Boris Johnson's ancestral village pledges to sacrifice sheep in his honour

KALFAT, Turkey – In the small village of Kalfat in the heart of Anatolia, residents say they would be more than happy to welcome the British Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson by sacrificing sheep in his honour, repainting the buildings in the village, and giving him the full red carpet treatment.

Kalfat in Cankiri province is the ancestral homeland of Johnson’s paternal great-grandfather, Ali Kemal, and residents of the village take immense pride in the political achievements of someone they consider one of their own.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

They are mostly happy to forgive him his anti-foreigner and specifically anti-Turkish stance since he became a campaigner for "Brexit".

Prior to June's referendum on whether the UK should remain in the European Union, leave campaigners had repeatedly argued that remaining in the EU would allow millions of Turks to move to Britain.

Johnson, who also gained headlines in May regarding a rude poem he wrote about Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, arrived in Turkey on Monday for his first visit to the country in a diplomatic capacity, including a meeting with Erdogan.

Yet despite those controversies, the affection he enjoys in Kalfat is such that he is not referred to as Mr Johnson or even Boris Johnson by many, but simply as “our Boris".

“We will sacrifice many sheep in Boris’ honour. We will repave our roads, repaint our buildings. We will give him the complete red carpet treatment if he visits his ancestral village,” Adem Karaagac, the village headman, told Middle East Eye.

Karaagac says many of the village residents share the same genetic traits as Boris and that there are quite a few people in the village with blonde hair and pale skin.

“But what I have noticed on television is that his mannerisms and body movements also strongly resemble those of the people in our village,” said Karaagac.

“It’s a small village and many of the people are distantly related. Even my wife is somehow related to Boris. I am not sure of the exact connection though.”

According to Karaagac, the initial disappointment they felt when Boris didn’t directly succeed David Cameron, the prime minister who was forced to quit as a result of the leave campaign's victory in the referendum, was replaced by a feeling that it might actually be for the better.

“Our Boris was ready to be prime minister. But now he can gain more experience as foreign minister before becoming prime minister. That will be better for him as well.”

The village is not a stranger to visits by the Johnson family. Boris’ father Stanley, a former MEP, visited in 2008.

“My predecessor sacrificed a sheep in his honour when he visited. I believe he spent a really nice day in our village,” said Karaagac.

Stanley Johnson’s visit was to trace his family’s roots, and at the time he told media that he was interested in tracing the lineage of all sides of his family, which included Turkish, Swiss and English roots.

