Egypt TV workers demand pay justice as state media star dims

Egypt's state television workers are protesting over the failure of employers to pay their bonuses over several years, bringing into focus the financial problems facing state media in the country.

Tens of thousands of workers, including technicians, administrative workers, presenters, writers, editors, reporters, cameramen and directors, work for the Radio and Television Union, the state-run broadcaster in Egypt.

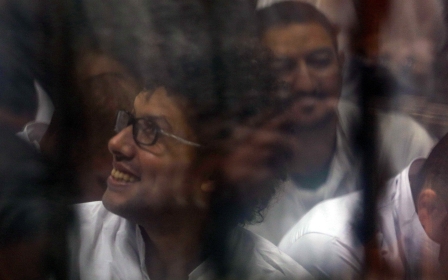

Some of these workers have been protesting for weeks inside the Nile-side union building in downtown Cairo against the failure of the administration of the union to pay them their overdue payments.

'The union borrowed billions of pounds in the past to establish some media projects, but these debts were never repaid'

- Khaled al-Sobki, former head of the economic sector of the union

The union, they say, has failed to pay them their overdue bonuses since 2018 as the country faces rising inflation and a cost of living squeeze.

The workers have raised a long list of demands, including the payment of overdue bonuses and the sacking of union officials for allegedly abusing their power and their involvement in financial infringements.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

"These financial problems are having a heavy toll on all workers," veteran presenter Hala Fahmy told Middle East Eye. "We have enormous financial and administrative corruption."

Egypt's Radio and Television Union is by far the oldest broadcaster in the Arab region.

The union was created in the 1960s by the post-monarchy Nasserite government in its bid to control the media and consequently the public.

The governments that took over in Egypt after that were keen to use the media to dominate the narrative in Egypt and the information given to members of the public.

In 2005, however, the late president Hosni Mubarak loosened the state's grip on the media, which gave rise to a large number of private newspapers and television channels.

In subsequent years, the private media succeeded in outperforming the state media, by demonstrating more openness and courage in discussing social, economic and political problems.

This caused viewers and readers to abandon the state media and turn to the private channels and newspapers in increasing numbers.

The shift in viewership and readership to the private media was followed by an exodus of advertisers to the same media, leaving the state media high and dry.

Billions in losses

The demonstrations by workers at the Radio and Television Union come at a time the state television is running at a loss.

Over 35,000 people work for the union, which has become a symbol of Egypt's bloated civil service sector.

The revenues of the television and radio stations operated by the union amount to a fraction of the cost of operating them, including the salaries of their workers.

The union incurred losses up to 7.066 billion Egyptian pounds (around $455.8m) in the fiscal year 2018/2019, according to a report by the National Media Authority, the state-controlled body that supervises the work of the union.

These losses, it said, are 4.7 percent higher than the losses incurred by the union in the previous fiscal year.

The union's losses in 2018/2019 raised its overall losses to 48.3 billion pounds (roughly $3.1 billion), the authority said.

The union also owes tens of billions of pounds to suppliers and local banks.

"The union borrowed billions of pounds in the past to establish some media projects, but these debts were never repaid, causing interest payments to keep piling up," Khaled al-Sobki, the former head of the economic sector of the union, told MEE.

"The union also lost advertising agencies to private television channels."

Media crisis

But the financial problems facing the state television and the anger of its workers are just a small detail in the larger picture of the crisis of state media in Egypt.

Apart from the aforementioned television channels and radio stations, the Egyptian government runs a large number of newspapers and press institutions that have also been running at a loss for a long time now.

The state-run newspapers, which include some of the oldest in the Arab region, have been suffering a decline in revenues because of their shrinking readership.

There are five major state-run press institutions in Egypt, which produce dozens of daily newspapers, weekly magazines and monthly publications.

