ANALYSIS: 'Reorientalism' is finding a new East

The Latin adage Ex oriente lux, ex occidente lex (“from the East, light, from the West, law”) expresses a yin-yang-like balance, signifying that both Orient and Occident are needed for harmony to exist. Imbalances between these two result in power struggles and losses - from personal to political. Such is the case of Orientalism.

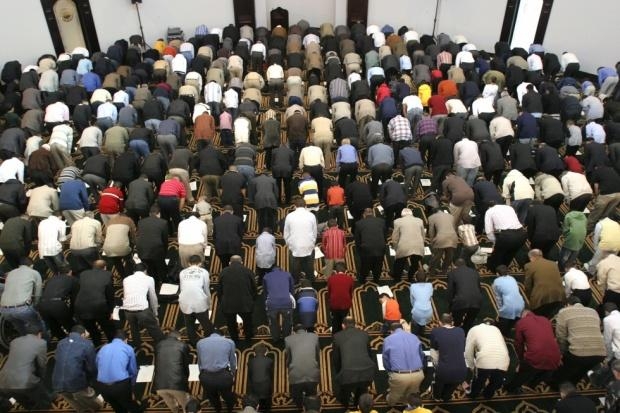

If Orientalism is the cultural misrepresentation of the West’s perception of the East, then “Reorientalism” is a much-needed, multidimensional reframing of those misperceptions. In a disoriented society that - consciously or not - pits Orient and Occident against each other, disparities and stereotypes hold firm, evidenced in mainstream media, blockbuster movies, pop culture, and patriotic politics.

Since the chain of wars that began in 2001 (Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria), we’re seeing unprecedented east-to-west migration and vast numbers of refugees - the greatest displacement of peoples since World War II. In reaction, western borders are simultaneously becoming more fluid and rigid as our world’s population shifts at a dramatic and traumatic pace. Myriad cultures, nationalities, and religions of the East are necessarily on a westward trajectory. And because the West-centric view of the Orient still tends to be overarchingly reductive and caricatural, reorienting to a clearer understanding of the peoples of the Middle East becomes ever more paramount. Rather than waiting for world governments and bureaucracies to enact change, a grassroots movement is taking place to do just that. To that end, there are pockets of communities in the West who are utilising art and culture as a means to forge social engagement, citizen diplomacy, and capacity-building.

Individuals and groups living between cultures - born of an eastern background, yet residing in a Western nation - possess the ability to initiate and sustain cross-cultural dialogue. They’re often second-generation, not newly arrived, though they help pave the way for newcomers. They’ve learned to straddle several cultures at once, and perhaps as a result have become more adept at forging friendship, collaboration, and one-to-one diplomacy. It’s happening by way of art and culture, which means the engagement between Orient and Occident is more flexible, less divisive, and in the best cases, learning to more consciously respond rather than react to the events of our day.

Part of the methodology of capacity-building includes seeking out elements of agreement between misaligned parties. To this extent, it’s through such venues as theatre, art galleries, poetry readings, book signings, performances, concerts, and food and film festivals that these meetings naturally occur. Taking the type of approach that 20th century Brazilian philosopher Paulo Friere championed, which insists that everyone has something of value to contribute, has an equalising effect, and the potential to dissolve ostracising stereotypes and the subconscious colonial mindset. This approach requires openness, creative thinking, and a certain degree of vulnerability, characteristics common in the arts.

Thus, showing up as a musician or poet or chef is less threatening or alienating than, say, showing up as a nationalist or religionist. Dimitris Mahlis of the Wahid Music project embodies this very concept, arriving in such divergent destinations as Turkey or the American south, with a passion for music and a willingness to share. This position, versus ethnic or nationalistic posturing, transcends boundaries. Wahid’s sound is essentially Ottoman, a rich collaboration of Greek, Armenian, Turkish, Jewish, and Arabic musical traditions, with a jazz aesthetic. Mahlis told MEE: “Musicians are at the vanguard, crossing borders, and reaching others who are otherwise inaccessible.” His experiences over the years repeatedly affirm this to be true, even in a post-9/11 United States where the average citizen has become more cautious or distrustful of the Middle East.

Mahlis gave an example from 2011 when playing in a world music concert at a college venue in the American south where most of the students are Caucasian and unfamiliar with other cultures. At the beginning of the show, most faces in the audience held bored expressions as they rolled their eyes at one another. By the end of the show, however, the students were completely engaged. One student passed Mahlis a note after the show, writing of his skepticism and that his attendance had been mandatory, but he’d found the music to be surprisingly inspiring. His mind had been opened, and he actually thanked Wahid for playing.

