ANALYSIS: Turkey's HDP seeking a stronger parliamentary presence

The largest Kurdish political organisation of Turkey, the Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP) has decided to enter the upcoming June elections. In what is considered to be a surprising move, the party leadership now wants to challenge the ten percent election threshold that is preventing minor parties from taking parliamentary seats.

Implemented during the military rule of early 1980s, the aim of the threshold was to increase political stability by preventing the formation of fragile coalition governments. As opposed to the Kurdish political movement's previous methods to gain parliamentary seats as independent candidates and then forming their party groups in the parliament, there are serious doubts about the party's capability to surpass the election threshold.

"The threshold is not an obstacle for us. We will overcome this, as we have triumphed over similar barriers in Kobane," Selahattin Demirtas, the co-chair of HDP said last week.

Although Demirtas' performance during the last presidential elections of August 2014 demonstrated HDP's rising popularity as he managed to secure 9.76 percent of the vote, the party now runs the risk of being sidelined if it cannot succeed in its quest to get into the parliament.

The threshold - the highest percentage in the democratic world - inhibited the parliamentary representation of sizeable populations for years, especially Kurdish populations.

The most dramatic example of this was when around forty-five percent of the electorate could not be represented after the 2002 elections, when only the Justice and Development Party (AKP/AK Party) and the Republican People's Party (CHP) were able to enter parliament.

Though historically the threshold does not target the Kurdish political movement, per se, the idea of preventing the formation of political parties on the basis of region and ethnicity inadvertently affected Kurdish representation in the parliament.

Fed up with the political prosecutions of the 1990s and early 2000s, Kurds managed to enter parliament in the last two general elections in 2007 and 2011 by securing votes for independent candidates in their stronghold of southeastern Turkey.

Since the end of military rule of the early 1980s, once elected, many political parties promised either total eradication or significant lowering of the election threshold. However, neither AKP, nor its predecessors kept their promises.

Reasons behind the HDP decision

Encouraged with Demirtas' relative success during the presidential elections of last year, HDP has been aiming to transform itself from an ethnic- and region-oriented political party into an all-embracing centre-left party for over a year now.

For many, including the party's leadership, the dissolution of the Peace and Democracy Party (BDP) -the predecessor of HDP - and its amalgamation with HDP is a reflection of the Kurdish political movement's vision to become a nationwide advocate for underrepresented masses who are fed up with the current government as well as opposition parties.

Like most of the protesting youth during the Gezi Park protests of 2013, those masses do not feel close to any of the four main parties in Turkey. HDP is aiming to present itself as an alternative for them.

However, serious doubts about the party's real leadership breed suspicions. Because it is allegedly taking orders from the outlawed Kurdish armed group PKK's jailed leader, Abdullah Ocalan, many Turks still do not fully believe in the party's leftist and all-embracing discourse.

In the first days of the HDP, Kurdish politician Orhan Miroglu did not deny this connection and claimed that the formation of a nationwide party was the idea of Ocalan. "He [Ocalan] is the mastermind of this new party, which is designed to be an umbrella political party."

According to HDP MP,Idris Baluken, HDP currently possesses 10.5 percent of the votes, a share that would allow the HDP to send around 55 MPs to parliament. This number would obviously be a historical high, as the Kurdish political movement's biggest success was to get 35 seats in the 2011 elections. After the elections, independent members have formed the BDP group in parliament.

This scenario also raises the question of who will lose their seats. Considering HDP's traditional votes in south-eastern Turkey, the biggest loser would obviously be the AKP, as two other opposition parties virtually do not have a presence in that region.

For polling experts like Ozer Sencar, the director of the public survey agency, Metropoll, the AKP will be the biggest loser if HDP exceeds the threshold. As the AKP is the only rival party in that region, more than 20 of its seats would be reassigned to the new HDP members, potentially reducing the AKP seats to as low as 280.

