'We fell short,' Democrats mildly criticise decision to freeze some military aid to Egypt

A group of Democratic lawmakers have said the Biden administration's decision to withhold only a portion of military aid to Egypt "violates the spirit and intent of the law," as they took aim at the country's human rights record while trying to balance their criticism of the White House.

The Egypt Human Rights Caucus said in a statement made available to Middle East Eye that while the Biden administration had "rightly concluded the Egyptian government's human rights abuses are among the worst in the world," the White House had redefined the purpose of military aid in order to evade congressional requirements on the funding.

Egypt is the second-largest recipient of US military aid, receiving $1.3bn each year from Washington. In 2014, Congress began imposing human rights conditions on $300m of the military aid, but former presidents Barack Obama and Donald Trump both issued national security waivers to bypass the restrictions.

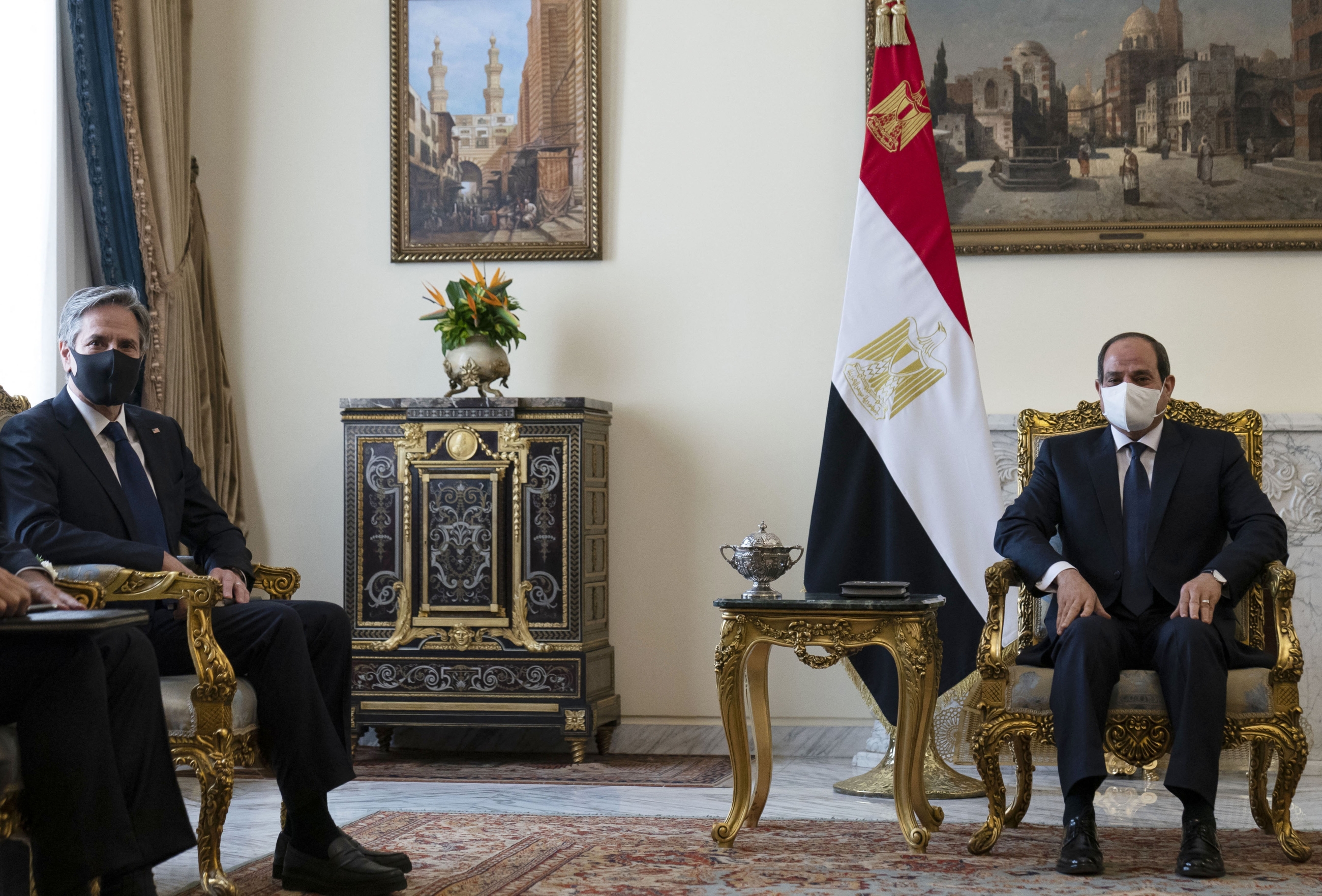

Last week, the Biden administration decided to withhold a portion of the $300m to Egypt this year - some $130m - agreeing to release the funds only if the government of President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi meets a set of human rights demands.

