ANALYSIS: Hamas stands at a crossroads. Which path will it take?

The rallies were subdued, as were the messages. It was perhaps no surprise - no one considers 28 a milestone anniversary. But for Hamas, its 28th year has been of great significance, and the decisions it takes in its 29th could define its future, or condemn it to darkness.

Many commentators are now asking whether the future will bring more war or a possible easing of tensions with rival Fatah, other Arab countries and possibly even Israel and the West.

Born from a schism in 1987 that ultimately fractured the Palestinian cause, Hamas has grown from a grass-roots religious movement to the governing authority and military force in the Gaza Strip, but remains largely friendless in the region and a pariah on the international stage.

Three wars, the ongoing Israeli and Egyptian blockade and international isolation have all taken their toll. Its path of resistance against Israel and, indeed, other Palestinian factions, has left it desperate for support and cash. Some regional states have reportedly pulled their support, while other benefactors as well as aid groups have had a harder time getting cash in in recent years.

While thousands of Gazans took to the streets last Friday and Monday to mark its 28th year, Hamas cancelled its larger centralised anniversary events, citing other priorities for what little money it has.

Three stages of Hamas

According to Palestinian academic Nafed Aljeab, Hamas has moved through three distinct evolutionary stages. It was closely tied to the Muslim Brotherhood movement at its inception, and built its support through mosques and the community.

Later, Hamas focused on building charitable organisations and providing what others could not, in response to a growing feeling of corruption in the established Palestinian leadership and as a response to the tightening of Israel's grip on the Occupied Territories.

Emboldened by its success, Hamas was able to stand and win in the 2006 elections and, after kicking Fatah out of Gaza in a military confrontation in 2007, found itself in control of the territory and facing the challenge of effective government - its third stage.

Its growth in power has also been a key vulnerability seized on by its enemies, as they deprive Hamas of funds to run Gaza, blockade the strip to steadily choke it to death, and ostracise and ban its leadership from travel.

After being ejected in 2007, Fatah ordered its civil servants in Gaza to stop work. Funding from the PA was cut, with Israel enacting a blockade.

While the election of the Muslim Brotherhood's Mohamed Morsi to the Egyptian presidency in 2012 helped ease the situation, his successor Abdel Fattah al-Sisi later cut the Rafah crossing, depriving Gazans not only of their one way out, but also the only route in for foreign funding.

Hamas' response, for years, has been brutal, recalcitrant and costly to all sides.

But there are signs that its leadership wants to move past the last decade of defiance and conflict, to a future of co-operation and rapprochement. There can be no doubt that it has been pushed in this direction, in part, by its lack of money and allies, and a growing list of enemies.

Thawing relations

After years of hostility with the powers in the Occupied West Bank, Hamas has begun to soften. The National Consensus Government was agreed last year with the Palestinian Authority, a move analysts said at least showed a willingness by Hamas to mend ties, although it remains staunchly opposed to being told what to do in Gaza by an outside force.

That agreement now hangs by a thread, however. Only on Monday, Hamas condemned the decision of the Palestinian President, Mahmoud Abbas, to install three new ministers without discussion, saying that it did not recognise the appointments, and would "deal with them as average citizens".

Its willingness to go to war with a far more powerful enemy, Israel, has led to three disastrous conflicts since 2008 in which thousands of Palestinian civilians have died, the worst coming in 2014.

But since then, it has engaged in indirect talks with Israel - a first for the group, despite its stated firm opposition to the Israeli state and despite the Netanyahu government continuing to blockade Gaza.

Political analyst Hani Habeeb said Hamas previously had ruled out any negotiations with Israel. That shift hints at the group's realisation that negotiations are "the only remaining open option to return the Palestinian rights from Israeli occupation".

Other analysts suggest that this reflects a pragmatism not evident before the summer of 2014.

Hamas has attempted to reach out to Sisi's government with the ultimate goal of re-opening the Rafah crossing and ending the near-total isolation of the Gaza Strip.

