EU countries approve arms sales to Saudi, UAE worth 55 times aid to Yemen

European governments and the European Union publicly wring their hands about the "human tragedy" and need for "life-saving assistance" in war-torn Yemen.

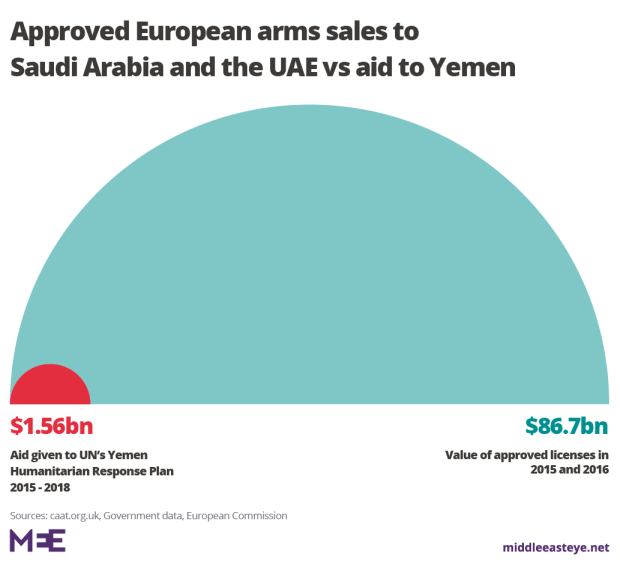

Yet while the Saudi-led coalition has bombed the region’s poorest country over the past three years, the EU and European countries approved the sale of more than $86.7bn in arms to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, according to figures compiled by Middle East Eye.

The reality is the provision of arms extends conflicts and leads to humanitarian disasters, so to an extent the arms trade fuels the need for aid assistance

- Jeff Abramson, Arms Control Association

The value of the licences which the countries issued in 2015 and 2016 - the only years for which data is available - amount to more than 55 times what the EU and European countries have donated to the UN’s chronically underfunded Yemen Humanitarian Response Plan.

Meanwhile, independent researchers estimate that more than 56,000 Yemenis have been killed with the UN warning “a clear and present danger” of an imminent famine engulfing 14 million Yemenis – or half of the population.

Many governments have promised during the course of the war to stop or restrict sales of the weapons that are being used to maim Yemenis, and the killing of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi last month brought a new wave of public pressure to halt deals with the Saudi kingdom.

But only Germany and Norway have suspended their sales – until Khashoggi’s murder is explained - while the UK, France and Spain have all signalled that they will continue business as usual.

Experts say the continuation of the sales, which politicians often justify by pointing to job creation, security cooperation and trade relations, reveals a fundamental disconnect for Western governments between their actions and Yemen’s humanitarian crisis.

“The UK and many of its EU allies insist there is no military solution to the conflict, yet they themselves are supplying the weapons that are fuelling and prolonging the hostilities,” says Ben Donaldson, head of campaigns at the United Nations Association-UK, a grassroots policy group.“There has just been one UN Security Council resolution in three years of conflict, which is very surprising given its severity compared to other conflicts, and the UK is taking sides in the conflict, which flies against its position of ‘penholder’ and its responsibility. The UK’s position is to support Saudi Arabia.”

Jeff Abramson, a non-resident senior fellow with the Washington, DC-based Arms Control Association told MEE: “The reality is the provision of arms extends conflicts and leads to humanitarian disasters, so to an extent the arms trade fuels the need for aid assistance. It’s a perverse cycle.”

Stockpiling for decades

For decades, billions of dollars in arms sales flowed into the Gulf to be stockpiled and largely forgotten, while the revenues have piled up into European bank accounts.

Ministers did not have to do mental gymnastics to justify such deals, saying the sales were for "defensive purposes". Or as the French defence minister put it in February, they were “not supposed to be used”.

Jobs were created at home, and the deals kept the doors open to closer economic and political ties with oil-rich Gulf kingdoms.

The only potential crack in the narrative was if news surfaced of the greasing of palms to secure the deals. Take the Al-Yamamah oil-for-arms deal agreed by Saudi Arabia and Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s which netted British arms giant BAE around $55bn in revenues.

An eventual investigation into the deal was shut down in 2006 by then prime minister Tony Blair after pressure from the Saudis.

Otherwise, arms exports were an easy sell to the public. Shady deals there might be, but no one was getting killed, and nobody needed any humanitarian assistance, even if a blind eye was turned to domestic oppression and proxy wars.

But with the war in Yemen, that position no longer holds.

Since the war started in March 2015, more than 10,000 Yemenis have been killed – at least, that’s the figure that’s been reported, without change, over the past two years.

In a report released in October, Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project, an independent conflict research group, has estimated that 56,000 have been killed since January 2016 which does not include those who have died from hunger and disease – and is likely, said the researchers, to be an underestimate.

The growing number of civilians killed and maimed by coalition forces – at weddings, in marketplaces and on school buses - has led to increased pressure on governments to justify their arms sales to the kingdom and the UAE.

In 2015 and 2016, the only years for which EU arms export reports are currently available, nearly every EU country has sold arms to Saudi Arabia and the UAE. MEE has found:

- In 2015, 21 EU countries approved licences for the export of arms, ranging from bullets to bombs to jet fighters and specialised military components, worth $25.3bn to Saudi Arabia and $11.4bn to the UAE, totalling $36.7bn. Of this total, $14.4bn was for aircraft, bombs and grenades, the primary causes of civilian deaths.

