Closed Al-Aqsa gate reopens old Palestinian wounds in Jerusalem

Tensions have risen once again in the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound, as the status of a long-closed gate to the religious site has sparked renewed fears among Palestinians of Israeli attempts to change the status quo.

Members of the Waqf - the Islamic endowment in charge of the holy site - opened the al-Rahmeh Gate to the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound on 14 February and prayed in the area.

Israeli forces responded on Sunday by sealing the gate with iron chains. Palestinian worshippers and activists reacted by breaking the newly placed chains and organising prayers outside the al-Rahmeh Gate in protest.

In confrontations that have ensued since Monday, Israeli forces assaulted several people at the scene and arrested at least 19 - the majority of whom have been released with bans on returning to Al-Aqsa for at least two months.

Israeli forces removed the chains a day later, but the Gate remains closed. Palestinians have since continued to pray outside al-Rahmeh Gate.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

“Israel seeks to turn al-Rahmeh Gate into an abandoned area with a view to facilitating the annexation process,” Palestinian Authority Minister of Jerusalem Affairs Adnan al-Husseini, a newly minted member of the Waqf, said on Wednesday.

For many Palestinians, particularly Jerusalemites, Israel’s response was yet another provocation in the highly sensitive issue of control over the religious site - amid broader Israeli claims to sovereignty over all of Jerusalem.

Expanded Waqf council

While Israel wrested control of East Jerusalem and the West Bank from Jordan in the 1967 war, the Hashemite kingdom has nonetheless retained control over the Al-Aqsa compound itself through the Islamic Waqf that administers the holy site.

Israel, however, controls all areas outside the compound as part of its annexation of East Jerusalem, where the Old City lies.

On 14 February, the Jordanian government agreed to expand the number of members in the Waqf administrative council from 11 to 18, for reasons that remain unclear.

The newly expanded council headed that same day to the al-Rahmeh Gate, which has been closed off by Israeli forces since 2003.

“We went in to renovate – the hall had been abandoned for ages and there was decay from the rain,” Ekrima Sabri, the head of the Supreme Islamic Committee and new member of the Waqf, told Middle East Eye.

“After that, we decided to pray. The Israeli reaction was that we prayed without their permission, so they placed iron chains,” he added. “We are praying in our mosque. We have every right to pray on every inch of the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound.”

Ziad Ibhais, a researcher on Jerusalem, says that the developments in the last week were about a show of power.

“Israel intended to send the message it is the only legitimate and supreme authority in Jerusalem, even though it is the Waqf that is responsible for the administration of Islamic holy sites in the city, as per international law,” Ibhais told MEE.

Reclaiming a deserted gate

In the saga of Israeli-Palestinian tensions at Al-Aqsa, al-Rahmeh Gate has its own history.

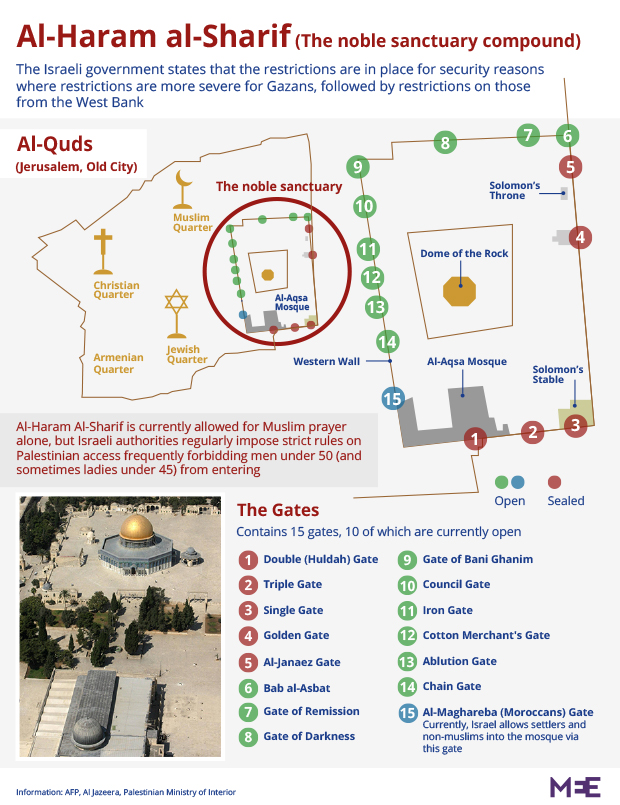

Bab al-Rahmeh, whose name means Gate of Mercy, is a large hall that is part of the bigger Bab al-Dhahabi, or Golden Gate.

Al-Rahmeh once led to the vast courtyards housing the Dome of the Rock and the Al-Aqsa Mosque. It lies on the grounds of the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound and is registered under Waqf lands.

During the Ottoman period, the gate was closed off from the inside and the space was subsequently turned into a hall. A centuries-old Islamic cemetery sits just outside, where the graves of two of the Islamic prophet’s companions lie, making it religiously significant.

For decades, the Islamic Heritage Committee of the Al-Aqsa Mosque used the Gate’s hall as offices and for hosting religious classes as well as activities for the community. But in 2003, Israeli police closed the gate from the outside, claiming the association was linked to the Gaza-based armed resistance group, Hamas.

In subsequent years, the gate was opened only once a year for students of the Al-Aqsa Sharia School for Girls, to sit their high school matriculation exams due to a lack of space.

“What we meant by praying there was that we want to start using this hall as it was used in the past – for teaching, for praying, for religious activities,” Sabri said.

