'Killed our motivation to live': Syrians left heartbroken as they face deportation from Denmark

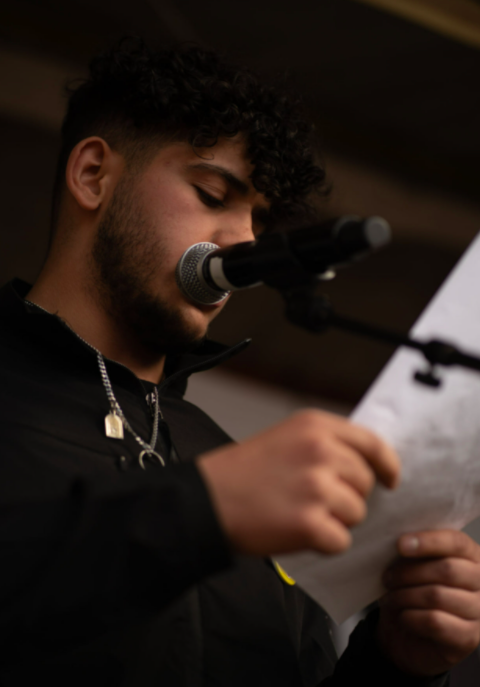

The first thing Mohamed Alata does each day when he comes home from school in the Danish town of Vejle is check the mailbox.

Ruffling through the post one day this March, the 18-year-old Syrian refugee found a letter from the Danish Refugee Board addressed to his mother, Sabriah Hassan al-Fayed.

Alata then knocked on her bedroom door, opened the letter and read it out aloud, hoping for good news.

But as he scanned the page he realised, horrified, that Denmark had refused to renew Fayed's residency. She could be deported in 30 days with his two younger sisters.

"Our future was completely changed by that letter," Alata told MEE.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

For years, Denmark has been a refuge for the family who were living in a town on the outskirts of the Syrian capital Damascus when the war started in 2011.

In 2012, Alata's father was killed by a Syrian government sniper. Three years later, Alata and his older brother fled for Denmark after they refused to serve in the army.

A year later, after the Syrian government killed her brothers, Alata's mother followed with his two sisters.

"We fled from a country where a war was raging, but we didn't just flee from the war," he added. "Assad's regime is the main reason we fled."

But now the prospect of his mother's forced return to Syria haunts him every day. He fears she will be arrested and tortured by Syrian government forces.

"The Danish government choosing to split a family is simply not humane," said Alata, whose mother suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder caused by the civil war.

"I know if my mum is sent back to Syria, they will ask her about me and my brother and why we refused to serve in the army. She could be sent to prison and tortured there.

"My two little sisters are so attached to Denmark. They can't read or write in Arabic. They speak fluent Danish. It would be so difficult for them in Syria."

His family's plight mirrors hundreds of other Syrians in Denmark who are being threatened with possible deportation to Syria.

'Zero refugee' policy

In 1951, Denmark was the first country in the world to sign up for the UN Convention on Refugees and has traditionally been a supporter of refugee rights, according to the international body.

At the height of the European refugee crisis in 2015, Denmark took in 21,000 refugees who reached its border.

But during the same year, Danish authorities tightened restrictions on refugees entering the country and earlier this year, Denmark became the first European country to publicly declare its intention to send Syrians back to government-held areas inside the country.

Deeming Damascus and its surrounding areas safe, the Danish government has sent out notices to at least 390 Syrians who have had their residency permit renewals denied or revoked and now await a final decision by the Danish Refugee Appeals Board.

The move is part of a series of new laws introduced by Danish legislators who aim to have zero asylum-seekers and appear tough on immigration, reversing the country's once liberal approach to refugees and support for their integration.

"If you want to track this change in policy, you have to go back 20 years and look at how Denmark's centre-right parties dominated the conversation on migration in the early 2000s," explains Amani Hassani, a sociologist at Keele University who researches Denmark's immigration policies.

"And for the Social Democrat Party in Denmark to compete, they have shifted their policies to this point of view in order to win votes, especially when they are competing with parties who are solely focused on dominating the migration conversation.

"It left the small left-wing parties in the lurch with major political players in Denmark competing to be more right-wing."

Alysia Grapek, a refugee activist in Denmark, echoes Hassani's concerns that the Danish government is "racing to reach their goal of having zero asylum seekers".

"By removing asylum protections for some Syrian refugees, they are sending a message that refugees are not welcome and trying to discourage other asylum seekers from coming to Denmark," Grapek told MEE.

Possible torture and imprisonment

So far, no Syrians have been sent back.

But at least 39 Syrians who had sought refuge in Denmark have already received a final decision and been placed in "return centres", where they are not allowed to work or pursue an education.

It remains unclear when they will be sent back to Syria as the Danish government has yet to decide how to send people back to the active war zone.

But the fear of being sent back fills many of the 35,000 Syrian refugees who have made Denmark their new home with dread.

Asmaa al-Natour, a Syrian refugee who lives in Copenhagen, came to Denmark in 2014 with her husband and son.

She describes having a normal life in Denmark. She learns Danish, works a full-time job, pays taxes and socialises with Danish friends and neighbours.

Natour is from Daraa, where the Syrian revolution began and was active in organising protests to oust President Bashar al-Assad in the early years of the civil war.

If taken back, Natour could face arrest and torture.

"We just received the last decision that we only have up to 30 days to leave Denmark, or else we will be sent back to Syria or put in deportation centres, all because they believe that Damascus is safe under Bashar al-Assad," said Natour whose family received their final notice this month.

"They have killed our motivation to keep living in this life. I am so scared for my husband and I am scared for my children."

Yet despite the imminent deportation threats, hundreds of Syrians and refugee activists have staged a sit-in outside Denmark's parliament by locking hands and refusing to leave.

Last month, the "red hearts protests", backed by Amnesty International, took place in Copenhagen and 24 other cities and towns following the government's decision to withdraw residency permits from some Syrian refugees.

Grapek, the refugee activist, notes the growing number of Danes attending the protests after learning how dangerous repatriation could be for Syrian refugees.

The situation has forced some refugees to relocate to a third country in the hope of not going back to Syria where they could face persecution. Fawzi Hasan is one of them.

In April, Hasan received a letter from the Danish Refugee Board that it would be reassessing his case.

Originally from Damascus like many others who received deportation notices, Hasan was given 30 days' notice in April 2021 of possible deportation after his case was "reassessed" by Denmark despite previously receiving residency papers.

But instead of waiting to be taken to the return centre, he made the decision to take his family to Germany in the hope of living in safety, leaving behind his 24-year-old son, Mahmoud.

"We are scared and worried and we feel uncertain all the time about what the future holds," Mahmoud Hasan told MEE.

"We have nothing left in Syria. No house, no work, absolutely nothing. That's why they went to Germany and I am in Denmark alone. They asked me to go with them but I said no because I want to stay and continue my studies."

For now, Syrians in Denmark are left in limbo and unsure of what the future will hold.

Earlier this month, Copenhagen passed a bill paving the way for the transfer of asylum seekers and refugees to a third country outside of Europe. With a newly inked migration agreement between Denmark and Rwanda, human rights advocates have warned that refugees may be sent there.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.