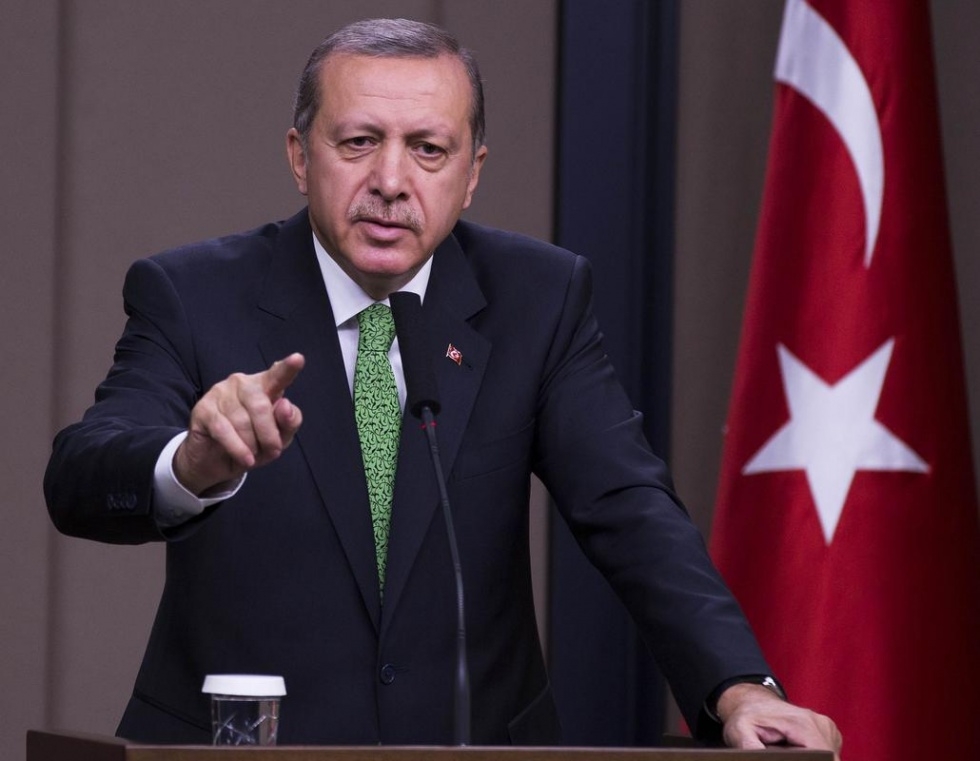

The government party currently possesses 312 seats and is hoping to increase it to at least 330, in order to freely work on a brand new constitution granting President Recep Tayyip Erdogan the executive powers that he currently does not possess. The new constitution also aims to solve the decades-old Kurdish issue by redefining key notions like citizenship and ethnic identity.

The real chance for success

Since the party's decision, both AKP and HDP members have increasingly been speculating on the possible outcome. "I do not believe that they [HDP] could get more than six to seven percent," Deputy Prime Minister Yalcin Akdogan said last week.

Referring to HDP's objective of attracting different left-leaning segments of society, Akdogan further said: "They have their own contradictions, including marginal leftist factions and organisations. They could only seek temporary votes from other parties."

However, HDP members seem to be adamant about their decision. "We have to reach out to all four corners of Turkey […] You have to make way to democratic politics […] If we cannot exceed the threshold, it is up to the government to deal with it," Sirri Sakik, HDP member and mayor of Agri argued.

It is too early to assess the end result of HDP's high-stakes game, but the party discourse appears to be based on rather negative campaigning. On one hand, some HDP members emphasise doom scenarios if the party fails to surpass the threshold. On the other hand, they seek votes from the disillusioned electorate.

Mithat Sancar, a law professor at Ankara University and a long-time observer of the Kurdish political movement, says HDP believes in its own potential and has to defend its decision. He does not think that the party's attitude is a negative one, but rather a warning sign.

"Anyone who thinks that HDP should exceed the threshold should go and vote for them," Sancar told Middle East Eye. "I do not think that HDP's discourse is dismissive or consists of blackmail."

According to the prime minister's advisor, Etyen Mahcupyan, the only way for the HDP to secure more than 10 percent is actually in the hands of PKK's jailed leader, Abdullah Ocalan.

"If PKK lays downs its arms upon a call from Ocalan and if the leadership in Qandil mountains grasp this idea at the next stage of the 'resolution process', then HDP's chances would increase," Mahcupyan recently said at a conference in the Iraqi Kurdistan city of Erbil.

However, if HDP cannot get into parliament, the outcome could be beyond imagination. Demirtas reiterates that the loser of that outcome would be the AKP, not themselves, as they are determined to press ahead with their own agenda in the aftermath. This could include consolidating the power of local administrations in the Kurdish southeast.

According to the research director of Al-Sharq Forum, Galip Dalay, HDP is pursuing two simultaneous strategies: to "expand" and transform into a nationwide left party, and "deepen" (establishing deeper connections with Kurds who do not follow the BDP-HDP line) by becoming more appealing to the Kurdish populated regions.

"If they fail at the elections, HDP would probably abandon the expansion strategy and focus on deepening," Dalay told MEE. "This could lead them to pursue more radical strategies, including increasing efforts for democratic autonomy."

Another outcome is highly speculative, yet increasingly discussed in political circles. The speculation is that PKK's jailed leader and President Erdogan struck a hidden deal to keep the HDP out of parliament. This way, AKP would gain the necessary number of seats in parliament to be able to unilaterally change the constitution or call for a referendum. In return, according to this line of thinking, with the new executive powers that are to be bestowed upon Erdogan after the introduction of a new constitution, he promises a more decentralised Turkey, even a federal system where Kurds could enjoy the freedoms that they have demanded for years.

Dalay, however, believes that the Kurdish political movement is mature enough to not bite at such speculative bait. "I believe that HDP was a nationwide project since the first day of its establishment, and entering the election as a party has been one of the main objectives," he said.

For Sancar, this scenario is baseless and against logic. "If HDP was planning to accept such a deal, it would not have launched a big election campaign in the first place," he argued. "The problem is that if HDP is left out, the AKP cannot write and approve a brand new constitution without facing the consequences on legitimacy."

What the outcome of this speculative scenario would be remains to be seen, but for many observers, radicalisation of both sides would be one of them.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.