Battle for Idlib: Syrian government assault leaves Turkey facing tough choices

For Muhammad al-Sayyid al-Daghaim, the nearby presence of Turkish forces was once reason to believe that Jarjnaz would be spared the devastation wrought by pro-government forces on other towns and cities in opposition-held areas of Syria.

Jarjnaz, in southern Idlib, had long been known for its anti-government songs and its support for the revolution against Bashar al-Assad, but Daghaim reasoned that his hometown was far from the frontlines and did not host any rebel bases.

The deployment of Turkish troops to an observation post in the adjacent village of Sarman as part of the 2017 de-escalation process agreed between Turkey and Damascus-allies Russia and Iran in Astana, Kazakhstan, gave Jarjnaz residents hope that they could live out the war in relative safety.

But Daghaim told Middle East Eye that Jarjnaz is now in ruins. Its residents have fled, its buildings have been shattered by air strikes and artillery bombardment, and its streets are patrolled by government forces.

“A plane launched attacks and my house was flattened, just as hundreds of houses in Jarjnaz have been destroyed,” said Daghaim, an activist since 2011.

The once-quiet town has been the scene of months of fierce clashes as opposition fighters have sought to halt the advance by pro-government forces into a 15-kilometre-wide de-militarised zone around Iblib’s borders that was agreed in a further round of talks between Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Russian President Vladimir Putin in Sochi in October.

