The choices Iran now has to make

No Iranian president has failed to be re-elected at the ballot box during the history of the Islamic Republic.

Will current office-holder Hassan Rouhani become the first, when Iranians vote on Friday, 19 May?

It’s unlikely. Rouhani needs 50 percent of the vote to avoid a run-off on 26 May. The architect of the 2015 nuclear deal and a member of the centre-right Moderation and Development party, he is the default candidate for most of the Iranian elites, as well as many reformist voters.

Even though he is not a reformist himself, Rouhani has secured the backing of Mohmmad Khatami, president from 1997 until 2005 and the original leader of the reform movement.

Foreign policy did not feature prominently in the three debates. Even the 2015 nuclear deal, was only discussed in relation to sanctions relief

The international community, especially Western governments, also support Rouhani, partly because he secured that nuclear deal, partly because of his perceived pro-Western tilt and desire to open up the economy to foreign investment.

The stakes are high as the incumbent faces a highly visible challenge from leading conservative Ebrahim Raissi, a senior member of the Combatant Clergy Association.

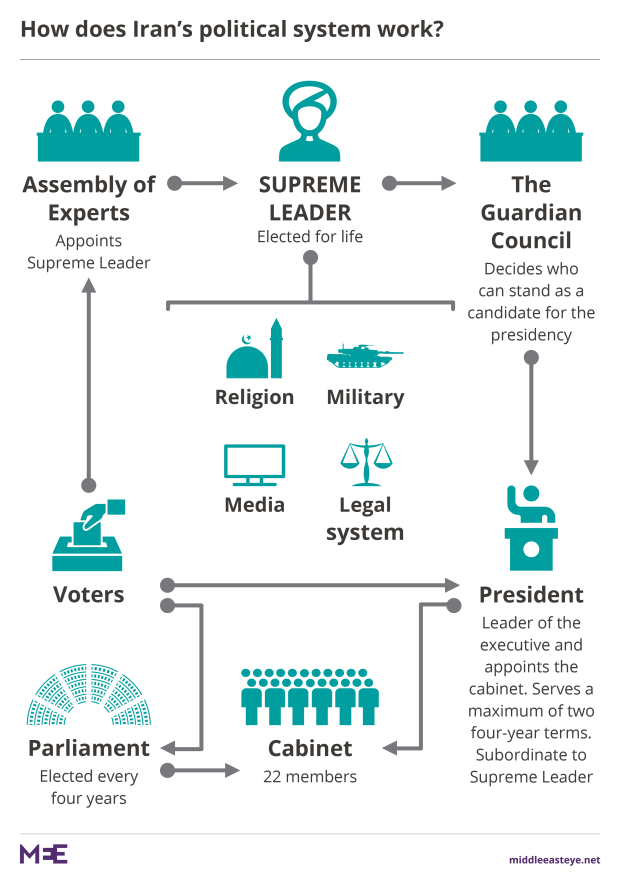

None of the candidates – who were approved by the Guardian Council from a list of 1,600 - have strong party machines behind them, instead relying on interviews with the state broadcaster and other media outlets.

The three live televised debates, the last of which was on Friday, are their most effective means of reaching out to the electorate directly.Foreign policy did not feature prominently in the three debates. Even the 2015 nuclear deal, officially known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA, or “Barjam” in Persian), was only discussed in relation to sanctions relief.

All the candidates support it: none has talked about reneging on it. Other foreign policy issues, such as Iran’s role in Syria and tensions with Saudi Arabia, were barely mentioned.

Historically, Iranian voters tend to be influenced more by bread and butter economic issues as opposed to foreign policy. Although inflation stabilised after the nuclear deal there are wider acute economic concerns related to unemployment, unfair distribution of resources and corruption.

Debates and departures

Can Rouhani be beaten? Only if his opponents throw their weight behind one strong candidate.

By the end of the third debate, the vote of the traditional conservatives and the more conservative principlists was split three ways between Ebrahim Raissi, Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf and Mostafa Mirsalim.

Ghalibaf performed much more strongly in the debates than Raissi, only to drop out of the race on Monday. He has now endorsed Raissi, whose prospects have improved and who now has the backing of the “Popular Front of Islamic Revolution Forces” (JAMNA), a makeshift conservative umbrella coalition formed late last year.

