The terror list Egypt uses to terrorise its citizens

On Egypt's "terrorism list" lie over 6,300 names, among them some of the most fierce and dangerous militants alive today.

Those men are just a small fraction of the register, however, named alongside hundreds of peaceful activists, politicians and human rights lawyers, or simply people related to them.

Rather than fighting terror, its detractors say, the Egyptian government is using its swelling terrorism list to crush any opposition and independent thought, intimidating critics and their relatives into silence.

'I feel like I am in prison. My life has been all the more complicated because I cannot travel to see my husband, who works abroad'

- Egypt businesswoman on terror list

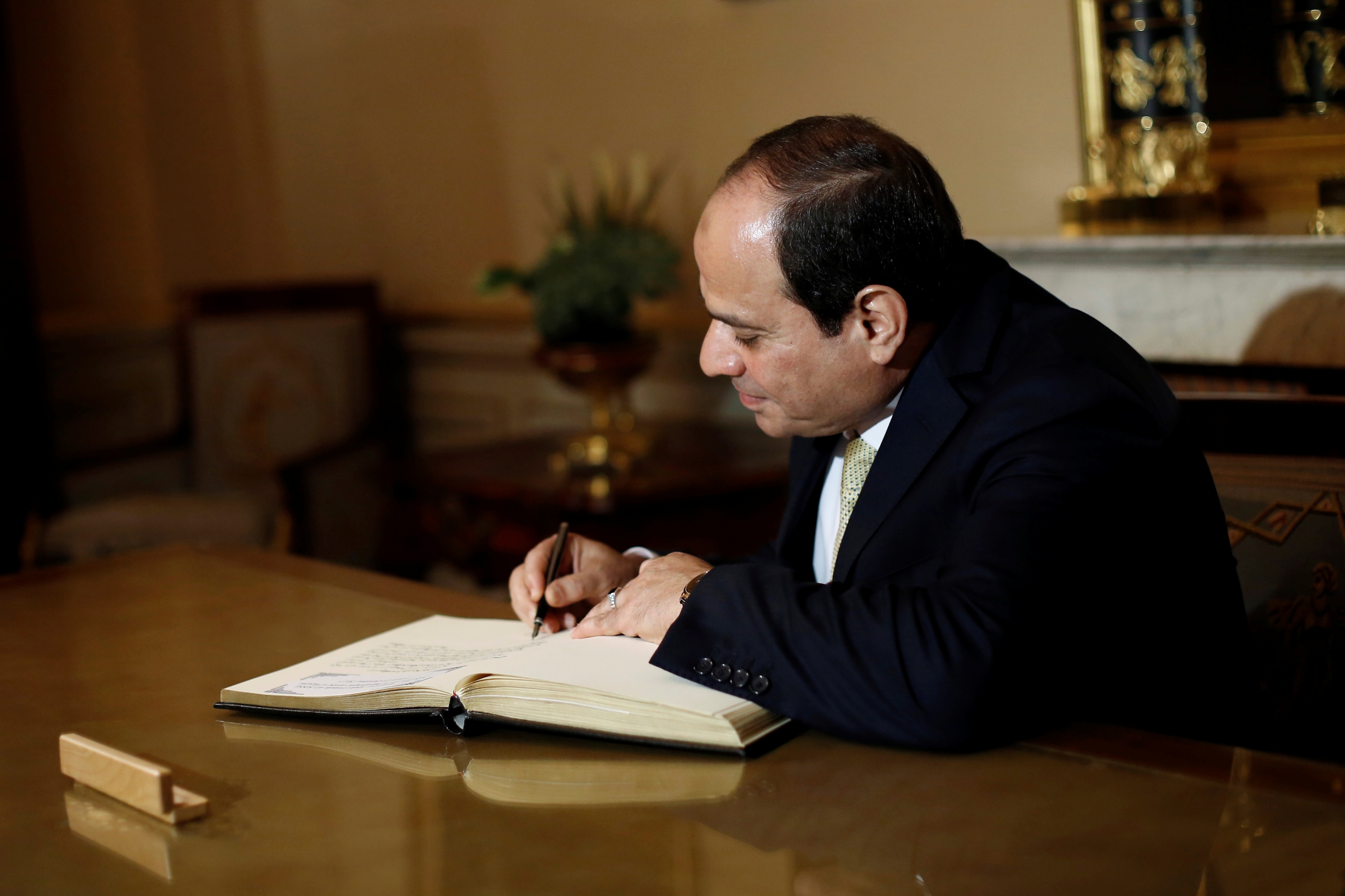

President Abdel Fatteh el-Sisi, who justifies his authoritarian rule with the perceived threat of militant groups, has relied heavily on counterterrorism laws as a legal basis for targeting members of the opposition.