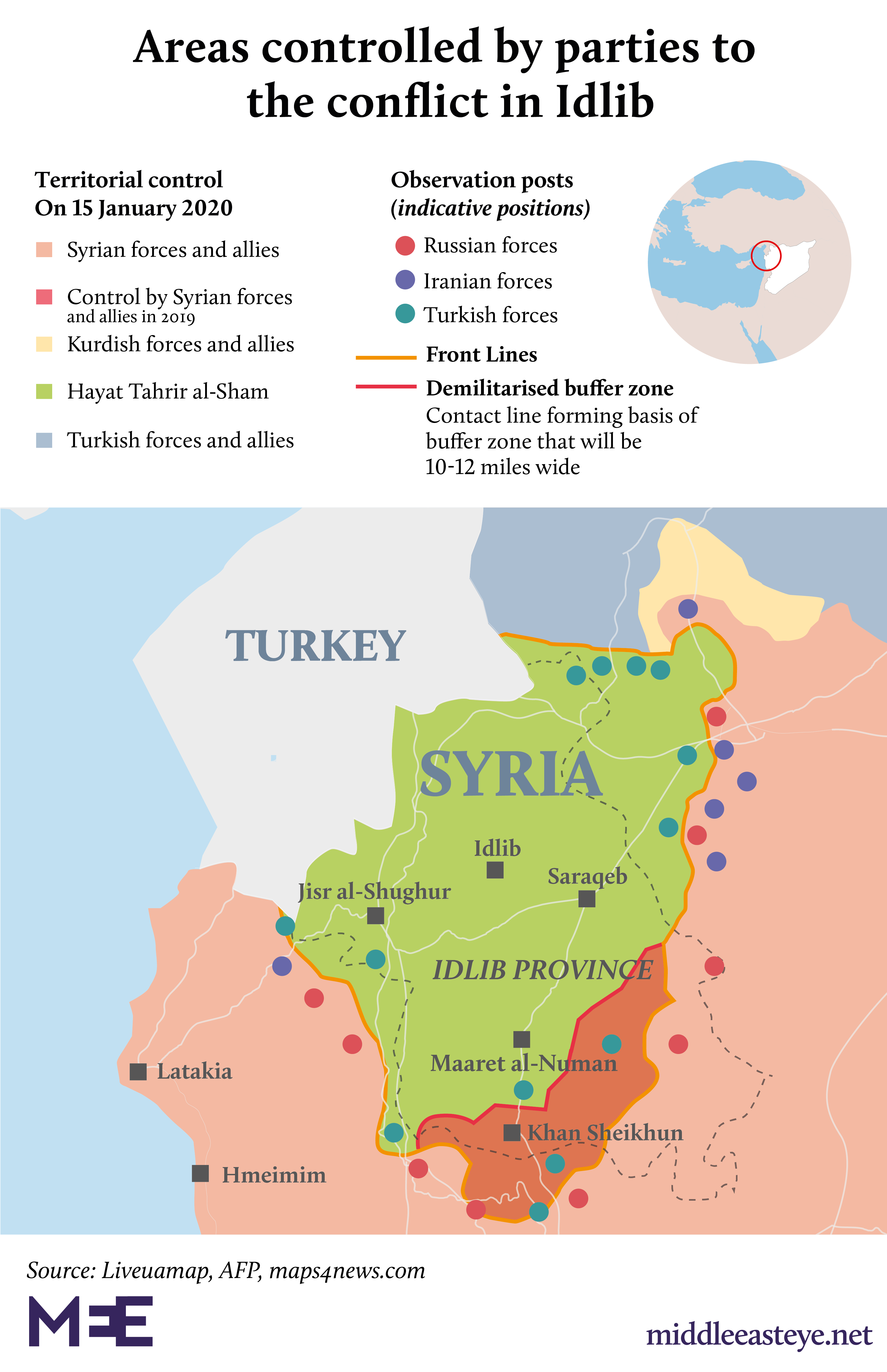

The advance means that two of the 13 Turkish observation posts established in that buffer zone are now encircled by Syrian government forces, including the one in Sarman since August.

Advancing pro-government forces on Monday also surrounded the city of Maaret al-Numan and captured a stretch of the M5 highway, cutting off the main supply route to a third observation post near the village of Maar Hattat in the south of the province.

Agreement violated

Turkey, which backs Syrian National Army rebel fighters who control territory in northern Idlib and northern Aleppo provinces, says that the advance violates its existing agreements with Russia.

Moscow and its allies meanwhile accuse Ankara of breaching the terms of the Astana agreement by allowing Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), a militant alliance containing elements formerly allied to al-Qaeda, to remain in control of the rest of the province.

