The Egypt-Israel gas deal: What's the chance it will go up in smoke?

TEL AVIV, Israel - There is selling ice to the eskimos. And sand to the Arabs. Now there's gas to Egypt.

The rush is on to finalise a deal which would see $15bn worth of Israeli gas supplied to a private Egyptian company during the next decade.

'At least on paper, there is no necessity for Israeli gas any more'

- Elai Rettig, Institute for National Security Studies and University of Haifa

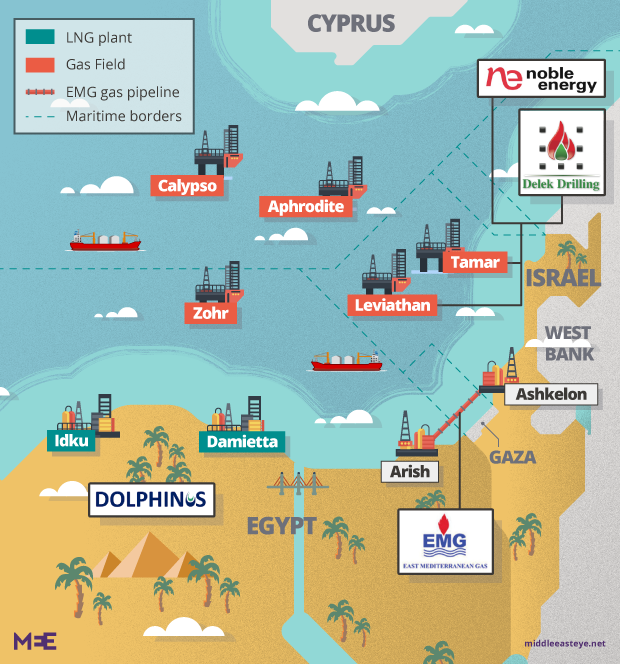

The agreement between Israeli company Delek Drilling and Texas-based Noble Energy, who are partners in Israel’s Tamar and Leviathan fields, and the private Egyptian company Dolphinus Holdings was first publicised in February.

As yachts passed by in Israel's Herzilya marina earlier this month, the deal continued to sail through as Delek shareholders voted to invest in a company controlling the only pipeline between Israel and Egypt.

One of the Delek shareholders who attended the meeting said a company representative told those gathered that, with control of the pipeline, gas could flow as quickly as the end of the year to Egypt - and so would their returns.

“We will see the money in a very short amount of time,” he said they were told.

The same parties announced a similar deal back in March 2015, at a time when Egyptian households and factories had been suffering regular blackouts as a result of energy shortages.

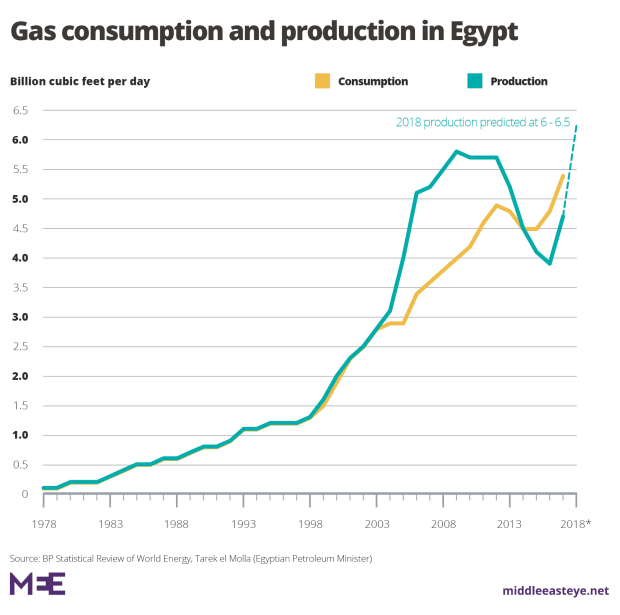

That deal never came to fruition. Three years later, the market in the gas-rich East Mediterranean – and globally – has transformed, leaving one pesky detail for Israeli gas dealers: Egypt is now nearly gas self-sufficient.

