ANALYSIS: US Republican waits in the wings to scuttle Iran nuclear deal

On 24 November, a landmark deal exchanging of US sanctions relief for further Iranian nuclear transparency might be sealed, opening the door for greater dialogue between the intractable enemies.

Short of that, the deadline will almost certainly be extended once again, putting future diplomacy at the mercy of the US Congress which, thanks to the November mid-terms will soon be dominated by Iran hawks, many of whom appear to be acting only to deny Obama any successes, anywhere, anyhow.

Analysts both in Iran and in the West believe that if no deal is done and the deadline is extended – as was widely rumoured had already happened earlier this week - Iran will walk away from the negotiations unless some confidence-building progress is “locked in” in a partial deal on 24 November.

“Postponement only becomes significant and unsustainable if it extends the negotiation into the new congressional session [February 2015],” said Professor Farideh Farhi, an Iran scholar formerly at Tehran University and now at the University of Hawaii.

“This is why I do not think the Iranian team will accept such delays. This doesn't mean that I am foreseeing a breakdown; rather that a mere delay under the same terms will be difficult to sustain in Washington and Tehran.”

The concern is widespread. “Putting off a deal yet again would, in fact, produce a perilous slide back towards crisis and confrontation,” Gary Sick who served on the National Security Council under Presidents Ford, Carter, and Reagan and was the principal White House aide for Iran during the Iranian Revolution and the hostage crisis told Politico.

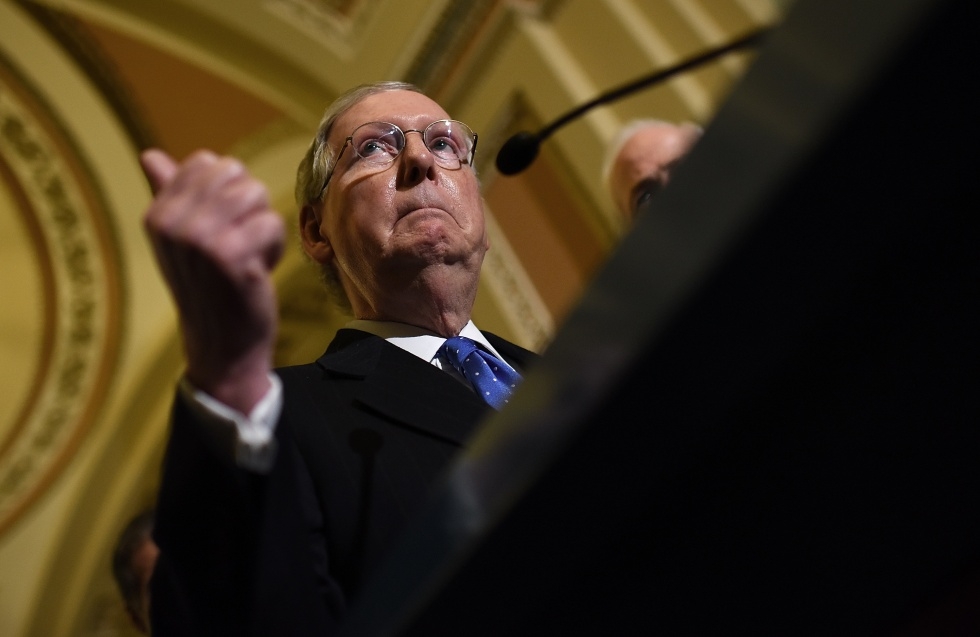

Fresh from their mid-term win more two weeks ago and wary of the upcoming deadline for the nuclear negotiations, Republicans have snapped into action on Capitol Hill, in what the Iranian press termed the "Shadow of elephants on the negotiation table" (a reference to the Republican Party symbol).

On 8 November Republican Senator Lindsey Graham told a pro-Israel advocacy group that he would “kill” an agreement that he considered a “bad deal”. Days later he asked senators for permission to hold a vote on a new bill that would empower Congress to veto a deal or place new sanctions on Iran – it also pledged US military assistance to Israel if it chose to strike Iran.

If Congress had not shot down the proposed vote, Graham would most likely have succeeded in effectively killing the deal before it had a chance to be born.

However, most analysts believe that the proposal was really just theatre and a way for the more hardline elements of the Republican Party (also known as the GOP) to look tough and let off steam. The day before Graham took to the Senate floor, chairman-in-waiting of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee (SFRC) Republican Senator Bob Corker - whose name appeared alongside Graham’s on the proposal - told several reporters that the GOP would only decide after the November deadline and in the event of an extension to the talks on whether to slap new sanctions on Iran.

Even Democratic Senator Robert Menendez, the current SFRC chairman, and Republican Congressman Mark Kirk - who have together been behind several attempts to place new sanctions on Iran during the talks, issued a tough sounding statement that essentially said the GOP would hold fire before the deadline.

But the Republicans will exercise more of a bite when it comes to the implementation of any deal, partly because many in their ranks are influenced by the Israeli right, which wants to scupper a deal that does not involve total Iranian capitulation.

Israel is loath to see a deal that preserves Iran’s enrichment capacity, which will almost certainly remain intact (Iran’s hypothetical nuclear ‘breakout’ ability will instead likely be limited by a fuel transfer to Russia, which has also agreed to build eight reactors in Iran).

As part of a prospective deal, President Barack Obama can use his executive power to both veto new sanctions proposed by a GOP-majority Congress after a deal and remove sanctions by executive order for 120 days. He can also quickly lift sanctions negotiated with EU states to cut Iran’s crude exports and some smaller sanctions that were placed by the executive in the first place - for example Executive Order 13645, which imposes sanctions on companies trading in Iranian currency or supplying Iran’s car industry.

Yet at some point between 24 November and the day Obama leaves office in January 2017, he will need Congress to permanently lift key sanctions as part of any deal with Iran.

Iran may reluctantly accept an agreement whereby sanctions (for example those under 2012’s Comprehensive Iran Sanctions Act or 1996’s Iran and Libya Sanctions Act that have dried up Iranian credit lines and trading partners) are only lifted towards the end of Obama’s presidency. But the Iranian elites will not commit to their side of the deal if they believes Congress will just hobble the US administration’s ability to push through a deal.

"The Islamic Republic of Iran will not accept the remaining of even one sanction in the comprehensive nuclear agreement," Deputy Foreign Minister Seyed Abbas Aragchi said on 25 October.

In the eyes of many US administration officials, delaying the bulk of sanctions relief will also advantage the US as it can show Congress that Iran has fulfilled its obligations under a comprehensive agreement which will encourage their compliance. But compliance will be largely determined by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). The IAEA’s biggest outstanding case file on Iran is called “possible military dimensions”, which, according to Iran, is based on fabricated evidence planted for political ends and on which former IAEA weapons inspectors have cast doubt.

If Iran believes sanctions relief will only come if it resolves irresolvable IAEA case files, the chances of deal on 24 November become even more unlikely.

“I really fear that due to the recent GOP win we are now going to have a situation where bad action will not be held up,” said Jamal Abdi, policy director for the National Iranian American Council. “Instead we’ll see bad measures pass and get vetoed by the president, which will create a lot of tension between the White House and Congress.”

This could make an unprecedentedly toxic relationship between the US legislature and its executive even more poisonous, and just before Obama needs Congress most to sign away the sanctions, or giving the president the legal authority to do so himself.

“The notion that you’re going to – within the next two years – get to a point when the two sides are willing to compromise and pass legislation that gives the president the authority to lift sanctions becomes more and more remote,” said Abdi.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.