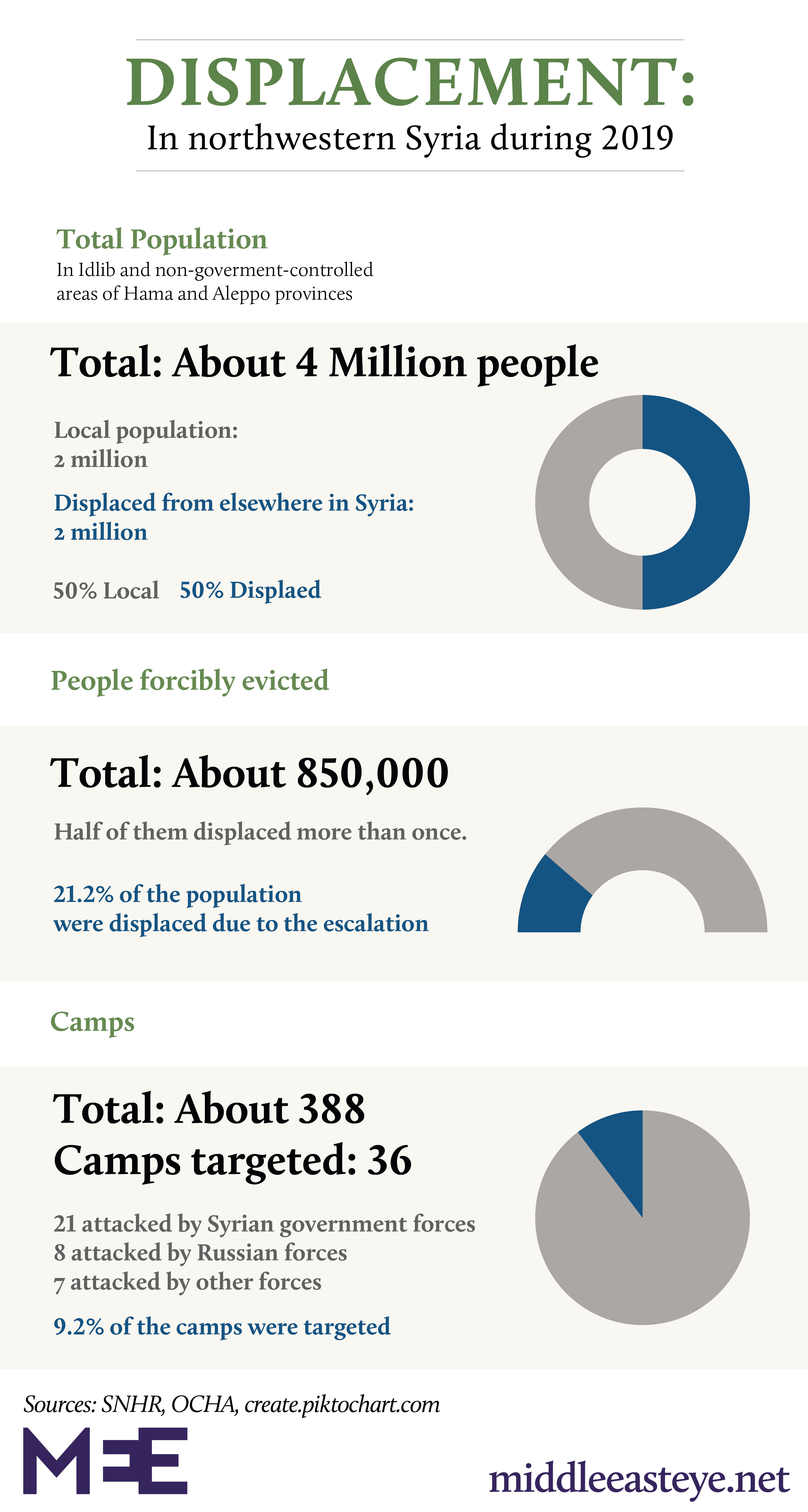

On the ground in Idlib, the main consequence of the latest wave of fighting has been a massive movement of people in a region already hosting about two million from other parts of Syria, including many who have now been displaced multiple times.

Fadel Abdul Ghany, chairman and founder of the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), a London-based human rights monitor, told MEE that at least 850,000 people were displaced within Idlib in 2019.

Abdul Ghany said that at least 72 people had also been killed in Idlib since the most recent ceasefire deal agreed by Russia and Turkey was supposed to come into effect on 12 January. They included at least 21 people killed in an air strike targeting a popular market in Idlib City.

He suggested that Turkey could have withdrawn from the de-escalation agreement in protest at attacks by pro-government forces targeting civilian targets.

“The Turkish Foreign Ministry should have been clearer with the Syrians regarding its role in the agreements with Russia,” he said.

“There are repeated brutal massacres due to the attacks of the Damascus forces and its allies Tehran and Moscow. Ankara could have withdrawn from the agreements because of repeated violations such as the deliberate bombing of hospitals and schools.”

Moscow meeting

Yet Turkish officials have continued to deal with their Russian and Syrian counterparts.

On 13 January, the Syrian state news agency SANA reported that Ali Mamlouk, the head of Syria’s National Security Bureau, had met Hakan Fidan, the head of Turkey’s MIT intelligence agency, in Moscow and called on him to implement the terms of the Sochi deal, including opening the M4 and M5 motorways, the main routes between Aleppo and Latakia and Aleppo and Hama.

Abdul Ghany said the meeting appeared to have been focused specifically on security issues.

The meeting came a day after pro-government forces fired an anti-tank rocket at a Turkish observation post near Andan north of Aleppo and Damascus deployed reinforcements near another observation post south of Aleppo.

“I believe that the meeting does not exceed the security level yet, there is no indication of political coordination between Damascus and Ankara,” said Abdul Ghany.

Some interaction has also been necessary between security forces on the ground. Turkish convoys delivering supplies and soldiers to the two surrounded observation posts at Sarman and Morek, near the town of Khan Sheikhun, have generally been allowed to pass unhindered through government-held territory.

Supplies and reinforcements to another observation post were delayed for several days when a Turkish convoy was attacked by Syrian aircraft in August, but such incidents have been rare.

Turkish officials spoken to by MEE on condition of anonymity insist that Ankara continues to support the Syrian opposition and civilians trapped in the warzone as much as possible.

But they say that the determination of Damascus and Moscow to re-take opposition-held territory and Russia’s control of the skies makes enforcing any kind of safe zone virtually impossible, especially without wider international involvement.

Ankara will not further risk the lives of Turkish soldiers to dislodge Islamist militants from Idlib or to confront Syrian government forces, they say.

'In the event that a political solution is reached in Syria that requires a rapprochement with Damascus, I do not think Ankara will hesitate'

- Muin Naim, political researcher

However analysts told MEE that the future of Turkey’s military presence in Syria and its future relationship with Damascus would likely be influenced by calculations surrounding its broader alliances with Russia and Iran and achieving its own strategic goals.

“In politics, there is no absolute hostility or absolute friendship. Turkey is primarily concerned with protecting its interests and then influencing the future of Syria,” Muin Naim, an Istanbul-based political researcher specialising in Turkish affairs, told MEE.

“In the event that a political solution is reached in Syria that requires a rapprochement with Damascus, I do not think Ankara will hesitate.”

Since 2016, Turkey has launched three military operations in northern Syria, all targeting areas controlled by Kurdish forces: Euphrates Shield in 2016-2017 and Olive Branch in 2018 in northern Aleppo province, and Spring Peace in eastern Syria late last year.