As Elai Rettig, a research fellow at the Tel Aviv-based Institute for National Security Studies and lecturer at the University of Haifa, puts it: “At least on paper, there is no necessity for Israeli gas any more."But there is every necessity for Israel to sell gas: the longer the gas sits unsold, the more gas will be discovered in the Mediterranean, and the more likely that Israel's dream of cost-efficient regional sales is postponed indefinitely.

But that is not what is said publicly. Israeli government reports have concentrated instead on arguments based on Israeli national security.

What's in it for Egypt?

Critically, the gas deal announced in February would allow Delek and Noble, and smaller partners in the field, to continue investing in Israel’s biggest gas field, the aptly named Leviathan, which has yet to produce any gas since it was discovered in 2010.

The companies have already invested $3.75bn in the first phase of Leviathan's development, which they called the largest energy project in Israel’s history. Industry observers expect the field to start producing next year.

The logic for Cairo is much less clear: once Egypt can satisfy its domestic needs – which could happen as early as 2019 - then Israeli gas, say analysts, will likely cost more than Egyptian gas simply because of the added costs of importing it.

The gas could still potentially be re-exported from two largely idle liquefaction plants in the Egyptian towns of Idku and Damietta, the only such facilities in the Eastern Mediterranean.That's the vision Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has for the country. When the deal was announced, he said Egypt had “scored a goal”.

“I’ve been dreaming of it for four years – that we become a regional hub for energy,” Sisi said. “All the gas coming from around the region will come to us.”

If this were to happen, then Egypt would profit from tolls and transit fees.

But there is also a widespread belief among industry observers that it won't be long before Egypt discovers even more gas, and will want to use the limited capacity of the LNG plants to export its own.

Given that the commercial basis of the current deal is unknown, it is unclear from which Egypt would profit more: exporting its own gas or re-exporting Israeli gas.

None of these details, however, has stopped the deal from moving forward. If anything, the clock is ticking as the companies selling Israeli gas attempt to push into one of the last viable local markets.

'The deal does not serve Egypt, nor its national security in any way. Does Egypt need natural gas? No, it doesn’t'

- Khaled Foad, Egyptian Institute for Studies

Meanwhile some Egyptians, such as political analyst and former geophysicist Khaled Foad, have been left shaking their heads.

“The deal does not serve Egypt, nor its national security in any way," said Foad, who is currently based at the Egyptian Institute for Studies in Istanbul. "Does Egypt need natural gas? No, it doesn’t."

The deal may be a private one, Foad said, but politicians continue to refer to the deal as one struck between the Egyptian and Israeli governments.

He underlined how Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has said that the money from the deal will be invested to improve health and education for Israelis.

“We need the same for Egypt,” said Foad. “We have lots of sectors that need development, but we are giving Israel a gift in exchange for minor gains.”

The murky history of Israeli-Egyptian gas deal

The deal is but the latest chapter in an East Mediterranean saga that has seen Israeli and Egyptian gas fortunes rise and fall, their fates murky and seemingly intertwined. It is also a saga which has, at various points, left both Israelis and Egyptians in the dark.

A decade ago, Egypt was a net exporter of gas, providing 40 percent of Israel’s natural gas at some of the lowest prices in the world.

The sweetheart deal was made between two state-run Egyptian companies and the Egyptian-based company East Mediterranean Gas (EMG), which formed in 2000 to build a pipeline between Egypt and Israel, and whose partners include former Israeli intelligence agent and energy tycoon Yossi Maiman. It drew criticism from Egyptians and fed into the uprisings which overthrew then-president Hosni Mubarak in 2011.

By 2013, Egypt had suffered years of political instability and energy sector mismanagement, including other questionable deals which MEE has investigated, as well as repeated attacks in the Sinai on the gas pipeline.

Egypt was unable to meet its domestic demand and honour its export contracts. Instead it began importing expensive liquid natural gas (LNG) for a rising population which was suffering from regular blackouts.

Israeli gas: Who will buy it?

Egypt fell into an energy-dependent slump - but the future for Israel, which had long imported its gas, was looking bright.

In 2009, Noble and Delek discovered the Tamar field, quickly followed in 2010 by Leviathan, one of the largest global discoveries this century.

Then minister of infrastructure, Uzi Landau, said the discovery was “the most important energy news since the founding of the state” and there was talk of Israel becoming the regional gas hub.

