Egyptian refugees struggle to navigate Italian system

From a shelter for migrants in Milan, Italy, Egyptian refugee Mohamed Elanwer held up a folder bulging with paperwork.

"This is 4.5 kilos," he told Middle East Eye over a Zoom call. "This is just three years in Italy."

The folder contained detailed records of the years he spent in exile, including paperwork and photographs. Each episode was precisely dated.

Elanwer has needed a forensic memory to navigate the labyrinthine Italian migration system, and things have only got worse since Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni came to power last year on a promise to crack down on migrants.

While grappling with these new challenges, Elanwer has had to sweep aside the years of trauma that brought him to this point.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

In Egypt, before President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi came to power in a 2013 military coup, Elanwer was a prolific journalist and organiser, co-founding one of the youth movements that helped to drive the 2011 revolution.

After the coup, "fear spread to every aspect of life", he said, as media crackdowns made it impossible for Elanwer to continue his journalistic work, which had already marked him as a target of the regime.

The period between 2013 and 2014 was dominated by politically motivated arrests and enforced disappearances.

For Elanwer, a string of arrests, violent detentions and confrontations with police took a physical and emotional toll; he sustained a spinal fracture and lost hearing in one ear. He also suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder.

Risking death

Elanwer and his friend Hassan, who spoke under a pseudonym for safety reasons after having been repeatedly arrested for protesting against Egypt's handover of two Red Sea islands to Saudi Arabia, belong to a generation forced into prison or exile since the 2013 coup. Many have risked death to reach Europe.

Hassan left for Turkey in 2018 on a tourist visa and stayed there for nearly two years. Unable to find work, he ultimately booked a flight back to Cairo with a stopover in Rome. Upon arriving in Rome, he requested asylum at the airport, leading to a 24-hour detention and interrogation.

"[Police] treated me appallingly," he told MEE. "I was detained in a cell in inhuman conditions."

The next day, he was released and sent to a local reception centre for migrants.

'Now, I don't have any friends left in Egypt... most of them are in exile, dead or in prison'

- Hassan, Egyptian refugee in Italy

"I was instantly reminded of Egyptian prison," Hassan said. "The conditions are a lot worse in prison, of course, but this was a form of prison. My first thoughts were, how do I get out of here?"

In Italy, more than 100,000 "irregular migrants" arrived in 2022, up from around 67,000 in 2021 and 34,000 the year before that. This surge includes a significant number of people fleeing poverty and authoritarian rule in Sisi's Egypt: last year, Egyptians accounted for approximately one in five disembarkations in Italy.

According to data from Frontex, the European border agency, Egyptians were the most common nationality detected along the central Mediterranean route into the EU in the first five months of 2022. The spike has been driven by a collapsing economy that has plunged a third of Egypt's population into poverty, while repressive crackdowns have filled jails with thousands of political prisoners.

These conditions have driven some Egyptians to resurrect smuggling routes previously subject to crackdowns. Following a string of shipwrecks in 2016, Egypt's coastline has been heavily policed, with the European Commission reportedly pledging euros 80m ($86m) to the Egyptian government to stop boats from leaving its shores.

Still, many are pursuing dangerous routes out of the country, risking kidnapping and extortion, or crossing the Mediterranean in unseaworthy boats.

Application rejected

In 2015, Elanwer fled Egypt for Malaysia. For two years, he kept a low profile, running a small business and using a Qatari accent to disguise his nationality.

He was able to sustain this until his passport was stolen in 2017, forcing him into direct contact with the Egyptian embassy. Upon arrival, he was interrogated about his reasons for leaving Egypt, and told that he would receive his passport within a month, he said. It never arrived.

A year passed. Then, in February 2018, Elanwer learned that his passport application had been rejected. A week later, he said, an Egyptian official who introduced himself as an "ex-lieutenant" visited him at his hostel at midnight.

"I had never seen this man before," Elanwer told MEE. "He said to me, 'My son, why don't you go back to Egypt?'" The man also instructed him to post an apology to Sisi on his Facebook page, saying he would receive his passport within a week, Elanwer said.