Ankara says these operations are necessary to protect its borders from Kurdish fighters linked to the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), which is considered a terrorist group by Turkey.

Turkey’s security interest in northern Syria predates the country’s conflict, with the 1998 Adana Agreement by which Syria agreed to expel the PKK from its territory also granting Turkey the right to pursue suspected PKK fighters into Syrian territory.

Rules of engagement

Samir Nashar, a senior figure within the Syrian opposition in Turkey, told MEE that Ankara’s interest in attacking Kurdish-held Syrian territory had often converged with Damascus’s interests as it also enabled Syrian government forces to re-enter areas where opposition control had been weakened.

“Turkish military operations inside Syria were in the interest of Damascus,” said Nashar, who speculated that the Syrian government offensive to recapture rebel-held areas of eastern Aleppo in late 2016 had been conducted with tacit Turkish consent in return for Damascus allowing Turkey's Euphrates Shield incursion to go unchallenged on the ground.

“In exchange for Euphrates Shield, Damascus forces took control of Aleppo in late 2016, which caused an imbalance between government forces and opposition forces.

“Damascus forces, in cooperation with Russian mercenaries, were unable to cross the Euphrates, but after the Turkish intervention in eastern Syria, they easily entered the area.

“Despite the presence of the Syrian National Army supported by Turkey in the north of Aleppo, there was no battle between this army and Damascus forces."

Ankara even handed over 18 pro-Assad fighters to Syrian authorities, under the supervision of the Russian military police, who were captured during a rare clash between Moscow-backed forces and Turkish-backed rebels north of Aleppo.

“The Aleppo-Euphrates Shield deal set the rules of engagement, and this was done between Russia and Turkey, and the opposition forces and the government were obliged to adhere to them,” said Nashar.

Naim and Nashar agreed that Turkish forces would likely remain in Syria for as long as Ankara considers Kurdish forces operating from within Syrian territory to be a threat to its national security.

"I think the Turkish forces will remain in Syria until there is a change in the nature of the Kurdish military presence on the Syrian-Turkish border," said Naim.

Nashar said that such a scenario would likely involved a political solution in which all areas of Syria are ultimately brought back under Syrian government control.

“The Turkish position focuses on ensuring the security of its borders, and ending the presence of the Kurdish forces associated with the PKK,” he said.

De-escalation deals

Analysts suggest that past de-escalation deals in eastern Ghouta, Daraa and areas of northern Homs, which were endorsed by Ankara, Tehran and Moscow, could be a template for a resolution in Idlib, even with the consequence of effectively handing formerly opposition controlled territory over to the government.

Nashar said that international approval for such deals had left opposition fighters dependent on foreign support with no one to turn to. Many subsequently surrendered in return for safe passage to Idlib as part of the de-escalation deals.

“The rebels did not take into account the possibility of deals, and they were not ready to fight without relying on the countries [supporting them], especially those neighbouring Syria, so they surrendered as soon as the countries abandoned them,” he said.

Many fighters found themselves faced with the option of reconciling with Syrian government forces or being displaced to northern Syria, where most of them joined the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army.

In Idlib, hardline Islamist fighting groups have mostly rejected all agreements between Russia and Turkey, describing them as tantamount to surrender, although HTS does not have an official position.

As well as seeking to uphold the security of its southern border, Naim said Turkey was also seeking an eventual peace settlement on the best terms for it to benefit economically from reconstruction projects and trade.

“Syria is Turkey's economic gateway to the Arab world, especially the Gulf, in addition to the trade exchange between the two countries,” he said.

'Any political solution will not take place without Turkey, which is seeking to improve its relations with the future Syria'

- Muin Naim, political researcher

“Any political solution will not take place without Turkey, which is seeking to improve its relations with the future Syria.”

Turkish officials say that behind-the-scenes contact with Syrian officials is nothing new, but they insist that Erdogan will never re-establish formal ties with Assad.

Still, they acknowledge that an arrangement that serves both sides in the medium term, possibly involving the creation of an enclave along the border for civilians, is a plausible scenario.

For now, however, Daghaim told MEE that civilians were paying the price as Ankara, Damascus and Moscow continued to barter over their lives and security.

“Civilians were the biggest losers from Ankara’s agreements in Sochi and Astana, while Damascus and Moscow have made significant gains,” he said.

Daghaim said that he had already fled to Turkey, following millions of other refugees across the border. The latest fighting has stretched Idlib’s already overcrowded and under-resourced camps for the displaced to breaking point.

“There is no safe area left in Syria,” he added.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.