The decision not to issue a waiver and tie the $130m to progress on human rights was seen as a middle ground by the White House which has promised to put rights abuses and democracy at the forefront of its foreign policy.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

"While we commend the [Biden] administration for acknowledging Egypt's terrible human rights record - for not using a national security waiver, and for withholding some of Egypt's military aid - the decision ignored the clear intent of Congress that $300 million be held back, and sidestepped Congressionally mandated conditions on that aid," the statement said.

'Environment of impunity'

The Egypt Human Rights Caucus is among a growing list of voices within the Democratic Party which has grown critical of the US' relationship with Egypt.

Democratic Senator Chris Murphy, who chairs the foreign relations subcommittee on the Middle East was among one of the lawmakers calling for Biden to withhold the full $300m in aid.

"Withholding the $300 million of the $1.3 billion, until Egypt makes real concessions on reform, it won't fundamentally harm U.S. interests in the Middle East. It will only make us more safe," Murphy said this earlier summer on the Senate Floor.

In a statement issued last week, Murphy called the Biden administration's decision to hold only a fraction of the aid a "half-hearted," step.

"This was a chance to send a strong message about America's commitment to human rights and democracy, with little cost to our security, and we fell short," he said.

Since Sisi seized power in military coup in 2013, the space for political dissent in Egypt has shrivelled with nearly 60,000 political prisoners held in jails in the country.

The US State Department has documented cases of extrajudicial killings, torture, and forced disappearances. In a recent report, it said the Egyptian governments unwillingness to investigate human rights abuses has contributed "to an environment of impunity."

Lawmakers in the Egypt Human Rights Caucus said they "hope the administration's acknowledgment of the problem, and willingness to condition at least some aid, will spur a deeper debate about the value the American taxpayer and the Egyptian people get from gifting $1.3 billion in weaponry to Egypt's military-run regime."

Eye-catching number

For many lawmakers and rights groups, the $1.3bn military aid Cairo receives every year has been used to highlight much of what is wrong in the US-Egyptian relationship.

But many analysts say the situation is far more complex and the topic of US military assistance to Egypt, called Foreign Military Financing, or FMF, is not as clear as it seems.

"FMF is close to, if not our greatest source of leverage with Egypt," Grant Rumley, a senior fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy and former advisor to the Department of Defence told Middle East Eye.

"At the same time it's not really a good tool in terms of getting them [Egypt] to change their behaviour," he added.

This is in part because the US doesn't actually send $1.3bn to Egypt. Those funds are held by the US government in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Instead, an agency within the Department of Defence makes purchases from US defence contractors on behalf of Egypt using FMF funds.

"The money itself never leaves the US, the aid is like a payment to the defence industry," Rumley said.

Much of what the US buys for Egypt is long term assistance in the form of upgrading and maintaining equipment, or providing technical support. Purchases of large, new weapons systems usually come in instalments and can take years to fill.

The Biden administration's decision to withhold some aid also shows the opaque nature of the funding.

Middle East Eye reached out to a State Department spokesperson to ask what specific equipment would be withheld and was told the Biden administration was "making available $170 million in Fiscal Year 2020 FMF assistance for Egypt for border security, non-proliferation, and counterterrorism programs, consistent with the Department of State's appropriations act."

It's unclear exactly how this will effect future procurement. In the past Egypt has purchased attack helicopters as part of its counterterrorism operations in the Sinai and when previously announcing a shipment of F-16's to the country, the US Embassy said the fighter jets would provide "a new tool to help Egypt in its war on terrorism."

Rumley said the decision to withhold the $130m means Egypt will have to prioritise where it spends the money, ensuring the upkeep of old equipment will likely be first, but he did not think it was enough to shift their calculus on big purchases.

"It will send a message, but I don't see this as seriously hampering their abilities," he said.

Carrot and Stick

Whether that message has an effect on Sisi's desire to enact changes on human rights is also another matter.

In a first for the country, Sisi announced a new human rights strategy last week, issuing a 78-page document which calls for legal reforms to protect civil and political rights and for the training of state employees with the aim of instilling a sense of awareness and commitment to human rights within government institutions in the next five years.

Rights groups are sceptical of the plan. Reporters Without Borders said it "hopes this national programme for human rights will be something other than a joke in bad taste."

Mirette Mabrouk, a senior fellow and director of the Egypt program at the Middle East Institute in Washington, said "there is no getting around the fact that Egypt has a bad human rights record."

But she cautioned that attempting to pressure Cairo with aid may prove harder then some on Capitol Hill believe. "The stick part of the carrot and stick equation has never really worked well with Egypt," she told MEE.

"The Egyptians will not be happy about this decision [withholding aid], but they won't be distraught."

In the end, that may be what the Biden administration is hoping for.

Egypt has been a key Middle Eastern partner for the US going back to the 1970’s when President Anwar Sadat decided to establish diplomatic ties with Israel.

Following the tumultuous years of US-Egyptian relations under President Gamal Abdel Nasser, Sadat's Egypt was also viewed as a bulwark against communist expansion. Military aid was one way to keep it in the Western bloc.

