The Armenian genocide explained

The issue of the mass killings of Armenians and other Christian minorities in 1915 in what is now Turkey has long provoked anger, sadness and intense fighting - often literally - around the world.

Armenians and international scholars have branded the killing of as many as 1.5 million ethnic Armenians across the Anatolian peninsula a genocide, initiated by the Young Turks' administration, an assessment that Turkey has long denied, arguing the death toll was much lower.

Recognition of the Armenian genocide has generally been influenced by geopolitics - historical allies of Turkey such as the UK, Israel and Azerbaijan have long refused to recognise the killings as genocide, while countries more hostile to Turkey, or with large Armenian communities, such as France, Greece and Lebanon, have acknowledged it.

For a long time, the US was among those that resisted the "genocide" label. However, the new administration of President Joe Biden has announced its intention to recognise the killings as an act of genocide, provoking a diplomatic spat with Turkey.

As Biden prepares to speak with his counterpart Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan on Saturday, Middle East Eye takes a look at the history and legacy of one of the most tragic and controversial events of the 20th century.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The run-up to the genocide

For centuries, the multi-faith Ottoman Empire had organised its various minorities under the "millet" system, which effectively gave a degree of self-governance to different communities, including the Armenians.

In the 19th century, attempts by the Ottoman Empire to modernise and secularise its institutions led to a change in this relationship and the millet system gradually collapsed, leading to greater centralisation of the Ottoman state.

The changing relationship between the Ottoman state and its subjects, as well as the spread of new communication technologies, led to the rise of nationalism and a desire for self-determination among religious communities, and increased tensions with their Muslim-Turkish rulers and neighbours.

'What on earth do you want? The question is settled. There are no more Armenians'

- Talaat Pasha, Young Turks

The first brutal harbinger of what was to come occured in 1894, during the rule of Sultan Abdulhamid II who advocated pan-Islamic ideals. That year, with rising agitation for reform by Armenian political organisations, massacres broke out across Anatolia, eventually leading to the deaths of between 80,000 and 300,000 Armenians and 25,000 Assyrians over three years.

Though Abdulhamid II would deny direct involvement in the killings, internationally he was blamed for the deaths - referred to by the New York Times in 1895 as an "Armenian Holocaust" - and they would go down in history as the Hamidian Massacres, while he would earn the epithet "Red Sultan".

Tensions continued to ebb and flow, despite optimism among some Armenian activists that the rise to power of the Committee of Union and Progress (known popularly as the Young Turks) in 1908 and their forcing of Abdulhamid to return to constitutional rule would see their prospects improve.

While the CUP, an organisation that sought to reform the Ottoman Empire through liberal and secular values, initially stressed the non-sectarian nature of the empire, they would soon be caught up in a wave of pan-Turkic and pan-Islamic sentiment.

The genocide

The CUP brought the Ottoman Empire into the First World War on the side of Germany and the axis powers against France, Britain and Russia.

Russia had long coveted territory in Anatolia - with the Ottomans doing likewise in the Caucasus - and reached out to Armenians in eastern Anatolia, arguing that as fellow Christians they would fare better under Russian rule. Some Armenians reciprocated and defected to join the Russian ranks.

Increasingly, the CUP and local governors began to view Armenians as a fifth column who posed an existential threat to their rule.