'The lack of freedoms and the failure of the newspapers to give their readers real value for their money also stand behind this drop in paid circulation'

- Khaled al-Balshy, former member of Egypt's Press Syndicate

However, there is a marked drop in the sales of these newspapers. The drop in print sales also includes the private newspapers and the newspapers published by some of Egypt's political parties.

In 2018, the nation's 70 daily newspapers sold 1.4 million copies every day, according to the official statistics body, Central Agency for Public Mobilisation and Statistics.

This is a fraction of the daily sales of the nation's newspapers years ago, as Egypt joins the global audience transition from print media to new media channels.

This paid circulation figure is also viewed as very low in a country where the population is over 102 million.

Specialists blame this decline in newspaper sales on fierce competition from the internet, private television channels and foreign media.

"The lack of freedoms and the failure of the newspapers to give their readers real value for their money also stand behind this drop in paid circulation," Khaled al-Balshy, a former member of Egypt's Press Syndicate, told MEE.

The decline in paid circulation also affects the newspapers' ability to attract advertisers, something that translates into financial problems for these newspapers.

One of the nation's largest state-run press establishments was incapable of paying the salaries of its workers in February, sparking demonstrations by the workers similar to those taking place at the Radio and Television Union building in downtown Cairo now.

Lack of freedom

Few media experts are ready to talk publicly about the actual reasons for the loss of viewership by state television and readership by state-run newspapers.

Nonetheless, this decline has its roots in their editorial policies, some people argue.

Egypt's media scene is witnessing a massive regression as far as the freedoms given media outlets are concerned.

The newspapers and the television channels run by the state are preoccupied with defending government policies, probably the last thing viewers want to see and readers want to read.

"To say the truth, I have stopped watching the official television and buying the newspapers a long time ago," Sameh Youssef, a civil servant in his mid-40s, told MEE.

"All the newspapers are a carbon copy of each other, while none of them tries to present anything different to the readers."

Egyptian media, in general, appears also to be losing the race for local readers and viewers to foreign media, amid what amounts to a credibility crisis.

Lack of official interest

"In tightening their grip on the media, state authorities seem to be learning a lesson from the buildup to the 2011 uprising against Mubarak, but in a wrong manner," an Egyptian political analyst, who requested anonymity, told MEE.

"The current authorities in Egypt believe the freedoms given the media as of 2005 had emboldened it into discussing all problems, consequently giving courage to the public to demonstrate against Mubarak and bring him down," he added.

Mubarak had to step down on 11 February 2011, following 18 days of pro-democracy protests against his 30-year rule.

This reinforcement of state control over the media also comes as the government seems to be losing interest in state media, in general, probably because of its declining influence.

'I will keep protesting until I get my rights... I have taken the first step and I will not stop'

- Hala Fahmy, journalist at state TV

Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi complained several times in recent years against the failure of his country's media to discuss Egypt's real problems and the real challenges facing it.

Sisi's administration has been trying to create its own media machine by controlling a large number of private television channels from behind the scenes.

A company reportedly owned by the Egyptian Intelligence Service now owns a huge network of television channels and radio stations that act in unison and offer strong media backing to the Egyptian president and his government.

Since army general Sisi led a military coup against his civilian predecessor Mohamed Morsi in 2013, his government has led what Reporters Without Borders described as a process of "Sisification" in the media.

Over the past nine years of Sisi's rule, the government has overseen a campaign against free speech, eventually bringing the entire media landscape under his control. The country has become one of the worst jailers of journalists, and currently ranks 166 out of 180 on the RSF's press freedom index.

'I will keep protesting'

Fahmi, the television presenter, was suspended for three months on 17 February for inciting her colleagues to demonstrate to demand their financial rights.

Some of her colleagues who were caught in the act of demonstrating faced the same fate.

This is why some of the workers are afraid to participate in the protests, even as their demands are far from fulfilled.

Fahmi says she will keep protesting until the administration of the union and the National Media Authority give her and her colleagues their financial dues.

"I will keep protesting until I get my rights," Fahmy said. "I have taken the first step and I will not stop."

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.