Iran’s next president faces two critical foreign policy issues: effectively containing the threat from an increasingly belligerent United States; and the escalating tension with Saudi Arabia

Whoever wins, Iran’s next president faces an uphill task in stabilising the post-sanctions economy as well as dealing with two critical foreign policy issues which are likely to come to a head during the next four years.

The first is how to effectively contain the threat from an increasingly belligerent United States, led by the mercurial Donald Trump, who has said that Iran “is playing with fire” with its regional policy.

The second is the escalating tension with Saudi Arabia that has played out in the context of regional proxy wars, most notably in Syria and Yemen. Saudi Arabia’s deputy crown prince, Mohammad bin Salman, has ruled out dialogue with Iran and in a potentially dangerous escalation has threatened to take the struggle for regional influence “inside” Iranian borders.

Here’s how the candidates line up in what is likely now to be a straight race between Rouhani and Raissi…

Hassan Rouhani

Current position: President

Previously: Secretary of the Supreme National Security Council (SNSC), deputy speaker of parliament.

Why he matters: Rouhani has been at the heart of the Iranian defence and security establishment for nearly 40 years. He was pivotal to the management of the nuclear crisis, first as secretary of the SNSC, when he negotiated a deal with three major European states in late 2003, then as president from 2013 onwards, when he negotiated the landmark nuclear deal.

Despite his background, Rouhani has welded a very broad coalition comprised of reformists, centrists and technocrats, which performed better than expected at last year’s parliamentary elections when it eliminated the conservatives’ majority.

Rouhani won the 2013 presidential election primarily because he was supported by two former presidents: Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani (who died in January) and Khatami.

Rafsanjani had a narrow but hugely influential following from the kargozaran (technocrats), a bureaucratic and financial elite dedicated to rationalising the Iranian economy through privatisation and integration with the global economy. Khatami is regarded as the spiritual leader of the Iranian reform movement and boasts a huge following across the country.

This tactical alliance gives Rouhani a considerable, and possibly unassailable, advantage over his rivals. Moreover, his national security background means he is trusted by the powerful security establishment.

In terms of the Iranian political landscape Rouhani is seen as a centrist candidate who embraces notions of economic rationality, policy consistency and bureaucratic supremacy.

A Rouhani victory would keep Iran’s embattled reform movement afloat, giving it the chance to make a serious comeback when the opportunity arises.

What he said in the debates: Rouhani’s performance during the debates was generally regarded as poor, relying on his running mate Eshaq Jahangiri (see below) to back him up with facts and figures. The president spent much of the time defending his four-year record and promising consistency and greater effort at improving the economy if he is elected for a second term.

He also attacked his main rivals’ backgrounds, accusing them of being involved in “detentions and executions” for decades. It was widely regarded as hypocritical, given Rouhani’s own supression of dissent and protests in the past.

Ebrahim Raissi

Current postion: Custodian of Astan Quds Razavi

Previous postion: Attorney general, deputy chief justice, member of Assembly of Experts

Why he matters: Raissi is a close ally of Ayatollah Seyed Ali Khamenei, Iran’s leader and as such is the establishment candidate.

As the custodian of the Imam Reza shrine in Mashhad, he presides over a vast commercial and charitable empire which employs tens of thousands and boasts revenues in the region of an estimated $15 billion.

With a solid judicial background going back to the 1980s, Raissi is widely viewed as an unflinching and ruthless guardian of the clerical establishment. He has been implicated in the mass execution of militants and political prisoners during the summer and autumn of 1988 after the end of the Iran-Iraq War.

As the official candidate of JAMNA, Raissi is hoping to become the country’s first conservative president since Khamenei served from 1981 to 1989. Ghalibaf’s departure, and subsequent endorsement, of Raissi make his task much easier – but the 57 year-old cleric still faces an uphill task in trying to unseat Rouhani.

For a start, Raissi does not have a political background and, until the beginning of this year’s campaign, was largely unknown to the public.

Furthermore, his mild and unassuming manner, coupled with a distinct lack of charisma, means he will struggle to influence non-conservative voters.