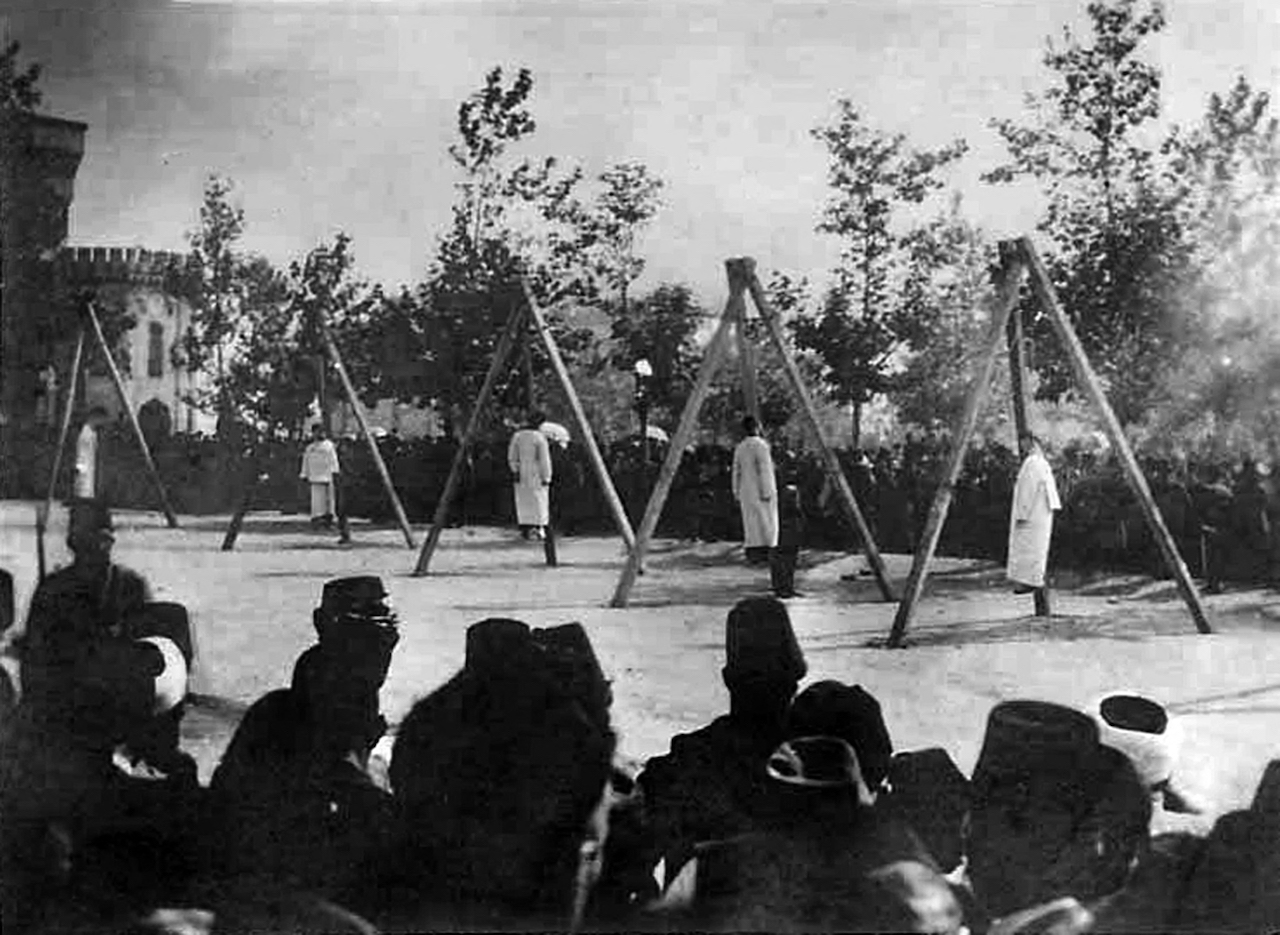

Though massacres of Armenians in Anatolia had already taken place for months before, historians generally recognise 23–24 April 1915 as the beginning of the genocide.

Talaat Pasha, one of the "three Pashas" that made up the leadership of the CUP, ordered the mass arrest of hundreds of Armenian intellectuals, community leaders, religious figures and politicians, most of whom would be tortured and killed. He then ordered the closure of all Armenian organisations in the country.

On 26 May 1915, Talaat's "Deportation Law" was approved by the government, allowing for the deportation of the Armenians of eastern Anatolia to an undisclosed location away from the frontlines with Russia.

