ANALYSIS: Is a rising Iran an economic opportunity or risk for Turkey?

ISTANBUL, Turkey - The return of Iran from the international wilderness after a nuclear agreement that will see the lifting of sanctions could provide an economic boost for Turkey in the short term as trade and business soar. Turkey is already Iran’s fourth trade partner with opportunities from energy to automobiles aplenty.

However, it could also present a threat in the long term as these two traditional regional powers and rivals compete for foreign investment, say analysts.

After more than a decade of negotiating, Iran and the P5+1 group of international powers - the UN Security Council’s five permanent members plus Germany - reached an agreement on 14 July that curbs Tehran’s nuclear activities in return for the lifting of crippling sanctions that have all but cut off the country from the international arena.

According to Kerem Alkin, a macroeconomist and professor at Istanbul Medipol University, Turkey stands to gain from the lifting of sanctions on Iran but needs to keep on its toes about not losing out to competitors and securing business in Iran in the short term, while also making sure that a resurgent Iran does not begin to challenge Turkey in industrial fields where both countries have an interest.

“Good opportunities will open up for Turkish businesses, particularly in the service and retail sectors, but we can’t afford laxity since, even during the term of [former Iranian president Mahmoud] Ahmadinejad at the height of sanctions, flights from Istanbul to Tehran were packed with Westerners seeking out future business opportunities there,” Alkin told Middle East Eye.

Umit Erol, a professor and head of the Business Administration faculty at Istanbul’s Bahcesehir University, said Turkey will benefit from a trade upsurge in the short term but the longer term outlook is more difficult to assess as a lot will rely on the political dimension of ties between the two countries.

“There will be an increase in frontier trade, but whether the positives of Iran’s return to the fold outweigh the negatives in economic terms for Turkey remains to be seen,” Erol told MEE.

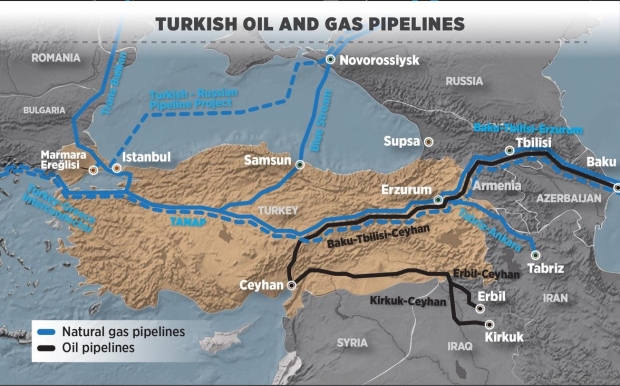

Natural-gas pipeline

The opening of an untapped Iranian market that possesses an educated young workforce, administrative infrastructure and a stock market means Turkey should endeavour to put itself in a prime position to forge ahead in the race between Western countries vying to establish themselves in the Iranian marketplace.

Erol said there is a big market in Iran in consumer electronics and other similar areas that Turkish businesses can benefit from by investing in them, but stressed that Turkish companies might find it difficult to hold out against Western companies for long.

As ties warn, the issue of Iran’s abundant energy reserves – it hold the world’s fourth-largest oil reserves and second-largest natural gas reserves – will also dominate discussions. Both are of vital importance to energy-hungry Turkey, which is trying to position itself as an energy hub and transit route for hydrocarbons from East to West.

The one area Turkey which really stands to benefit, according to Erol, is a proposed natural-gas pipeline that would start in Turkmenistan, pass through Iran and Anatolia and extend to Western Europe.

“This natural gas pipeline project will now become a lot easier to implement and will bring considerable gains for Turkey,” said Erol.

The political risk of the pipeline has increased significantly in recent days with an explosion rocking an existing pipeline in the eastern Turkish province of Agri, according to the Turkish Energy and Natural Resources Ministry.

The suspected sabotage attack took place in the Dogubeyazit district, about 15 kilometres from the border with Iran, the Anadolu news agency quoted Turkish Energy Minister Taner Yildiz as saying in a statement late on Monday.

No one has immediately claimed responsibility for the blast but local media reported that the outlawed Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) is behind the attack.