What he said in the debates: Raissi scored points by exercising self-control and avoiding tit-for-tat exchanges with Rouhani and Jahangiri. He also produced a coherent narrative centred on social justice and the fight against corruption. But Raissi was ridiculed for calling for a crackdown on tax avoidance and evasion when the Astan Quds Razavi he controls enjoys tax-exempt status.

Mostafa Mirsalim

Current position: Expediency Discernment Council

Previous positions: Minister of culture and Islamic guidance, police chief

Why he matters: As a leading member of the Islamic Coalition Party (Hezbeh Motalefeh Eslami), Mirsalim is an old school capitalist and right-winger. With his designer beard, tuxedos and propensity to show off his command of French, Miraslim cuts an eccentric figure. Widely viewed as a minor candidate, Mirsalim is not expected to perform strongly on election day.

What he said in the debates: Mirsalim provided a sweeping and uncharismatic critique of Rouhani’s record and lamented the state of national affairs generally. He shocked many with his insufficient grasp of vital national statistics, even though he sits on the Expediency Discernment Council, which mediates on disputes between the three branches of government.

Mostafa Hashemitaba

Current position: Head of national Olympic committee

Current position: Head of national Olympic committee

Previous positions: Minister of industry

Why he matters: Hashemitaba could be described as the only genuine reformist candidate in the race, albeit a tentative one. In essence he is a technocrat who was close to Rafsanjani, while also close to leading reformists such as Khatami, adopting some of their rhetoric, if not their principles.

A close ally of Rafsanjani, in 1996 Hashemitaba co-founded a technocratic political party by the grandiose name of “Executives of Construction” (Kargozaraneh Sazandegi). This party – like most in Iran – is a platform for elites and has little or no grassroots base.

What he said in the debates: Even taking into account his minor role in the campaign, Hashemitaba performed exceptionally poorly. Broadly supportive of Rouhani, he failed to present any new ideas, let alone set out a cohesive policy platform.

Withdrawn

Eshaq Jahangiri

Current position: Vice president

Previous postions: Minister of industries and mines, provincial governor

Why he matters: Jahangiri pulled out of the race on Tuesday as many observers had expected. He is part of the president's inner circle and was universally regarded as a “support” candidate for Rouhani.

But his candidacy was important for two reasons, aside from his backing of Rouhani. First, Jahanigir is a protégé of former president Hashemi Rafsanjani and a leading light of the kargozaran (technocratic) trend, making him an important link between the technocrats and the centrists allied to Rouhani.

Second, Jahangiri's strong performance during the campaign, and especially in the televised debates, had many speculating that he may contest the presidency for real at the next election in 2021.

What he said in the debates: Jahangiri’s main role was to support Rouhani, by providing facts and figures, and coordinating attacks on his main opponents.

In the first debate, he went on the attack while Rouhani played defence. They then reversed roles during the second debate. For the third debate, both candidates went on the offensive against Ghalibaf and Raissi.

Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf

Current position: Mayor of Tehran

Previous positions: Chief of police, Islamic Revolutionary Guards (IRGC) commander

Why he matters: A conservative with appeal among younger voters, Ghalibaf fought a hard campaign and disappointed many by declaring his withdrawal from the race on Monday 15 May. Widely seen as the candidate of the “deep state”, Ghalibaf has a long military and security record, including a stint as commander of the IRGC air force during the late 1990s.

Derided by his opponents for his reportedly tough and militaristic approach to dissent management, Ghalibaf nevertheless showed decorum, patience and self-restraint during the debates.

Unlike Raissi, the colourful and flamboyant Ghalibaf was well-placed to reach out to reformist voters by appealing to nationalism, law and order and social justice.

His departure does not necessarily spell the end of his political ambitions: Ghalibaf could contest the next presidential election in May 2021.

What he said in the debates: Ghalibaf was Rouhani’s and Jahangiri’s most credible opponent. He continually took the fight to Rouhani by exposing the incumbent’s insufficient grasp of facts and figures as well showcasing his empty promises.

Ghalibaf accused Rouhani and Jahangiri of being the candidates of the “4 percent”, whilst the remaining “96 percent” have to contend with harsh economic conditions.

By associating Rouhani and Jahangiri with the country’s secretive financial elites, Ghalibaf made a convincing case of their inability – indeed, their unwillingness - to fight corruption.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.