Cholera in Yemen: Fighting deadly disease in face of war and siege

AL MUKALA, Yemen – Abdul Salam, a middle-aged Arabic teacher living in the remote tribal village of al-Mansouri in Yemen's Bayda province, suddenly suffered severe diarrhoea and vomiting late last year. His relatives suspected he had fallen victim of a cholera outbreak that had killed four villagers a few days before, but there were no healthcare facilities or doctors in the area to treat his symptoms.

The war-torn country has been battling a significant cholera outbreak since mid-October 2016. The death toll of the outbreak reached 11, out of 180 confirmed cases, while suspected cases reached 15,658 as of 11 January, according to a joint report by a health ministry task force and several UN bodies.

When they finally reached the hospital, I was incapacitated

- Abdul Salam, cholera patient

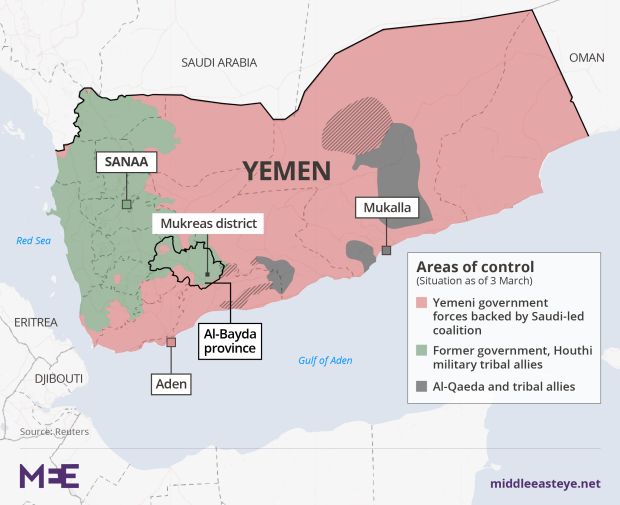

Bayda is largely controlled by Shia Houthi rebels and their allies, who have been fighting against the internationally recognised government of Abd Rabbuh Mansour Hadi. Hadi has been supported since March 2015 by a Saudi-led coalition.

To reach the nearest public health clinic in Mukaeras town, Abdul Salam's family had to cross into Houthi-controlled territories where the militia imposes a night-time curfew to curb al-Qaeda attacks. Previously an al-Qaeda hotbed, the militant group now controls the province's remote and peripheral areas.

"When they finally reached the hospital, I was incapacitated," he told MEE.

"My body had been drained from top to bottom," he said while explaining that his vomiting and diarrhoea spells left his body increasingly dehydrated.

His relatives had driven for one hour on a rugged and dangerous road to reach Mukaeras's only healthcare facility.

Lack of resources

"When I arrived [at the clinic], there were no doctors on duty," he said. "Nurses gave me some injections but that didn't work."

More than 14 million people in Yemen have no access to health services, the United Nations health agency said in March, warning that transportation of medical personnel and treatment for the injured had become increasingly difficult.

Doctors were already scarce in Yemen's rural areas. Since the war started, many have deserted their jobs due to months of unpaid salaries.

Days later, and as his health continued to deteriorate, Abdul Salam was taken to a more advanced private hospital in Bayda city.

Although his family was relieved Abdul Salam was finally being treated, they could only afford to keep him hospital for a few days.

"I stayed there [hospital] for several days, then decided to go back home. The medical bill was just too high,” said Abdul Salam, explaining that it had cost his family almost $110 a day to keep him in hospital.

After leaving the facility, Abdul Salam moved to Aden in order to be close to a dialysis centre, a facility that does not exist in his village.

Abdul Salam now has only two wishes.

“I want this war to come to an end and I want to start teaching again here in Aden, next to my dialysis centre.”

Government response

Following a number of reported deaths as a result of the cholera outbreak among villagers in Bayda last year, the ministry of health’s provincial office in Baydha sent a team of medics to assess the situation in the area.

The team included doctors, nurses and medical technicians. Jalal Sanah, the doctor leading the team, said they were appalled by the dire health conditions in al-Mansouri village and other neighbouring areas.

By early this year, nearly 1,145 people in the [Mukeras] district were suffering from acute watery diarrhoea

- Jalal Sannah, doctor in Bayda province

"When we arrived, the cholera had already killed several people and dozens of others had contracted the disease and were suffering severe diarrhoea and vomiting," Sanah told MEE.

More than a fifth of Moukeras' population of about 5,000 people were suffering symptoms associated with the disease, Sanah told MEE.

"By early this year, nearly 1,145 people in the district were suffering from acute watery diarrhoea [AWD- a symptom associated with cholera]," Sanah said.

For several weeks, the team crisscrossed villages treating suspected cholera cases and sending critical ones to better health facilities in Bayda city. Meanwhile they helped raise health and hygiene awareness among the villagers to limit the spread of the disease.

The team's treatment plan and awareness activities resulted in tangible improvements.

According to Sannah, the number of suspected cholera cases in Moukeras dropped from 56 per day to 18, while the number of deaths had dropped to zero by the time the team left the area.

Wider challenges

Despite reaching dozens of people, Sanah said his team only scratched the surface of the problem. He says more efforts are needed to remove the breeding grounds of the disease.

'You cannot ask people to build a toilet if they cannot afford to buy food for their children'

- Jalal Sannah, doctor in Bayda province

"The main causes of cholera outbreak still exist," said Sanah. "There is no sewage system or clean drinking water and reservoirs are left unprotected.

"There are no toilets and people relieve themselves in the open. But you cannot ask people to build a toilet if they cannot afford to buy food for their children," he added.

Sanah explained that without addressing these structural issues, the disease would continue to spread throughout the country.

Thousands of Yemenis suffered from cholera early this year as healthcare has deteriorated as a result of the war. According to the UN World Health Organisation (WHO), only 45 percent of the country's health facilities remain fully functional and accessible and at least 274 have been damaged or destroyed during the conflict.

Foud Edris, a medic and the director of Bayda provincial health office, told MEE that his office had documented 20 deaths and 2,300 suspected cholera cases since late last year, saying that most of the cases had been in Moukeras and al-Shourejah districts.

"We are under a siege because of the war. Vital drugs are not arriving on time and blood samples take lengths of time to reach Sanaa," Edris said, explaining that the Houthi-controlled capital of Sanaa is the only place with specialised laboratories.

Acute shortage of critical medicines, limited fuel for electricity and a limited number of specialised medical staff such as intensive-care doctors and nurses have also exacerbated the healthcare situation in Yemen, according to the WHO.

Baby steps

Despite the many challenges, recent efforts by government bodies and international NGOs have managed to limit the spread of the disease.

Although statistics on the number of recent cholera cases do not exist, sporadic reports from provincial officers point to a dramatic decrease in deaths and suspected cases.

Abdul Nasser al-Wali, the director of ministry of health office in Aden, told MEE that health facilities in the city had not recorded any new cases since February.

"In the early days of cholera outbreak, we were not ready as we had just got out of a war," he told MEE as he explained that prevention and awareness campaigns were later launched to address the issue.

"We now have strengthened partnerships with local and international organisations to fight the spread of this disease."

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.