But in the years that have passed, companies have struggled to untangle a Gordian knot of political and economic problems relating to one issue: how to sell it.

In 2015, after energy companies had invested billions to discover the fields and waited years to produce gas, the Israeli government approved regulations to make the sector more competitive, a move that many believe frightened off foreign investors unsure what the government might do next.

Almost a decade after it was found, only Tamar has produced gas for commercial consumption. It currently supplies nearly all of Israel’s gas, but its only non-domestic customers are Jordan’s state-owned Arab Potash Company and its affiliate Jordan Bromine.

As time has passed, the list of potential customers has shortened. Cyprus has discovered offshore gas. Lebanon has serious prospects of finding its own. The political tensions between Israel and Turkey, which would have made an ideal market for Israeli gas, have so far precluded sales there.

There has also been a dream of selling gas through the EastMed, a proposed 1,900km $7bn underwater pipeline running from Israel through Cyprus to Greece and Italy.

But cost and major logistic challenges have crushed that idea, leaving Israel with only one possible customer for a quick sale: Egypt.

Does Egypt need Israeli gas?

Egypt’s need for Israeli gas, however, is questionable. In July 2015, Italian energy company Eni discovered the Zohr "superfield" – the largest gas field ever found in the Mediterranean - then began producing gas last December. Egypt is now expected to have a gas surplus as early as next year.

So when the Delek/Noble-Dolphinus deal was announced this February, many were left shaking their heads. Why did Egypt need this gas? Even if it is going to be re-exported, did it make economic sense?

“The LNG option is also complicated because the extra fees will impair its competitiveness. What happens if Egypt finds lots more gas?”

Further doubts over the deal were cast when reports came out a couple of weeks ago that Eni had made another massive find off the coast of Sinai. Israeli energy stocks plunged as it looked like Egypt might not need Israeli gas at all.

Eni has since denied the reports, saying only that exploration of the Noor field, where the discovery had allegedly been made, will begin in August. But it is only a matter of time say analysts before Egypt discovers more gas - and that’s why this deal is moving forward quickly.

'They may be able to sell some gas to Egypt, but it's not clear for how long'

- David Butter, Chatham House

“At any moment, it could collapse. The idea is just to rush it, to lock it in and to create facts on the ground,” said Rettig. “You put the pipeline, you put the gas in the pipeline, but the gas is already flowing. You are going to stop it now? That’s the idea. Just push through it and make it happen.”

While the deal is currently set for 10 years, analysts said they suspect that it may not last that long, but critically would allow Delek and Noble to continue investing in Leviathan for other deals.

“They may be able to sell some gas to Egypt, but it's not clear for how long,” said Butter.

Shareholders wait for money pipeline

But earlier this month, as Delek shareholders voted overwhelmingly to invest $200m into EMG, the company which carried the cheap Egyptian gas to Israel a decade ago and still controls the pipeline running between Israel and Egypt, the deal continued to move forward.

By investing into EMG, Delek and Noble would hold the largest voting bloc in the company, allowing them to pass a motion to reverse the pipeline's direction.

However, hurdles remain. There are still billions of dollars in settlements hanging over the deal after the state-run Egyptian Natural Gas Holding Company (EGAS) terminated its contracts with EMG to export gas to Israel in 2012.

In 2015, the International Chamber of Commerce in Geneva ordered EGAS and Egypt’s General Petroleum Corporation (EGPC) to pay a $1.76bn fine to the Israeli Electric Company and $288m to EMG for halting the gas supplies.

Egyptian Energy Minister Tarek el-Molla reportedly said earlier this year that the deal hinges on the settlements. Egyptian news site Mada Masr has also reported that the Israeli government had agreed in principle to reduce the amount of the fines owed if the Egyptian government would allow its private sector to import Israeli gas.

And that’s the only advantage that Foada said he could see in the agreement. “The only gain Egypt could have – although it’s not written in the deal, but we can predict it – is the waiver it may get for the fine.”

Given the ups and downs of the past few years, the Delek shareholder said he wasn’t ready to relax.

“I’ll celebrate when I see the money.”

Delek and Noble did not reply to requests for comment by the time of publication. MEE called Dolphinus repeatedly on its publicly listed number, but it wasn't answered.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.