Among those is the highly controversial "law organising the lists of terrorists and terrorist entities", which came into effect in February 2015 and was last month strengthened by Sisi with new amendments.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The process of being placed on the list is both swift and opaque. Public prosecutors propose additions, a court then has seven days to rule on that suggestion, and the person affected then has 60 days to appeal once the decision has been published.

From then, the newly designated terrorist threat can then be handed a travel ban, see their passports confiscated or cancelled, and have their financial assets frozen.

Vaguely worded and broadly open to interpretation, authorities quickly began designating activists and opposition politicians as terrorists, much to the horror of human rights groups.

Offences undefined by the law include: “Infringing the public order; endangering the safety, interests, or security of society; obstructing provisions of the constitution and law; or harming national unity, social peace, or national security.”

Egypt's law organising the lists of terrorists and terrorist entities

+ Show - HideKey dates

December 2014: A bill is approved by the cabinet, in the absence of a sitting parliament.

17 February 2015: The law, known as law no. 8 for the year 2015, is ratified by President Abdel Fatteh el-Sisi and published in the official gazette.

January 2016: The law is retroactively approved by parliament.

3 March 2020: Amendments are ratified by Sisi and published in the official gazette.

Consequences of the law

The law allows the public prosecution to name individuals or entities to be designated in a terrorism list.

The designation can be based on a court verdict, or a request by the prosecution.

The request is then referred to a criminal judicial circuit in the Cairo appeals court. A designation is confirmed within seven days.

Those who wish to challenge the designation must do so within 60 days of the decision.

The Court of Cassation, Egypt’s highest appeals court, reviews the challenges and makes a decision within seven days.

Those placed on the list can then be banned from travel, have their passports confiscated or cancelled, and have their financial assets frozen.

Human rights groups have condemned vague wording in the law that allows authorities to designate peaceful activists as terrorists.

Broad offences undefined by the law include: “Infringing the public order; endangering the safety, interests, or security of society; obstructing provisions of the constitution and law; or harming national unity, social peace, or national security.”

Amendments

The latest amendments to the law were ratified by Sisi and published in the official gazette on 3 March, and expand the criteria and penalties introduced in the previous version of the law.

For example, they allow authorities to freeze assets without them being linked to terrorism-related activities.

They also bar the designated individuals from membership of any professional or government entities, as well as syndicates, and disqualifies them from any political activity.

The amendments also eliminated any loopholes that were used by the Court of Cassation to reject the designations.

The amendments passed in March expand the criteria and penalties, allowing authorities to freeze suspects' assets without needing to tie them to terrorism-related activity.

They also bar the designated individuals from membership of any professional or government organisations, as well as unions, and disqualifies them from political activity.

The amendments also eliminated any loopholes that were previously used by the Court of Cassation, Egypt's highest appeals court, to reject the designations.

Those added to the lists since 2015 include deposed president Mohamed Morsi, footballer Mohamed Abu Trika, businessman Safwan Thabet, former presidential candidate Abdelmoneim Aboul Fotouh, journalist Hisham Gaafar, and, most recently, former MP Zyad el-Elaimy and Egyptian-Palestinian activist Ramy Shaath.

'It's been 290 days since I saw and talked to my husband, and making this injustice worse by this decision is inhuman and cruel'

- Celine Lebrun-Shaath

The latest additions to the list, announced on 18 April, accused Shaath, Elaimy and 11 other political dissidents of collaborating with the outlawed Muslim Brotherhood group, from which Morsi hailed, to carry out activities against the state.

Their lawyer, Khaled Ali, has said that the decision was taken in his absence, but that it would be appealed.

