which must be seized.”

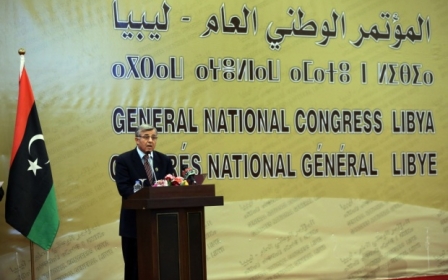

However, one of Libya’s two rival governments initially refused to take part; The Tripoli-based General National Congress (GNC) declared it would not be sending a delegation to Geneva for the start of the talks, and would debate the matter on 18 January.

Leon opened the talks despite this on 14 January, with Libya’s second government, the internationally recognized House of Representatives (HoR) based in Tobruk, in attendance. Despite only one government being there, Leon insisted he was encouraged, because a number of other political actors and civil rights officials attended. “It is not one camp that is refusing to come and the other camp is here today. We have many people from both camps here,” he said.

Proximity talks

The discussions, held in the UN’s lavish Geneva headquarters, were described as “proximity talks”, in which groups were free to meet in separate rooms, with UN officials shuttling between them. Leon made clear that any decisions taken in Geneva would first have to be agreed back in Libya. “This is a process,” he explained, “It's going to take time. We're not expecting to have a breakthrough, no immediate decisions.”

After two days of discussions, delegates flew home and Leon headed for Turkey for meetings with Nuri Abu Sahmain, head of the GNC. On Sunday, 18 January, the GNC met and decided to support the talks, but only if they were switched from Geneva to Libya, suggesting the southern town of Ghat as the venue.

The same day, both Libya Dawn and HoR forces announced ceasefires, the HoR excepting what it called “anti-terrorist” actions against Ansar al-Sharia in Benghazi and militant units in Derna.

The following day Leon announced there would be no more sessions at Geneva that week, while he began meetings to get all sides to agree on a Libyan venue - in effect, talks about talks.

By then, the ceasefire declarations were already a memory. Battles began in western Libya between Libya Dawn units and pro-HoR forces from the town of Zintan. Fresh skirmishes then broke out near Es Sider oil port, while HoR forces launched a new offensive against Ansar al-Sharia in Benghazi. Each side accused the other of breaking the ceasefire, but it hardly mattered; Libya was back at war.

Then on Wednesday, the GNC announced it was pulling out of talks altogether, citing violence by its opponents. Specifically, the GNC accused forces of the HoR of occupying the premises of the Benghazi branch of the central bank. “There has been an escalation of fighting in the past two days,” the GNC said in a statement.

The announcement left the peace talks once more uncertain, set against a background of worsening violence.

Worsening war

What many are calling Libya’s civil war erupted in July, when Libya Dawn, an alliance of militias loyal to the GNC, seized the capital, accusing their opponents of betraying the goals of the 2011 revolution against the regime of Muammar Gaddafi.

Fighting has raged since then across several fronts spanning much of the country.

In addition to the casualties, estimated to be in the hundreds, the fighting has interrupted oil production, Libya’s principle source of revenue. The state-run National Oil Corporation said this week that production is now 350,000 barrels per day, down from the 1.55 million that is the normal export quota.

This fall in income has brought warnings from the Central Bank of an impending financial crisis. The six months of war was preceded by twelve months of oil strikes, seeing revenues plunge from 59 bn dinars for 2013 to just 20.9 bn last year. The bank has been meeting its spending, of 57 bn dinars last year, through use of foreign reserves, but says these are depleting fast.

With most Libyans now depending on payments from the state to survive, the cash crisis is acute. Tripoli’s main airport is in ruins, and Turkish Airlines, the last foreign carrier to serve Libya, suspended its service in January, after Tobruk air force jets bombed the airport at Misrata, the third largest city. In Tripoli, the sight of a dozen or more cargo ships bobbing at anchor waiting for berths to land their cargoes beyond the breakwater is a distant memory as trade dries up.

Financial crisis

Both governments have announced sharp measures to cut costs. In Tobruk, HoR Prime Minister, Abdullah al-Thinni said his administration is presently relying on a 250 million dinar loan from a commercial bank, and declared some foreign embassies would be cut or slimmed down as part of cost-cutting measures.

In Tripoli, the administration of GNC-appointed Prime Minister, Omar al-Hassi has begun a programme of tightening up payments of state salaries, demanding identity cards be produced for payments to cut possible fraud.

Yet both governments know this cannot go on: The IMF estimates Libya’s total foreign assets at $100 bn, but it is unclear how much of the total are in assets that can be quickly turned into cash to plug the revenue gap.

Leon remains publicly optimistic, telling London’s Financial Times this week that his priority remains getting agreement from both GNC and HoR for a unity government, followed by a ceasefire. For that to stick, he called for international troops. “The UN will need to have monitors on all ports, airports and country entrances,” he said.

Italy has repeated its willingness to commit troops to a mission, provided it is mandated by the UN and provided other nations also take part, but other states seem more reluctant, fearing the peacekeepers may be embroiled in civil war.

Legitimacy argument

One problem facing Leon is the fragmented nature of both governments, each a collection of political and tribal forces, and relying on a galaxy of separate militias. Each government is also insisting that it be accorded sole recognition. The HoR, elected in June, insists its position as the internationally recognised government needs to be acknowledged by its rival. The GNC, which was dissolved prior to the June elections until it was re-formed, insists it is legitimate because a Supreme Court ruling declared the June elections, and thus the HoR, invalid.

Leon hopes to side-step legitimacy arguments with his plan for a unity government, which would unite Libya until a new constitution - being prepared by a commission in the eastern city of al-Beida - is ready to be implemented.

On Friday, a fresh twist came, with the UN announcing that there may be new talks after all - back in Geneva. Spokeswoman, Corinna Momal-Vanian said it was a “possibility” with more discussions needed around the problem of convincing both governments to attend.

Optimists hope the talks process is back on track, and that Leon can implement a plan to include militia chiefs and municipal council leaders to get a broad consensus. Working against him is diminishing credibility for a talks process that has seen little progress and many delays. But all sides know they are working against the clock. If the money runs out before a deal is done, Libya will be facing not just war but a humanitarian disaster, pressing a fresh problem for the outside world.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.