Turkish roots

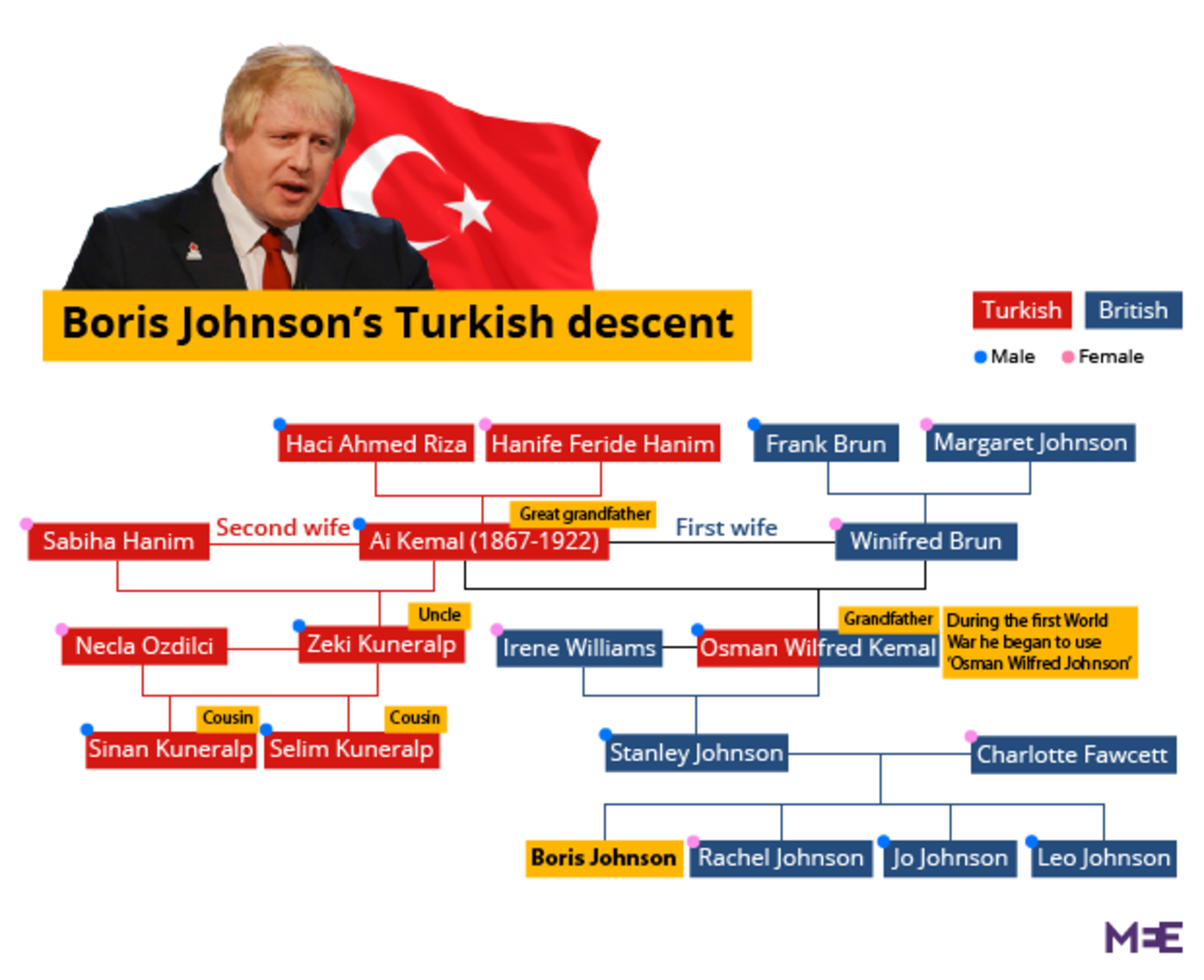

The Turkish side of his story started in Kalfat, some 350 kilometres east of Istanbul. Ali Kemal’s father was a wax merchant from Kalfat who traded in the then imperial capital Istanbul. Ali Kemal, born in Istanbul, went on to become a journalist and diplomat.

He married twice. Once to an Anglo-Swiss woman called Winifred Brun and the other to a Turkish girl called Sabiha.

The Turkish side of the family also took up a career in diplomacy. Sabiha’s son Zeki Kuneralp served in the Turkish foreign service and his son Selim, Boris’ cousin, was a Turkish ambassador until his retirement last year. However, unlike the others in their ancestral village, Kuneralp has spoken out against his cousin and his views, slamming his “little Englander” stance and saying that under Johnson’s policies “his own grandfather wouldn’t have been able to come to the UK”.

Kemal fled to exile in the UK in 1909 following a press crackdown but returned before the outbreak of the World War One. In 1919, he openly advocated for a British protectorate status in Turkey, something which caused him to be seen as a traitor by Turkish nationalists led by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk who went on to found the modern Turkish republic, and led to Kemal being lynched by an angry mob in 1922. Kemal’s son Zeki only returned to Turkey from exile in Switzerland after Ataturk’s death in 1938.

In 2015, Johnson also won himself the description of traitor in Turkey after he said that his sympathies lay with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), an entity listed as a terrorist organisation by Turkey, the UK and the US. Turkey has been involved in an armed conflict with the PKK since 1984.