In 2017, the Israeli Magistrate Court in Jerusalem ruled that the hall had to be shuttered indefinitely, in response to a request from the head of police, Roni AlSheikh.

“The Palestinian street in Jerusalem is waiting for an opportunity to bring the issue of Al-Aqsa back into the frame,” Hanadi Qawasmi, a journalist from Jerusalem, told MEE. “Every time there is momentum in the people’s commitment to defend Al-Aqsa, Israel tries to consolidate and intensify its control.

“It’s not about an iron chain that didn’t make any real difference to the situation,” she added. “It’s about the people’s right to use al-Rahmeh Gate.”

Site of tensions

The fear of an Israeli plan to divide the Al-Aqsa Mosque between Muslims and Jews has lingered in the Palestinian subconscious since 1967.

Under international humanitarian law, an occupying power is forbidden from making any changes that would permanently alter the nature of the territory. Israeli control of East Jerusalem, including the Old City, also violates several principles under international law, which outlines that an occupying power does not have sovereignty in the territory it occupies.

However, Israel demolished an entire Palestinian neighbourhood – the Moroccan Quarter in the Old City - immediately after the 1967 war to make room for a large plaza adjacent to the Western Wall at which Jews could pray.

'We have every right to pray on every inch of the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound'

- Ekrima Sabri, former grand mufti of Jerusalem

In the years that followed, Israel began facilitating the entry of non-Muslim visitors to the Al-Aqsa compound, abiding by Jordan’s request to limit the number of groups and to ban certain Jewish fundamentalist groups.

Jewish Israelis believe that the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound stands atop where the Second Temple once stood, and some far-right Israeli activists have advocated for the destruction of the Al-Aqsa compound to make way for a Third Jewish Temple.

In 1982, Jewish American-Israeli Alan Goodman, who had links to the violent pro-settler Kach movement, entered the compound with an automatic rifle and fired indiscriminately inside the Dome of the Rock, killing two Palestinians and wounding nine others.

In 1990, an Israeli group known as the “Temple Mount Faithful” entered the compound and attempted to place a cornerstone for the Third Jewish Temple, sparking confrontations between Palestinians and Israeli forces. The latter used live ammunition, killing more than 20 Palestinians and wounding at least 150.

Six years later, the Israeli government authorised the opening of a tunnel to the Western Wall, under the foundations of the Al-Aqsa Mosque Compound. Ever since, Israel has been sponsoring archaeological digs in the vicinity of the mosque operated by Jewish settler groups.

Amid an atmosphere of bubbling anger and a failed peace process, late politician Ariel Sharon’s visit to the Al-Aqsa compound in 2000 unleashed the Second Intifada. The uprising, also known as the Al-Aqsa Intifada, lasted five years and led to the killing of more than 3,200 Palestinians and 1,000 Israelis.

In this context, and with the backdrop of dozens of settlers entering the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound on a daily basis under the protection of soldiers, Palestinians believe they have cause for worry.

More recently, the 2017 order to indefinitely close al-Rahmeh Gate came only a few months after a popular Palestinian uprising against the installation of metal detectors and surveillance cameras at the entrance to the nearby Lion’s Gate.

Israel installed the cameras and turnstiles after a deadly gun battle on 14 July in the courtyards of Al-Aqsa Mosque, in which three Palestinian citizens of Israel shot and killed two Israeli policemen before being themselves shot dead.

For weeks, thousands refused to enter the compound and resorted to praying on the streets of the Old City in a protest of civil disobedience.

Israeli forces later removed the cameras and metal detectors - a success in the eyes of many Palestinians.

‘Inevitable’ escalation?

Khadija Khweiss, a prominent activist from Jerusalem, believes the al-Rahmeh Gate developments are just another sign of Israel trying to impose its hegemony on the site.

“We fear that Israel is trying to use al-Rahmeh Gate to turn into an access point for settlers to raid Al-Aqsa Mosque compound in the long run,” Khweiss told MEE.

“Israel is on the side of the settlers, and we are afraid that they will be able to exploit their government to achieve their goal of dividing Al-Aqsa,” she added.

Israel imposes restrictions on which Palestinians can and cannot enter the compound.

Israeli limits Palestinian entry to the site through its separation wall, which has cut off the occupied West Bank from Jerusalem.

Of the more than three million Palestinians in the occupied West Bank, only those over a certain age limit are allowed access to Jerusalem on Fridays, while others must apply for a hard-to-obtain permit to enter.

Meanwhile, Israeli settlers and religious activists have increasingly been able to enter the compound, as restrictions on non-Muslim prayers at Al-Aqsa have been significantly less enforced by Israeli forces.

On Thursday, Palestinian media reported that more than 100 Israeli settlers entered the Al-Aqsa compound under military protection, with some performing prayers near al-Rahmeh.

“If we’re comparing 2015 with 2018, you will find a huge difference in the way that Israeli police deals with settlers wanting to enter Al-Aqsa mosque compound,” said Qawasmi, the journalist from Jerusalem.

“In the past, the Israeli police would allow groups of at most 10 people at a time. Today, groups of at least 25 settlers come in because they feel secure,” she continued. “The Waqf guards used to be able to object and have some control over the situation, but today they get threatened by the Israelis.”

In the past few years, Waqf guards have regularly been arrested by Israeli forces for confronting settler groups at Al-Aqsa - with many of them receiving temporary bans on returning to the religious site.

Ibhais, the Jerusalem-based researcher, said he believes it is not long before matters flare up once more.

“As long as the occupation intends to change the status quo and impose its control over Al-Aqsa, things will inevitably escalate. And as long as al-Rahmeh Gate remains closed, the situation will escalate, whether now or later.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.