It was meetings in Cairo in September 2014 that agreed a ceasefire ending the 51-day war with Israel, and Hamas leader Moussa Abu Marzouq, despite moving from Cairo to Qatar since the rise of Sisi, has conducted talks with Egyptian officials over the Rafah border.

Khalil Al-Hayya, a top Hamas political leader, recently said: "We have only love for [Eg

ypt] and we are not interfering in its internal affairs. We only ask its support, to stand beside us, and open the Rafah crossing."

However Sisi still labels the group a "terrorist organisation" and holds that its roots in the Muslim Brotherhood make it persona non grata in the region. Clearly, there is much work to be done.

Abdelsatar Qassim, a Palestinian political analyst, told Middle East Eye: “The movement is now heading toward engaging with the West, opening diplomatic communication lines with major states to convince them that the presence of the movement is as a political, and military, power on the ground."

Hamas has not, largely, been able to reach out to major EU states, many of whom still label it a "terrorist organisation", but there have been more visits with officials and party leaders in South Africa and Malaysia - mostly by the external leadership of Hamas.

But its indirect negotiations with Israel seem the only way out, given the general lack of progress on Palestinian reconciliation and peace negotiations between the PA and Israel.

They are shifting positions that mark an evolution of a group that, at the outset and to this day have met hostility from both within and without the Occupied Territories. But can that change?

Adnan Abu Amer, political analyst and dean of Al Ummah University, says Hamas has reached a level of "maturity" as it reviews its political positions to deal with the rapid changes in the region.

Others, however, do not agree. Talal Okal, a political analyst and writer for Palestinian newspaper Al Ayyam, said the group could easily pull back from its new-found flexibility.

"Unfortunately after all these years Hamas is still living under the same factional thinking and not as a comprehensive national Palestinian body.

"No one denies the implications of the choking blockade on Gaza, but Hamas is supposed to look for creative solutions which could be the foundation of the upcoming period."

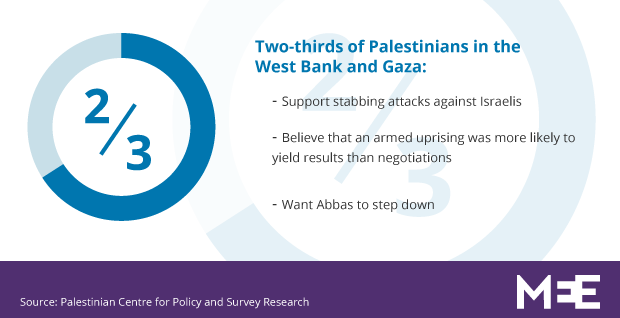

Its belligerence towards Israel, supported by the majority of Palestinians according to a recent poll, remains undoubted: The leadership was quick to call for a third intifada as attacks escalated in the Occupied West Bank this autumn, and confrontations between Israel and its armed wing, the Qassam Brigades, continue on an almost daily basis.

And when negotiations fail, the spectre of yet another war will rise. Ahmed Yousef, a top leader in Hamas, said the ongoing blockade in Gaza could easily lead a new conflict with Israel.

"Hamas does not wish for war, but the tough living conditions that people of Gaza are living could lead us there, which could come all of a sudden and without warning."

Some in Gaza appear sceptical about talk of progress. Abu Khaled, a trader in Khan Younies, admits that neither Fatah nor Hamas are able to present creative solutions to end the blockade on Gaza.

"They need to find a way out, for all, of the status quo," he says. "We have given up on official Arab support, after they showed that they won’t stand up for us, or apply real pressure to end the Israeli-Egyptian blockade," says Abu Khaled.

"We Palestinians should unite behind those who are able to liberate us, open borders and allow us access to the wider world and live in dignity."

He feels that even Hamas lacks the leverage to do the same, given the ongoing blockade. "We are left cornered, trapped between the PA and Israel; it is up to them both to let Gaza thrive in freedom and dignity."

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.