Despite this, analysts believe that

Turkey’s stance of usually not antagonising Iran and maintaining a cordial relationship with Tehran by often supporting its positions in the international arena - except in the case of the Syrian conflict - could give it an edge in forming business ties with Iran’s mostly state-controlled businesses regardless of any uptick in tensions with the PKK.

Alkin believes that Turkey and Iran should aim to at least double their present trade volume of about $14bn, which represents a mere 1.25 percent of both countries’ combined national incomes. (The trade balance is in Iran’s favour as a result of its oil and gas exports to Turkey.)

“Both countries need to ensure that their differences over Syria don’t reflect on their relations as a whole, and Iran should not forget the international support it received from Turkey during difficult times,” said Alkin.

“In fact, a more robust trade relationship could mean that Turkey and Iran will look to cooperate more to face the threat posed by the Kurdistan Workers’ Party and the Islamic State group.”

Competing for investment

In the long term though, the two countries might find themselves competing for foreign direct investment, given their demographic and geographic similarities.

“Look at the industrial sector of cement production and other construction materials for example. Turkey has already lost ground to Iran when it comes to such exports in nearby markets such as Iraq and Egypt,” said Alkin. “The quality of their [Iran’s] product might not be up to scratch but their prices are very competitive.”

According to Alkin, Turkey needs to work hard to present a picture of economic and political stability to foreign investors because otherwise, in five to 10 years, they might start looking to Iran as an alternative place to invest.

He pointed to the automotive assembly industry. “Before the sanctions, Iran had invested heavily and was a major regional player in this sector, and there is no reason for it not to become so again and thus attract foreign direct investment in that area,” he said.

Erol agrees: “The automotive industry in particular is an area where Western automotive firms will seriously consider Iran as a place to invest to both tap into local demand and seek out neighbouring markets.”

Regional trade rivals

In regional terms, at least until recently, Turkey appears to have a distinct edge over Iran’s other major regional trade partner, the United Arab Emirates. The UAE, despite making it easier bureaucratically for Iran to do business, is ideologically at odds with Tehran and toes the line of Iran’s arch political foe, Saudi Arabia.

For Alkin, logistics are also a determining factor when it comes to Iran choosing trade partners.

“It is only 800 kilometres from Iran’s industrialized north-western region to the port of Trabzon in Turkey, whereas it is more than 1,400 kilometres to its port of Bandar Abbas on the Persian Gulf,” he said.

“Both countries need to look at improving logistics and at removing bureaucratic and tax-related barriers to enable better use of such transport links.”

Erol, however, doubts whether Turkey has an edge in this regard, citing the Turkish government’s Sunni-focused regional foreign policy of recent years, and adding that if Turkey doesn’t change its policies in the Middle East it certainly stands to lose out with regard to Iran’s re-entry to the fold.

“Turkish foreign policy is a shambles right now, and if Turkey doesn’t change its policy of trying to act as the guardian of Sunni interests in the region it will put it on a collision course with Iran. This has been a point of contention between the countries since the 17th century,” said Erol.

‘Dubai never again’

Hamid Kheirollahi, an Iranian businessman based in Turkey since 2011 who was previously based in Dubai, said that despite the bureaucratic process being more complex and haphazard in Turkey, it is much better to do business with Turkey than it is to do so with the UAE.

“Although the cost of doing business rose exponentially for me after moving to Turkey, I will continue to operate from here because they allowed me to work during the tough times,” said Kheirollahi in reference to sanctions.

He said he knows plenty of Iranian business people like himself who moved their businesses to Turkey after sanctions were tightened against Iranian nationals in 2010 and feels that he was betrayed and cheated in the UAE.

Kheirollahi says he plans to continue operating from Turkey once sanctions are lifted and sees it as an opportunity to expand his business ventures by including Iranian-Turkish trade.

“I am really happy here. My family is happy here. I see no reason to move. I certainly would never return to Dubai even if they provided me with a load of incentives.”

It is clear that regional powerhouses Turkey and Iran will have to be alert not to squander this opportunity in their quest for regional domination and make utmost use of these changed circumstances to benefit economically, concluded both Alkin and Erol.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.