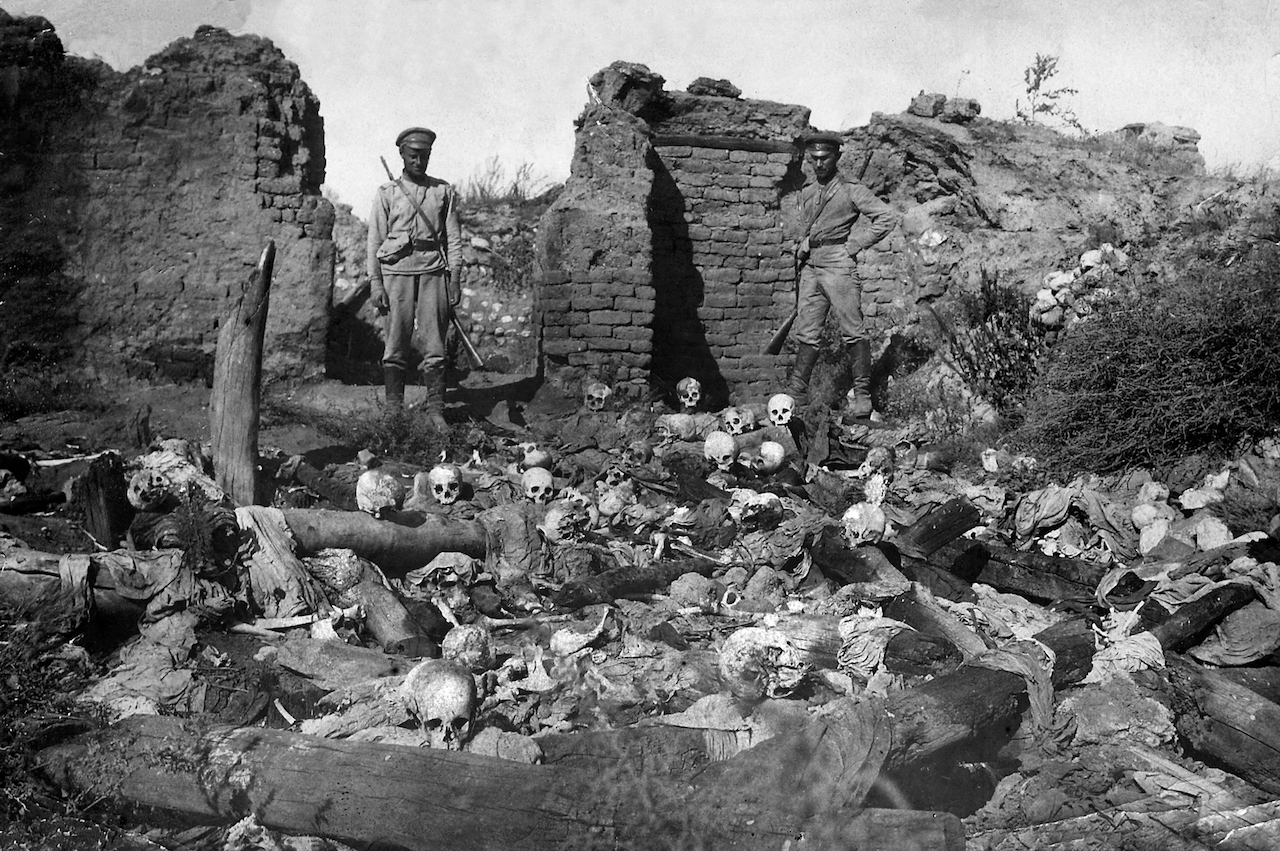

Following this, Armenians across Anatolia were either slaughtered or deported en masse to the Syrian desert in long marches by foot where the chances of survival were minimal. Tens of thousands were left to die on the roadsides after being denied food and water or contracting disease.

Numerous witnesses have over the years testified to the violence that was meted out against the Armenians across Anatolia by paramilitary groups, the army, police and armed gangs.

"From the first days of our journey, we met many groups of Armenians. The Turkish armed guards and gendarmes drove them (on foot) towards death and perdition. First, it made us very surprised, but little by little we got used to it and we even did not look at them, and indeed it was hard to look at them," wrote Mohammad-Ali Jamalzadeh, an Iranian writer, in 1915.