Terrified, Elanwer fled Kuala Lumpur for the town of Kuala Besut, but said he was hounded by WhatsApp messages, calls and Facebook posts from the same man. Several months later, Elanwer returned to Kuala Lumpur to follow up on his application for UN refugee status, which had been outstanding for three years.

He was given an appointment with an Egyptian supervisor, he said, who requested information about the signatories on his supporting documents; all were Egyptian dissident journalists and activists. His asylum application was rejected shortly thereafter.

'I lost everything'

In response, in June 2019, Elanwer went on a partial hunger strike to protest against the decision and demand an investigation. Twenty-three days later, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) granted him refugee status.

MEE reached out to UNHCR for comment, but did not receive a response by the time of publication.

Amid concerns that his public protest might have attracted the attention of Egyptian authorities, Elanwer soon decided to leave Malaysia. In August 2019, he booked a return flight to Cairo using a temporary travel document provided by the embassy. But, like Hassan, he had no intention of reaching Cairo; at a stopover in Rome, he requested asylum.

"I lost everything in Malaysia... and then I had to deal with the Italian bureaucracy," he said.

The Italian migration reception system involves a network of NGOs and municipalities. Reception centres for asylum seekers are often in isolated areas and offer only the most basic services.

Queues of desperate people trying to apply for asylum outside police stations, along with the recent death of a young Egyptian man who froze on the streets of Bolzano, present solemn reminders of the fatal implications of such policies.

Both Hassan and Elanwer, despite having extensive documentation, struggled to navigate this system, a situation complicated further by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Locked down

Hassan arrived in Rome in late 2019, just ahead of the first coronavirus lockdown, which delayed processing of his asylum application.

He was confined to a crowded reception centre on the city's outskirts for six months, where he shared a room and adjoining bathroom with six people.

Due to budget cuts, just one employee was responsible for hundreds of residents at a time, and Hassan recalled waiting in a long queue to ask a staff member a question.

Frozen meals were reheated in their plastic packaging. Asylum seekers were issued SIM cards, but no pocket money, so they could not buy or cook their own food.

Without the necessary papers, they could not open bank accounts to receive money from family, Hassan said.

"For six months, I was completely isolated... [and] fixated on the idea of escaping," he said.

Although the lockdowns exacerbated the situation, many Italian reception centres do not allow residents to leave for more than one day at a time, with overnight outings prohibited unless required for work. In that case, proof must be provided, something many employers are reluctant to do, because of the attendant legal responsibilities.

Plunged into depression, Hassan kept himself busy with several Italian language courses, which he attended back-to-back, only returning to the centre each day to sleep. In May 2020, he was ultimately granted asylum and moved into a room he found through friends in Rome.

"It was the first time I felt safe," he said. "I slept for 24 hours."

Painful journey

While Hassan relied on a local network of Egyptian activists to help him navigate the murky waters of the asylum system, Elanwer did not have the same connections.

His year-long wait for refugee status in Rome, followed by a nine-month wait for an appointment to receive a temporary residence permit, took a significant physical and psychological toll, he said.

When he was ultimately granted a permit in June 2021, the lack of job opportunities presented a fresh challenge. For a few months he washed cars to make money; he then travelled to Germany for short-term construction work.

When his German visa ran out, Elanwer returned to Italy in September 2022 and lived in a tent on the outskirts of Florence for more than a month.

"The only thing I owned at that time was my tent and 100 euros," he said.

The Italian migration system had Elanwer in a bind, as he needed a fixed address for five years in order to qualify for a long-term residence permit. Any time spent living on the streets would reset that clock.

After another brief stint in Germany, Elanwer volunteered to work at the migrant's shelter in Milan earlier this year.

He receives just 100 euros a month in payment, but, for the first time in several years, he can rely on a roof over his head.

He is safe, but the scars of his journey run deep. He sleeps with his passport and documents under his pillow.

He still has not seen a doctor for his ear and spinal injuries, but it is the invisible wounds - the traumas of the revolution, the suffocating fear he felt in Malaysia, and his separation from his daughter - that will stay with him the longest.

