Sudanese stranded by coronavirus seek smugglers to return home

The closure of the Sudanese-Egyptian border has not deterred thousands of people stranded outside Sudan from smuggling their way home, as residents of border areas fear the breach will precipitate the spread of coronavirus.

Abdul-Aziz Ahmed, a gold miner working on the Sudanese-Egyptian border, told Middle East Eye that he was smuggled into Sudan in March and made his way to his village in Northern state unhindered.

The 32-year-old said that since the outbreak of coronavirus in the region, the trade of people-smuggling between Sudan and Egypt has significantly increased.

But what’s taking place between the two countries is not an exceptional case for Sudan’s wide and soft borders with seven other African countries.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Illegal crossings have become another shortcoming of the Sudanese government's fight against Covid-19, with people taking advantage of the country’s inability to control its sprawling border as it faces economic hardship and instability.

Multiple sources disclosed to MEE that thousands of Sudanese, foreign traders and gold miners from Egypt, Libya, Chad, Central African Republic and South Sudan are entering Sudan on a daily base without any restrictions, using different kinds of smuggling and illegal means.

Egypt

However, the border between Egypt and Sudan is considered to be the hotspot for illegal entry as thousands of Sudanese who had been in Egypt, mainly Cairo, for medical treatment, trade and other reasons are looking to come back home.

Helmy Hussein, a Sudanese stranded in the city of Sebaiya in the border governorate of Aswan, told MEE that he and hundred others have been stuck without assistance and have run out of money and food.

“We are around 1,200 Sudanese who planned to cross the border but the authorities have agreed to close the land border, and now we are stuck here.

'We need to go back home'

- Helmy Hussein, stranded Sudanese

“Most of the families were on short-term visits to Egypt, so they don’t have enough reserves of money and the situation is getting worse,” he said.

Hussein said that Sudan’s embassy in Egypt has helped some stranded Sudanese with accommodation but the ability to buy food and other necessities is still a challenge.

“We need to go back home,” he pleaded.

“We know that there are smugglers that help people cross but we don’t have enough money to pay for that.”

Furthermore, Sudan’s embassy in Cairo closed down after hundreds of stranded nationals attacked the building at the beginning of April, calling on the Sudanese government, headed by Abdalla Hamdok, to intervene and return them home.

However, residents of border areas have rejected the pleas of their compatriots, urging the government to continue closing the border to protect the people living around the frontier, activist Wael Alemam told MEE.

“All the citizens of the border areas are rejecting the opening of the borders that will put us on the front line of the negative impacts of such a move, seeing that corona can spread among us,” said Alemam, who hails from the settlement of Delgo in the Mahas region of Sudan’s Northern province, located near the border.

Fear in border towns

The Red Sea state, which has long borders with Egypt, has also witnessed many people smuggled into the state via crossing points, through the desert or by sea, a medical source and activists told MEE.

Abdul Rahman Mukhtar, an activist from Port Sudan, the capital of Red Sea state, said that thousands of people have come in through the crossing points of Gabatit, Shalateen and Halayeb without any screening or medical checks.

“The people-smuggling business has recently flourished throughout areas in the Red Sea state, especially after the closure of the borders,” he said.

An eyewitness from the coastal city of Ouseif near the border with Egypt also confirmed that dozens of people have entered the area illegally either by boats or land vehicles.

“People in our city are fearful of getting infected with Covid-19 because of these smuggling activities,” he said, wishing not to be named.

Meanwhile, a medical source, who spoke on condition of anonymity because he was not authorised to talk to the media, disclosed to MEE that nearly 70 suspected coronavirus cases were recently registered in Red Sea state as a result of people coming from outside Sudan.

“Red Sea state is one of the most exposed areas in Sudan because it’s by the sea and its border is long,” he said.

“Health authorities have put in place measures such as opening some isolation centres in Port Sudan and other areas, but they are facing real challenges to contain the disease.”