Celine Lebrun-Shaath, Shaath’s wife, said she viewed the decision as “politically motivated”.

“It is a shabby attempt to tarnish their reputation,” she told Middle East Eye.

Shaath, 49, was a founding member of the liberal al-Dostour Party, following the 2011 revolution. Since the summer of 2014, his political activities have been focused on establishing and coordinating the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) pro-Palestinian movement in Egypt, his wife said.

Elaimy, meanwhile, is a human rights lawyer and one of the youth leaders of the 2011 pro-democracy revolution.

Both activists were arrested last summer in a crackdown that targeted several other secular opposition politicians who had convened to plan for a political alliance called the Hope Coalition that would run in November's upcoming parliamentary elections.

Elaimy’s mother, Ekram Youssef, said in a Facebook post on Wednesday that the terrorist designation is likely an attempt to disqualify her son from taking part in the elections, as he is set to be released from prison in June.

“You have made us a laughing stock in front of the world, and no one will believe your terrorism story anymore,” she said, addressing the Egyptian state.

A law 'with political motives'

Hussein Bayoumi, Egypt researcher at Amnesty International, said the terrorism designation has been used unjustly, mainly because those placed on the list have no chance to defend themselves until the appeals stage.

And, despite the fact that the Court of Cassation has reversed some of the designations due to the absence of investigations, the new amendments to the law now make it legal to place people on the list without a shred of evidence of any terrorist activity, he told MEE.

Alaa Abdelmonsef, an Egyptian human rights lawyer, said that the terrorism list law was primarily passed “with political motives”.

“It is a political law that has nothing to do with the constitution,” he told MEE.

“Designating an individual, according to the law, is a matter the court can decide based on a recommendation from the general prosecution, without trial or investigations.

'The objective is to control political opponents by limiting their movement and controlling their financial assets'

- Alaa Abdelmonsef, human rights lawyer

“The objective is to control political opponents by limiting their movement and controlling their financial assets,” he added.

In many ways, Abdelmonsef said, the terrorist designation is worse than criminal convictions, because those placed on the list are often done so for tangental reasons and have no opportunity to defend themselves until the decision is published.

Not only does it severely restrict movement and cut people from their finances, it can be professionally and socially debilitating: membership of professional syndicates or leisure clubs is also lost.

In many cases, people have been added because they are related to someone deemed problematic by the government, or they have a professional connection to another person who is on the list.

“A significant number of those on the lists have been previously prosecuted in political cases, including the 13 people added on Saturday,” Abdelmonsef said.

“It is a tool for political retaliation,” he added. “Both the law and the judicial process are flawed.”

Families separated

Many of those on the list have no history of political activity, or have been added due to association with a family member on the list, according to several cases examined by MEE.

The designation has taken a heavy toll on those who have been banned from travel or whose assets have been frozen.

An Egyptian businesswoman, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said she was shocked to find her name placed on the list in 2017, and her life has completely changed since that day.

She believes her name was added because her father, a businessman, was perceived by the state to be supportive of Morsi, despite being a former member of a liberal party unaffiliated with the deposed president.

“My life has always been centred on my work, and I've never been engaged in any political activity,” she told MEE.

The young businesswoman said her company had since been seized by the military, and she currently works there as an employee of the armed forces.

“My passport was confiscated at Cairo airport on my way to one of my business trips,” she recalled.

“I feel like I am in prison. My life has been all the more complicated because I cannot travel to see my husband, who works abroad."

Another woman, an academic and former activist, said she has been unable to receive her university salary since designation in 2017.

“All my bank accounts have been frozen without any legal basis,” she told MEE.

“Since the ban, I haven’t been able to see my children or grandchildren, who live abroad. They are also afraid to visit Egypt because of the crackdown.”

Similarly, Lebrun-Shaath, a French national, told MEE that she is afraid she won't be able to see her husband for five years. She was forcibly deported from Egypt after his arrest in July 2019.

"This new decision prohibits Ramy from travelling for five years. If by some miracle he was released on parole, I would still be prevented from finding my husband,” she said.

"It's been 290 days since I saw and talked to my husband, and making this injustice worse by this decision is inhuman and cruel. "

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.