State of emergency

Hassan and Elanwer arrived in Italy before Meloni came to power, and even then, they struggled to navigate an asylum system starved of funding - one that allowed migrants to slip through society's cracks.

Meloni was elected on the back of a promise to stem the flow of migrants reaching Italy's shores. This past April, the Italian cabinet declared a state of emergency, set to last for at least six months, after a "sharp rise" in migrant arrivals. This came on the heels of new regulations that made it more difficult for aid organisations to do their work, sending search-and-rescue ships to distant northern ports before migrants can disembark.

"The majority coming to Italy's southern shores are economic migrants," Italian diplomat Ferdinando Nelli Feroci told told Al Jazeera. "So there is a problem of trying to manage the reception of these migrants, which the emergency scheme seeks to address."

MEE reached out to Italy's interior ministry for comment, but did not receive a response by the time of publication.

Last November, 35 asylum seekers were stranded off the coast of Sicily after the government deemed them ineligible to enter the country.

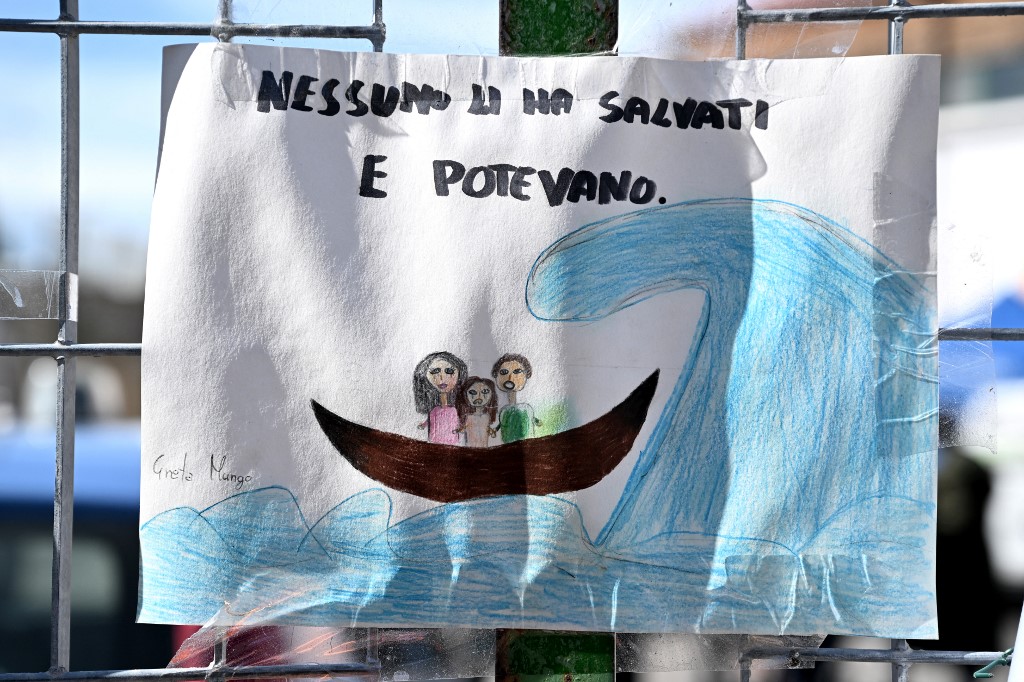

In February, a shipwreck off the coast of Calabria killed more than 90 people. The new restrictions on search-and-rescue operations could contribute to similar catastrophes.

Meloni once said that Italy should "repatriate migrants back to their countries and then sink the boats that rescued them". Today, her government is creating an atmosphere of hostility for people arriving on Italy's shores, one that is hardening into formal structures designed to keep people like Elanwer and Hassan out.

Despite the new network of activists he has come to know, Hassan feels isolated in Italy.

"I lived 23 years in Egypt. I left my family and friends behind," he said. "Now, I don't have any friends left in Egypt... most of them are in exile, dead or in prison."

Reflecting on the last few years, Elanwer is still incredulous at the hurdles he has overcome to reach this point.

"I don't know what the issue is," he concluded wearily. "Maybe the issue is me."

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.