ANALYSIS: Tunisia to crack down after beach attack

SOUSSE, Tunisia - Nobody ever imagined that the beach at Port al-Kantaoui could look like this. Police tape fluttering in the breeze. Dazed tourists making their way across the sand to pay their respects at the site where, a day previously, Seifeddine Rezgui gunned down 38 holidaymakers. Set against an azure sea and the blue skies of a balmy June day, the beach outside Sousse became a killing ground that borders on the perverse.

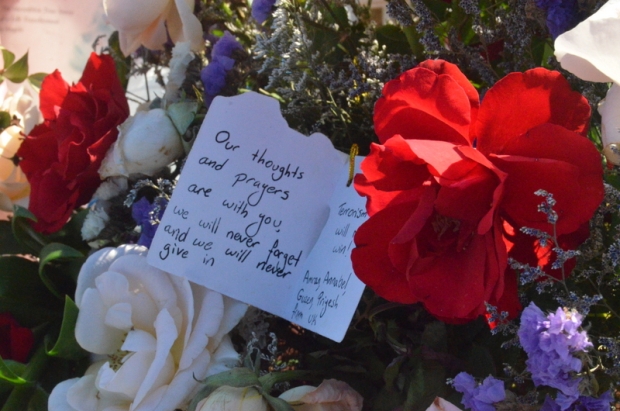

The horror of Friday’s slaughter, splashed on front pages around the world, has given way to mourning, not least in Britain, the country that lost the most lives in the massacre.

Sorrow and incomprehension have merged into a search for an explanation, a need to understand what led Rezgui to evade security forces and commit a heinous crime, just three months after a similar attack at the Bardo Museum in the capital Tunis.

The day after the beach attack, Prime Minister Habib Essid announced a security clampdown. Army reservists, he said, would now guard popular archaeological sites and the Zones Touristiques, purpose-built tourist areas similar to Sousse, which line Tunisia’s white-sanded coast.

The main focus of the clampdown, however, were 80 mosques Essid accused of “spreading venom” in Tunisia’s secular heartlands. The mosques would be closed, he said, by the end of the week.

That mosques play a role in radicalising disaffected men from Tunisia’s impoverished suburbs and remote towns like Gaafour, Seifeddine Rezgui’s hometown, is indisputable.

Proof resounds in the familiar stories about quiet, polite sons who started visiting mosques and growing their beards, before leaving to fight in Syria and Iraq.

Fadhel Achour is president of Tunisia’s National Union of Imans and a former imam at the historic Zitouna Mosque in Tunis. Like many others, he was forced out of the mosque by a hard-line preacher shortly after the 2011 revolution against long-time President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali.

“Every day a mosque will hold around two thousand people of different ages, background and views. They go there with their defences down. The imam has authority. Anything he says comes from God,” Achour told Middle East Eye.

It’s a type of authority the recruiters for militant groups in Tunisia are quick to seize upon.

“These people (the imans) aren’t stupid or naïve, their arguments are good. They explain everything - the bad economy, the lack of social values - through the absence of religion in Tunisia,” he said.

The imams tailor their recruitment according to the specific individual, according to Achour.

“It’s as if they stalk their victim. They tackle their worst fears, if they’re looking for a job, if they lack faith, whatever, they’ll use it. They’ll present themselves in whatever light will best convince their potential recruit,” he said.

For young men living in Gaafour and hundreds of other remote Tunisian towns, the mosque’s radical messages help them make sense of a lifetime of poverty and crime.

Three thousand Tunisians are currently fighting in Syria and Iraq and a further 12,940 have been prevented from leaving Tunisia for "combat zones," according to Tunisia’s Interior Ministry.

Even if the majority of those were recruited in mosques, closing the religious institutions will not help, according to Mohamed Iqbel Ben Rejeb, the president of the Rescue Association for Tunisians Trapped Abroad, an organisation that mediates between the families of Tunisia’s foreign fighters and the authorities.

“If we close mosques we’re sending a message to these young men that the government is fighting religion in the same way Ben Ali did,” said Rejeb. “Instead, we should be controlling these mosques… making sure they have imams well versed in the Quran and known for their competence.”

Fadhel Achour has few doubts about the impact of mosque closures: “If you close their mosques, they will just go to fight jihad in Syria, others will go to the Chaambi mountains (the stronghold of Tunisia’s Al Qaeda-linked groups) and fight the government.”

While some of Tunisia’s mosques have become breeding grounds for armed militancy, others are important places of worship, particularly for Tunisia’s conservative Salafist community, a group that already feels alienated by a secular government.

“They’re closing mosques on the basis of the broadest of allegations,” Amna Guellali, Human Rights Watch’s Tunisian director, told Middle East Eye before the beach attack.

“Similarly, Salafists and their imams are finding themselves increasingly open to detention and arrest on the flimsiest of suspicions, which is only alienating them further.”

As Tunisia tightens its grip on mosques, uncomfortable echoes of an autocratic past are sounding through the prayer halls of Tunisia.

“We’re going back to the kind of state-sponsored religion we saw with Ben Ali, with centrally generated sermons and restricted access to the mosques outside of prayer time,” said Guellali.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.