Coronavirus in Libya: The doctor battling war wounds amid outbreak

Nine years of civil conflict and governmental neglect have left Libya’s healthcare system in a state of near-collapse - so newly qualified doctor Mohammed* knew his first job, working in the trauma ward of one of Tripoli’s main hospitals, would be tough.

But, within months, another civil war for control of the capital broke out between Libya’s rival governments and the doctor, 28, found himself treating war-wounded civilians and fighters.

Then, a month ago, he was thrust onto another medical frontline, when Libya announced its first case of the coronavirus.

“I’ve been present three times when we’ve received suspected Covid-19 patients and, each time, it’s the same - chaos!” Dr Mohammed told MEE.

“Most medical staff have no training about infectious diseases so everyone panics and, because no-one knows what to do, everyone takes a guess, doing what he or she thinks is right.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

"Many nurses just walk out, saying they have no protective equipment or clothing and don’t want to get sick because of their families. And I can’t blame them, because it’s true.”

'If it's someone’s birthday, I’ll get them a mask'

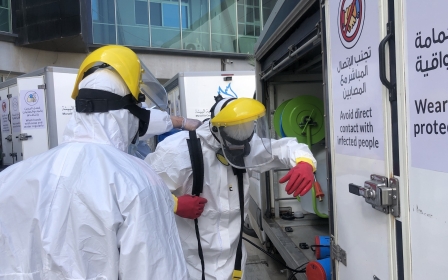

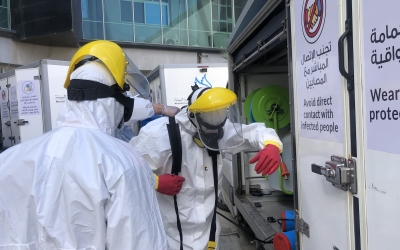

Shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) are a major concern among medical staff during this global pandemic and are particularly acute in war-ravaged Libya.

Surgical gowns and caps, along with basic medical masks and shoe coverings, are provided by Dr Mohammed’s hospital, but not N95 masks, goggles, face-shields or protective overalls.

He has his own N95 mask (which filters out 95 percent of airborne particles), overalls and face shield which he carries to work in his bag.

Some of these items Dr Mohammed bought himself, others were gifts.

“If it’s someone’s birthday, I’ll get them a N95 mask,” he said, laughing, “That’s the way it is now.”

Even disposable gloves are in short supply. Before Covid-19, boxes of these were readily available throughout the hospital but, since the virus reached Libya, they have vanished. Staff suspect many were stolen.

Masks, also in short supply, are now distributed daily to medics by a senior hospital official, a task deemed so important that, for three weeks, it was undertaken by the manager himself.

Medical aid sent to Libya from the UN, China and Italy has yet to trickle down to frontline medical personnel at Tripoli’s main hospitals.

Dr Mohammed has seen no evidence of any such new supplies, and said that existing supplies continued to dwindle.

'A big charade for the media'

Dr Mohammed's hospital treated Libya's “Patient Zero”, a 73-year-old man who was the country’s first known coronavirus patient, and who made a full recovery without the need for oxygen or a ventilator.

“Because he was Patient Zero, the authorities made a big charade for the media, but it was not a good show," said Dr Mohammed.

"The minister of health [Ehmed Ben Omar] and the hospital manager were wearing full protective suits by the patient’s bedside, but the doctors were just wearing their uniforms and basic face masks.

“The patient was not wearing a mask at all and was lying on a bed without sheets. It was terrible, like a joke, except that it wasn’t funny.”

Although the Tripoli-based, UN-backed Government of National Accord (GNA) has launched social media and TV campaigns to ensure civilians know which designated Tripoli clinics they should attend if suffering from suspected coronavirus symptoms, Dr Mohammed’s hospital continues to receive occasional cases.

'No policies or protocols'

Moreover, despite having cared for Patient Zero, the hospital still has no policies in place for dealing with Covid-19 cases.

“Someone thinking he may have coronavirus who came here would walk in through any door, as there is no triage area, and, because there are no signs, he wouldn’t know where to go, so would have to ask," Dr Mohammed explained.

"He would then wander around the hospital looking for a doctor himself and, eventually, when he found one, he’d be told to go to one of the clinics assigned for Covid-19 cases. But, if he did have coronavirus, he could have spread it all around the hospital, just because we have no policies or protocols.”

The total number of confirmed coronavirus cases has reached 61, with two deaths and 18 patients having recovered, according to Libya’s National Centre for Disease Control.

Stephanie Turco Williams, the head of the UN's mission in Libya, warned last week that intensified shelling, combined with the Covid-19 pandemic, risked overwhelming the country’s already decimated health system.

The war-wounded

Tripoli’s ongoing civil war has already resulted in hundreds of civilian casualties.

With one of the capital’s two largest trauma wards, many injured civilians are brought to Dr Mohammed’s hospital, but new shortages, sparked by the coronavirus, have left staff even less-equipped to treat them.

“I face dealing with trauma cases, often with severe ongoing bleeding, without gloves,” Dr Mohammed said.

'I sometimes have to make a big scene and threaten to walk out, just to get a pair of gloves, which are one of the most basic needs, especially in trauma'

- Dr Mohammed

“I sometimes have to make a big scene and threaten to walk out, just to get a pair of gloves, which are one of the most basic needs, especially in trauma.”