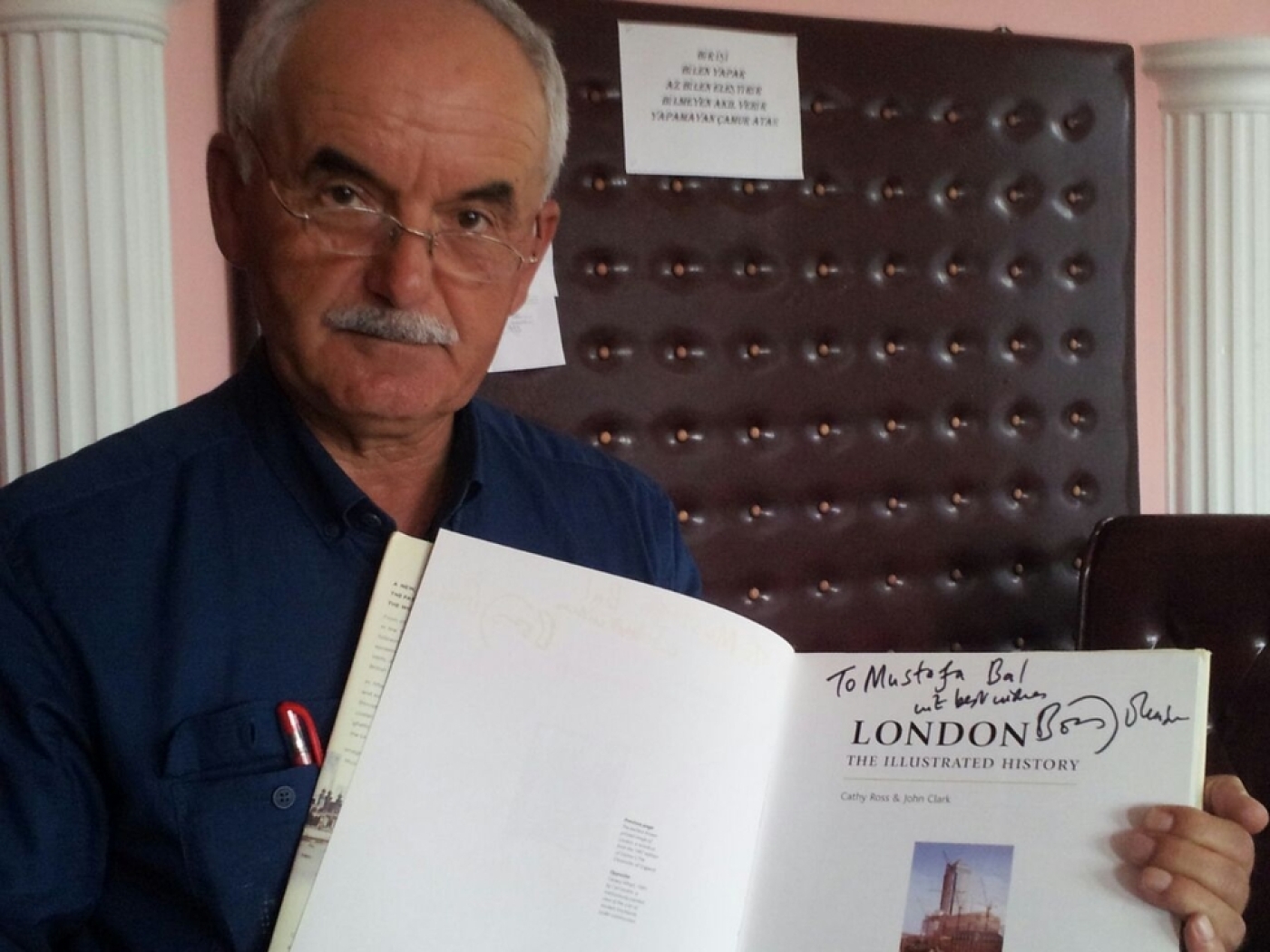

Stanley Johnson’s visit in 2008 was not his first to Kalfat village and one man who was there during the first visit is 69-year-old Recep Akdogan.

“It was 1961 or 1962 when Zeki Kuneralp and Boris’ father visited our village. I was in primary school then and didn’t understand what the fuss was about. I hadn’t yet read about Ali Kemal and all that,” Akdogan told MEE.

Akdogan is one of the few residents of Kalfat who says Boris is not welcome unless he retracts his support for terrorists.

“Boris Johnson better not think of visiting here after those things he said about supporting the PKK and posing with their members with a rifle in his hand. The people in our village are patriots and we don’t want him here,” he said.

Yusuf Islam Sekerci, a 19-year-old university student in Kayseri who returns home to Kalfat during the summers, is quick to interject and show that Akdogan is in the minority when it comes to Boris.

“Of course Boris is welcome here even if he said those unfortunate things. This is his village. We will display the legendary Turkish hospitality to him if he chooses to visit,” Sekerci told MEE.

Karaagac, the village headman, is more diplomatic about Boris’s PKK remarks and says it was just a political gimmick.

“He was made to speak such things. It was all part of a political game. The English are good at those kinds of political games,” he said.

“I don’t think Boris is a PKK sympathiser if has even one drop of Turkish blood, which he has plenty of as we know.”

While many in Kalfat were aware of Boris’ remarks concerning the PKK, few knew or appeared to care about the offensive poem he penned about the Turkish president in The Spectator magazine in May.

Bunyamin Mermerkaya, 35, told MEE that the village would gladly host Boris regardless of what he has done or said, and that the village would celebrate his achievement of becoming foreign secretary.

“We will welcome him. We will sacrifice a sheep in his honour. He is from here and he has made our village proud, first by becoming mayor of London and now foreign minister of England.”

On whether village residents would like Boris’ first visit to his ancestral village of Kalfat to be as foreign minister or prime minister, most seem to agree with Karaagac’s view.

“I don’t care if Boris comes here as foreign minister or prime minister. I want him to come here as a son of Kalfat, as a son of these lands. We will greet him dressed in our finest.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.