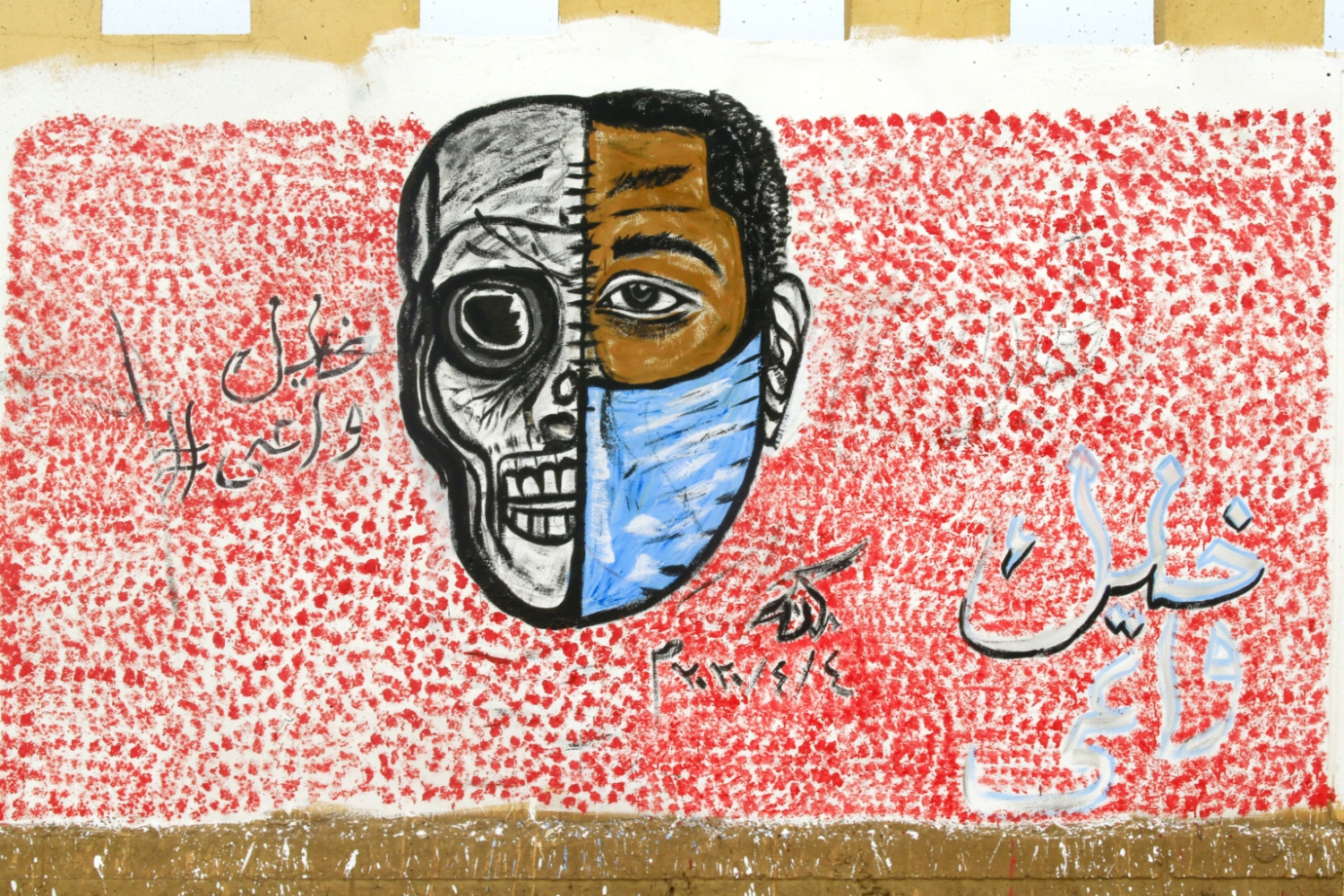

The capacities of these isolation centres, in terms of beds, medical staff, surgical masks and other personal protective equipment, are still very weak.

Darfur

The situation in the Greater Darfur Region, which borders Egypt, Libya, Chad, Central African Republic (CAR) and South Sudan, is even worse, with people, particularly gold miners and traders, crossing freely.

The health director of the South Darfur state, which has long borders with CAR, Chad, and South Sudan, said that thousands of people are moving through the borders every day.

“I can even say that the border crossings are easy to traverse daily…We have three crossing points…so the number of people crossing, both Sudanese and foreigners, is big”, Mohammed Idriss told MEE over the phone.

“The authorities have closed the border but it’s very long, so it is difficult to control,” he said, adding that this will have a major impact on the spread of the coronavirus, “because those crossing are doing so illegally and without medical checks.”

An official in West Darfur state, who wished not to be named, told MEE that El Geneina, the capital of West Darfur, has long been a centre for medical patients coming from neighbouring Chad and countries beyond, such as Mali and Niger.

“Thousands of patients suffering from different illnesses normally cross the borders with their families looking for medical care in West Darfur hospitals,” he said.

But with the spread of coronavirus, that trend has stopped.

“The security organs, the military and police have to double their efforts to control the border…Sudan’s health system is fragile and can’t bear any more burdens coming across the border,” the official said.

Historic free movement

Sudanese environmental expert Mohammed Salah said that the free movement of people across in Africa in general and particularly in Sudan is historic and has a lot of positive and negative impacts.

'These borders were created by colonialism. Normal people have nothing to do with it, they don’t recognise them'

- Mohammed Salah, environmental expert

He said the natural interstate crossing has played the role of a cultural bridge between the continent’s countries and allowed mutual trade, but it has also allowed the movements of terrorist groups, money launderers, human traffickers and other criminal groups.

“These borders were created by colonialism. Normal people have nothing to do with it, they don’t recognise them and so they go about their activities normally,” Salah explained.

However, he added, the current uninterrupted movement cannot be allowed to continue or at least needs to be organised during these critical times.

“Since these movements are socially rooted by the grassroots, stopping them may face resistance because of the impact that would bring on people’s interests,” Salah warned.

“The authorities need to deal with the issue very wisely and without the use of violence, and the local community leaders can play a very positive role in this regard.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.