Lawmakers on Capitol Hill who are looking to cut back on assistance are now calling the basis of those old ties into question.

"Because of various geo-strategic developments this relationship has changed" Mabrouk said, adding that "neither partner is as closely bound to each other as before."

Like old times

But for those looking to influence Egypt's domestic politics, this also means that the US' leverage is not as strong as it once was. In 1978, US aid to the country stood at six percent of its GDP, today that number is less then half a percent.

While US aid still makes up a sizable portion of Egypt's defence budget - at around 10 percent - other countries have been eager to increase their share of the market.

In recent years, Egypt has turned to France for large volumes of arms, including mistral-class helicopter carries and fighter jets. In May of this year its Defence Ministry confirmed an agreement to buy 30 Rafale fighter jets from France in what some estimates say is a $4.75bn arms deal.

Speaking at a joint press conference with Sisi last year, Macron told reporters: "I won't condition our co-operation in defence and economic matters on these disagreements [over human rights]."

While France is a NATO ally, Egypt has also shown its willingness to work with Washington's foes.

This year the country received its first batch of Su-35 fighter jets from Russia. Cairo went ahead with the deal even though the US warned it risked triggering sanctions with the purchase.

"Sisi has made a sustained effort to diversify Egypt's armaments. The country is not as reliant on the United States as it once was," Rumley said.

In 2018 Egypt also made drone purchases from China. Since launching its Belt and Road Initiative, Beijing has become a major investor in the country's economy setting up free zones along the Suez Canal and taking on massive infrastructure projects.

While some lawmakers say Washington’s policies vis-a-vis Egypt remain stuck in the past, others are concerned the US may risk losing its influence exactly at a time of rising great power competition.

Republican Senator Todd Young has warned that overly restricting arms sales to Middle Eastern countries could open up more space for China and Russia.

"As the United States reduces its own presence in the Middle East, our role in the region must change from the leader to an active supporter"” he said last month. "We will have to rely on governments of the partners and allies we have, not the ones we necessarily wish we have."

Rumbley said this may explain the Biden administration's attempt to find a middle ground on aid. "As the focus shifts elsewhere to China and Russia I don't think the administration wants to start torching its traditional partnerships."

Pick up the Phone

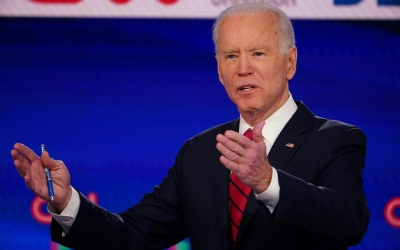

When entering office earlier this year, Biden initially gave the cold shoulder to Egypt, famously not calling his Egyptian counterpart for months. This was in stark contrast to Biden's warm relationship with previous Egyptian strongman Hosni Mubarak.

On the campaign trial Biden had pledged to put human rights at the centre of his approach to foreign policy and promised: "no more blank checks for Trump's favorite dictator."

But eventually Biden picked up the phone after Cairo helped negotiate a ceasefire between Hamas and Israel during the latest uptick in fighting in May.

Asked about the bilateral relationship, a State Department spokesperson told MEE that Egypt is a "valuable U.S. partner, particularly on regional security, counterterrorism, and trade." They said the decision to partially freeze aid, "reflects both our values and our interests.”

The most populous country in the Arab world and home to the Suez Canal through which 13 percent of global trade passes, Egypt's strategic location on the Mediterranean means it's not only a partner in counterterrorism, but crucial to stemming migration from Africa and the Middle East to Europe.

The Arab Spring threw the country into turmoil and Egypt's military-backed government focused on internal crisis while cementing its control at home.

But more recently it has begun to play a bigger regional role. It is shipping gas to Lebanon under a US brokered plan and has agreed to deepen security and economic cooperation with Iraq and the United States' steadfast-ally Jordan.

Rumley said encouraging Egypt to develop a closer relationship with other regional partners has been a priority for Washington. It also brings benefits to Cairo, which has its eye on lucrative reconstruction projects in Iraq and wants to establish itself as an energy hub in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Mabrouk said Egypt's foreign policy today was driven by its internal needs. "Egypt sees a lot of these issues as important to their own security and interests."

"They don't pursue good relations with Israel or an interest in Iraq's security because they receive FMF," she added.

Some see this as a reason to further reduce aid to Egypt. But the Biden administration appears to be hedging its bets.

"It's not this administration's approach to publicly criticise allies. I think their inclination is to work things out privately," Rumley said.

The Biden administration's willingness to take heat from many progressive groups and some lawmakers may in-part be seen as a reflection of Egypt's continued importance to Washington.

According to Mabrouk, "You hear a lot of analysts and some lawmakers talking about how Egypt is not important to the US, but you rarely hear people in the Defence Department or State Department saying that."

"You can't consider Middle East policy without considering Egypt," she added.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.