It’s not just PPE which is in short supply. The emergency room has no sterile gauze dressings (although these are available in other wards) so, following emergency procedures undertaken in the resuscitation room, patients have a high risk of infection.

Surgical teams work in an operating theatre with insufficient lamps and no ventilation, and complain of limited supplies, including stitch types and sizes.

“Sometimes I’d like to use smaller stitches to make scars less noticeable, or fancier stitches to reduce irritation to the body, but we can’t be picky here, we just have to use what there is,” said Dr Mohammed.

'Surgeons took turns pouring water'

In a 2017 report, the World Health Organisation (WHO) said Libya’s historically under-capacitated system had “further deteriorated due to fragmented governance, limited financial resources, deficient human resources, acute shortage of lifesaving medicines and basic equipment [and] a debilitated primary healthcare network”.

Even running water is sometimes scarce. Earlier this month, southern tribes cut Tripoli’s main water supply from the Great Man Made River in an ongoing dispute with the GNA.

Although, in such scenarios, the hospital has back-up water wells, the trauma ward’s tank ran dry one night, after no-one had thought to refill it.

“We had emergency operations, so surgeons took turns pouring water from five-litre bottles into the sink, so the other one could scrub-up before going into theatre,” Dr Mohammed said.

“And problems like these are just the result of disorganisation.”

The anaesthesia team is also constantly struggling, with limited oxygen supplies and a mechanical ventilator which frequently breaks down.

Staff threatened at gunpoint

“These are very frustrating working conditions, which affect both the speed and quality of your work," said Dr Mohammed.

"It’s not about being able to save lives, because I’ll still save the life, but often it won’t be as fast or as well done as I would like, and patients have a higher risk of infection and complications.

“But what I’ve learned working here is that a lack of equipment doesn’t stop you from doing your job." Dr Mohammed says the absence of equipment and drugs means that staff must respond to challenges by quick-thinking, adapting and improvising, known as 'System D'. "We rely on ‘System D’, doing what we can with what we have.”

Most seriously injured fighters from the frontlines are transferred for treatment outside Libya - testament to how little confidence the country’s healthcare system inspires.

But the trauma ward still receives battlefield casualties when field hospitals are full, and treating patients from armed factions in a country overrun with weapons carries additional risks.

Last week, when a GNA-aligned fighter was being treated for a gunshot wound, a fellow fighter, unhappy with the treatment, pulled out his gun, cocked it, and started threatening medical staff, almost forcing the hospital to close.

The Tripoli battle’s frontlines have not yet reached this hospital, but other medical facilities in the capital have been hit by shelling.

Although no-one feels safe in the capital these days, Dr Mohammed said his hospital continued to do its best for patients, under the most challenging circumstances.

Zero psychological support

“I’ve seen a lot of blood and treated severe injuries in my short experience, but treating a child is on a different level, especially if the child is very young and has been injured by shelling,” Dr Mohammed said.

He spoke about a recent night shift, where several children were brought in at the same time after shelling hit their Tripoli homes, and he had to make the agonising decision which child to treat first.

One was an injured two-year-old girl, in a state of shock and non-responsive, until she saw her mother. For days afterwards, he said, he could see her shocked, blank face, replaying in his mind.

Self-aware enough to know the potential psychological impact of his work, Dr Mohammed self-diagnosed himself with PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) a few months into the Tripoli war.

But medical staff receive no psychological training or support and, despite the hospital having a psychology department, to which ironically he can refer patients, Dr Mohammed doesn’t personally feel able to seek help there.

Instead, he relies on a small network of young medics working in trauma wards across the capital, who act as an informal support group for one another, sharing stories, frustrations, personal sadnesses and traumatic experiences.

“This means I don’t feel alone,” he explained. “Maybe I’ve got used to this lifestyle now, and have managed to find some balance because I’m doing okay, although it does worry me how I’ve lost interest in ‘normal’ stuff, where everything other than work seems trivial.”

Good training for the future

Despite having a government contract, Dr Mohammed is ostensibly working for free.

Some colleagues have not been paid for two years and, he says, he is not expecting to receive his backdated salary for three years, and perhaps not at all.

“Because I have an official contract, I do expect I’ll get paid in the future, but maybe I’ll never get paid," he said.

"But this is the reality and we know how it is. Many of us do this work for practice and experience.”

Those planning to work in private clinics, and anticipating lucrative future incomes, view working in Libya’s overstretched and underfunded public healthcare sector as an investment, but Dr Mohammed remains fully committed to public healthcare.

He nurtures a quiet ambition to one day work for Britain’s NHS, or international medical NGO Doctors Without Borders (MSF), gaining knowledge he can take back to Libya.

Dr Mohammed hopes treating trauma patients with limited facilities in Libya’s hospitals will serve as good training for the future, where he may be up against candidates with medical degrees more widely respected than Libya’s.

“Because I have this goal, I tolerate this very bad environment here, to learn on the job and gain experience because I know, in the future, if I try to work abroad, others will have studied in better medical schools than we have in Libya, so I hope my experience will help me,” Dr Mohammed said.

“And it can be very rewarding, providing healthcare in shitty situations. I can’t describe it exactly, but it makes me want to keep doing it, as a career.”

*Dr Mohammed spoke to MEE on condition of anonymity

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.