“It was rewarding in the sense that we reached somebody, showing us that music [and art] is transformative. I firmly believe that, despite our differences, fundamentally, we all want the same things. Nevertheless, there are the ‘gatekeepers,’ so to speak, who decide what’s mainstream and that’s what the majority gets. This music is not mass-marketed. So, in general, people are not readily exposed to it. But once they are, they respond, they remember. Because this music is ancient, borne from the cradle of civilisation, it’s in our DNA,” said Mahlis.

Similarly, Jordan Elgrably, founder of the Los Angeles, California-based Markaz Arts Centre, told MEE: “We live in a consumer culture; ideas are consumed as readily as products. And so we have to ask, who are the idea producers? After the fall of the Soviet Union, the West needed another bad guy. We’ve had the war on drugs, and the war on terrorism, which breeds fear in the form of Islamophobia, for instance.”

In a 2014 Pew Research Centre survey Americans were asked to rate various religions on a “feeling thermometer,” the warmer the feelings, the higher the number, 100 being the highest. HuffPo/YouGov poll conducted a similar survey in 2015. Results of both were on par with revealing that approximately half of the American population holds the least favourable view of Islam. Moreover, those expressing a negative outlook seemed not to be basing their opinions on actual knowledge of, or friendship with, Muslims. Implied is that lack of understanding and fear are the source of an “us against them” mentality.

“So, we need museums and cultural venues to counter the consumer culture, to encourage social engagement. What we [The Markaz] offer is the opposite of talking heads telling you what to think," Elgrably said. "Here we have non-Muslims meeting Muslims, starting conversations and relationships. The Markaz makes a space for cultural curiosity, which encourages empathy and compassion, and ultimately gives us tools to interact with others. Reorienting ourselves requires us to open up.”

The Markaz’s cultural programmes serve the interests of rapprochement and peer-to-peer diplomacy, welcoming people irrespective of nationality and religion in hopes of raising Western consciousness of the greater Middle East. Exemplifying this, Elgrably said, “This is why we’ll choose to showcase the work of Iranian artists. Iran is a first-world country in the Middle East, but it’s highly unlikely that the average American would think of Iran in that way.”

He continued: “We find that there are many ways to parse our identity, and that comes from understanding that we’re not composed of only one; we’re each multifaceted beings. No longer is it possible to indentify too narrowly with just one aspect of ourselves. Examples of xenophobia, parochialism and extremism are seen in the US with the Central American migrants, or with ISIS on the other side of the globe. With the concept of identity comes a need to know what it feels like to be on the inside as well as on the outside.”

To do that, we need something to help bridge this gap. Top-down policies rarely succeed in the type of one-to-one bridging that results in real human understanding. The Black Lives Matter movement parallels this premise. In a comparable way, a movement to “reorient” rises from the need to thoughtfully and creatively respond to profiling and its ill effects. Like Black Lives Matter, reorientalism is gaining momentum on the ground through a decentralised conversation via the arts that addresses our value systems.

Speaking to this, Torange Yeghiazarian, founder of Golden Thread Theatre Production in San Francisco, California, said she interprets the Orient and Occident more symbolically than geographically: “It’s more about value systems. For example, nothing is more oriental than China in terms of its location, yet in terms of its value system, China’s more recently adopted values are more in alignment with Western Europe and the US. When I talk about reorienting, I think of what’s symbolically eastern, like warmth (as from the sun), community and generosity. These are the values that I live by and upon which the theatre company is based.

"This informs my sense of community, sharing, dialogue and inquiry. In the Golden Thread community, there is mutual investment in one another’s lives, and continued questioning of our own perceptions as well as that of others. The dynamics are ever-changing. Likewise, the idea of reorienting is dynamic and shifting and moving toward a more inclusive way of living rather than supporting only one group at the expense of another.”

Yeghiazarian said Golden Thread began in 1996, driven by a need for self-expression and a space on the American stage for performers of the Middle East. "And now almost 20 years later, Middle Eastern-American theatre is a recognisable genre. Important stories are being told by many voices of the Middle East, and the poignancy of theatre is that it’s not a lecture.

"Theatre confesses personal, human stories; and that can be scary because to watch someone else’s story in an intimate theatre is to be drawn in and to begin to understand what another person is going through. Theatre is able to highlight our commonalities, and we realise that we are all vulnerable.”

Art is not compartmentalised or from a source outside the self. Artistic expression - whether visual or performance, music, dance, literature, cuisine - is part of a democratic, socially just society, and as such, has the power to transform itself into a form of cross-cultural diplomacy. Art has the ability to engage polarised cultures in ways that sound bites or governmental policies cannot. The sharing of art and culture has the power to educate, inspire meaningful encounters, cultivate common ground, and envision possibilities that do not yet exist.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.