"By the hit of lashes and weapons, they drove forward hundreds of weeping weak and on foot Armenian women and men with their children. Young men weren't seen among the people, because all the young men were sent to the battlefields or were killed for precaution."

Eitan Belkind, a British spy and member of the Ottoman army, recounted a particularly gruesome incident at the hands of Ottoman soldiers.

"After a three-day ride I reached the heart of Mesopotamia where I was a witness to a terrible tragedy... the Circassian soldiers ordered the Armenians to gather thorns and thistles and to pile them into a tall pyramid... afterwards they tied all of the Armenians who were there, almost five thousand souls, hand to hand, encircled them like a ring around the pile of thistles and thorns and set it afire in a blaze which rose up to heaven together with the screams of the wretched people who were burned to death by the fire... Two days later I returned to this place and saw the charred bodies of thousands of human beings," he wrote.

Though it is hard to confirm an exact figure, the Encyclopedia Britannica estimated there were around 1,750,000 Armenians in the Ottoman Empire prior to 1915.

Today, the population of Armenians in Turkey is thought to be around 70,000.

What was the intent?

The question of intent has been raised numerous times - was the intent of the CUP to wipe out Anatolia's Armenians?

Taner Akcam, arguably the most prominent Turkish scholar of the genocide, has said correspondence unearthed from Ottoman archives makes clear the intent of the CUP and local officials to "annihilate" the Armenians.

He cited one letter from Bahaeddin Sakir, a founding member of the CUP, which stated that the organisation had "decided to annihilate all of Armenians living within Turkey, not to allow a single one to remain, and has given the government broad authority in this regard”.

He also added that other documents indicated that, before the CUP had even issued its own policy, local governors in eastern Anatolia had issued orders for the "extermination" of Armenians.

“In their communications - both with Istanbul and with one another - the governors did not see the need to use vague language or euphemisms in referring to the annihilation of the Armenians, but spoke of it openly, even offering a number of tangible ideas regarding how such an extermination could or should be carried out,” said Akcam.

A number of quotes from Talaat Pasha, often referred to as the architect of the genocide, would also seem to shine light on the matter.

In an interview with the Berliner Tagblatt newspaper in May 1915, he said there could be no distinction of innocence or guilt among Armenians.

"We have been blamed for not making a distinction between guilty and innocent Armenians. [To do so] was impossible. Because of the nature of things, one who was still innocent today could be guilty tomorrow. The concern for the safety of Turkey simply had to silence all other concerns. Our actions were determined by national and historical necessity," he said.

During a conversation with a German embassy official in 1915, Talaat Pasha was even more frank about the outcome of his plan.

"Turkey is taking advantage of the war in order to thoroughly liquidate its internal foes, i.e., the indigenous Christians, without being thereby disturbed by foreign intervention," he said.

"What on earth do you want? The question is settled. There are no more Armenians."

Aftermath

The killings provoked outrage across the globe, particularly in the Christian-majority lands of Europe and America.

Russia, Britain and France - the Ottoman Empire's First World War enemies - in 1915 issued a condemnation of the killings, promising to "hold personally responsible for those crimes all members of the Ottoman government, as well as those of its agents who will be found implicated in similar massacres."

In practice, however, the allied powers failed to take much real action against the perpetrators, as geopolitical interests took precedent following the defeat of the Ottoman forces and the occupation of the Anatolian peninsula.

Many of those fleeing or driven out of Anatolia to the east found protection in Arab lands.

The Sharif of Mecca, then the figurehead of the Arab anti-Ottoman uprisings, issued an edict in 1917 to Muslims to "protect and to take good care of everyone from the Jacobite Armenian community living in your territories and frontiers and among your tribes; to help them in all of their affairs and defend them as you would defend yourselves, your properties and children, and provide everything they might need whether they are settled or moving from place to place."

Large Armenian communities still exist in Syria and Lebanon, the descendants of refugees from the genocide.

One of those to publicly condemn the killings and directly lay the blame on the CUP was Mustafa Kemal (later known as Ataturk), founder of the Republic of Turkey. Quoted in the Los Angeles examiner in 1926, he said that the remnants of the party should "have been made to account for the lives of millions of our Christian subjects who were ruthlessly driven en masse, from their homes and massacred."

His comments came only three years after he agreed a population swap with Greece that largely emptied Anatolia of the majority of its remaining Christian population.

Talaat Pasha would later be shot dead by an Armenian assassin in Berlin in 1921, after having fled the Ottoman Empire.

In the decades following the foundation of the republic, there would be continuing calls from Armenians in the diaspora and in what is now Armenia (then part of the Soviet Union) for Turkey to recognise the genocide. A smaller number also argued that parts of what now make up eastern Turkey that were once inhabited by Armenians should be incorporated into part of a greater Armenian state.

'The road to peace and democracy in the Middle East passes through the recognition of the Armenian genocide'

- Taner Akcam, academic

The Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia (ASALA), founded in 1975, took matters further and began carrying out attacks on Turkish targets, demanding the country atone for the genocide.

In 1997, the International Association of Genocide Scholars unanimously declared the killings to be a genocide, reaffirming that the "mass murder of over a million Armenians in Turkey in 1915 is a case of genocide which conforms to the statutes of the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide" adding that the group also condemned "the denial of the Armenian Genocide by the Turkish government and its official and unofficial agents and supporters".

Perhaps the most notorious figure to reference the Armenian genocide was Adolf Hitler.

Speaking to commanders of the Wehrmacht on 22 August 1939, Hitler detailed his plans for invading Poland and wiping out the Polish people.

"I have issued the command – and I'll have anybody who utters but one word of criticism executed by a firing squad – that our war aim does not consist in reaching certain lines, but in the physical destruction of the enemy.

"Accordingly, I have placed my death-head formation in readiness – for the present only in the East – with orders to them to send to death mercilessly and without compassion, men, women, and children of Polish derivation and language," he said.

"Only thus shall we gain the living space which we need. Who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians?"

The genocide today

Global recognition of the genocide varies widely.

The majority of European countries - with the notable exceptions of the UK and Ukraine - now recognise the killings as a genocide, as do a number of Middle Eastern countries including Lebanon, Syria and Libya.

Many others have refrained from labelling it as such even if they don't explicitly deny it took place.

Only Turkey and Azerbaijan officially deny the killings constitute a genocide.

The issue is a very sensitive one in Turkey. While the official position of the government and the majority of Turks is that the killings were not a genocide, numerous left-wing, Armenian and Kurdish groups have called for the genocide to be recognised.

One of the most high-profile controversies came in 2005 when a criminal case was opened against best-selling Turkish author Orhan Pahmuk for acknowledging the killing of more than a million Armenians in 1915.

Though charges were initially dropped, the case was later re-opened and he was forced to pay a fine. Ultra-nationalists burned his books at rallies, while the nationalist Hurriyet newspaper denounced him as an "abject creature".

The murder of Hrant Dink, an outspoken advocate for the rights of Turkey's now small Armenian minority, further alerted the country to the problem of the legacy of the genocide.

Dink was shot dead in Istanbul in broad daylight in January 2007. At the time of his murder he had been facing trial on charges of "denigrating Turkishness". Though the responsibility for his killing has been shrouded in controversy, it is generally accepted there was an ultra-nationalist motive.

His death sparked a major outcry across the country. Tens of thousands of people, mostly ethnic Turks and Kurds, marched at his funeral with protesters carrying signs reading "We are all Hrant Dink" and "We are all Armenian."

Akcam has long argued that recognition by Turkey of the genocide would help heal the country's psyche, as well as providing comfort to Armenians.

“The road to peace and democracy in the Middle East passes through the recognition of the Armenian genocide," he said during an interview in 2012.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.