- In 2016, 17 EU countries licensed the sale of even more weapons worth $18.3bn to Saudi Arabia and $31.7bn to the UAE, totalling $50bn.

- While EU-wide figures are not available for 2017, those provided by individual countries indicate that arms sales have largely continued at the same rate. In 2017, the UK and Germany licensed $2.3bn in arms to Saudi Arabia and the UAE, according to figures provided by governments and the Campaign Against the Arms Trade.

As the sales have continued, the UN’s Yemen Humanitarian Response Plan campaigns have remain underfunded:

- Overall since 2015, the EU and some European countries have given $1.56bn to the UN’s response plan, according to UN OCHA figures. That's equivalent to 1.8 percent of approved European arms sales to Saudi Arabia and the UAE in 2015 and 2016.

- The European Commission, towards which all EU states contribute, has provided $507.2m to Yemen, roughly half to the UN’s response plan, for the past three years. That’s equivalent to 0.58 percent of $86.7bn in approved European arms sales in 2015 and 2016.

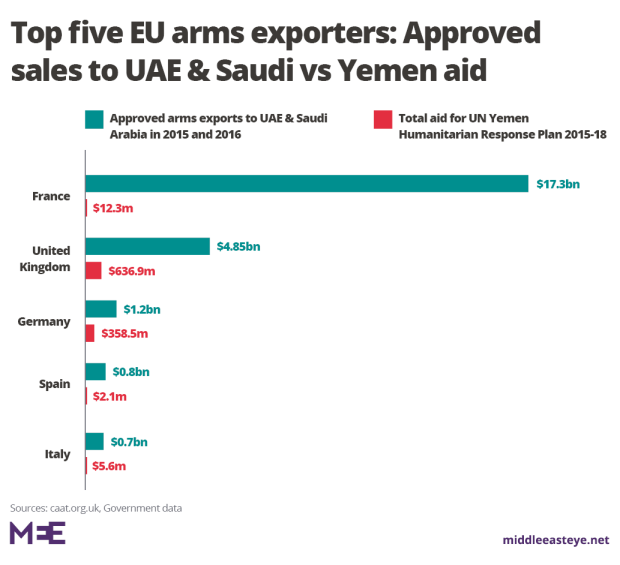

- During the same period, the UK has provided $733.4m in humanitarian aid for Yemen, according to government figures provided to MEE. Of that, $636.9 million went to the UN response plan, equivalent to 13.1 percent of the UK's $4.85bn in approved licences for 2015 and 2016.

- France is the lowest overall donor compared to approved licenses, providing $12.3m in aid from 2015 to 2018, just 0.07 percent of $17.3bn in approved arms sales in 2015 and 2016. However, experts say France's licensing figures may be inflated because the country includes ongoing negotiations in their totals.

- The fourth and fifth largest European arms suppliers, Spain and Italy, are tight-fisted when it comes to humanitarian aid, giving equivalent to 0.26 percent and 0.76 percent of their approved arms sales in 2015 and 2016 respectively.

- Germany has been relatively generous with aid of $358m from 2015-2018, equivalent to 29 percent of $1.2bn in licenses approved in 2015 and 2016. Sweden, which had $1.33bn in sales in 2015 and 2016, has given $105m in aid for 2015 to 2018, or 7.93 percent of the value of approved licences.

- Only Ireland has exceeded humanitarian aid contributions compared to approved arms sales, at 123 percent in 2015 (there were no exports in 2016).

As the conflict continues in Yemen, the UN’s 2018 humanitarian response plan is currently 35 percent underfunded. The $1.04bn shortfall is just 1.1 percent of approved European arms sales to Saudi Arabia and the UAE in 2015 and 2016 alone.

'Maximising arms sales or human rights, it’s always arms sales that wins'

- Andrew Smith, Campaign Against the Arms Trade

While approved licenses are clearly different from actual exports, in Europe, they nearly always become actual sales, says Andrew Smith, spokesman for the Campaign Against the Arms Trade (CAAT).

"If a licence is signed which isn't hugely skewed by change in legislation, you have given permission for the sale to go ahead. That means the government won't block it and, if they do block or suspend it for some reason, that gets calculated later on anyway," Smith says. The one exception is France which has included licences still under negotiation since 2014.

Overall, given the choice between “maximising arms sales or human rights, it’s always arms sales that wins,” he says.

And the aid, says Andrew Feinstein, executive director of Corruption Watch, and author of The Shadow World: Inside the Global Arms Trade, is “part of a PR veneer created around justifying the arms industry”.

Hollow words

As the world’s largest humanitarian disaster has unfolded, there has been pressure from activists and civil society groups over the past three years which has led Spain, the Netherlands, Belgium and Sweden to announce that they were freezing or restricting of arms exports to the Gulf.

The EU also made overtures at restricting arms exports, with the Council of Ministers – the executive government of the EU - passing a non-binding motion in December 2016 to ban all arms sales to Saudi Arabia.

However, despite “a majority voting for the motion, the request was put aside and it has not happened,” said Pieter Wezeman, senior researcher, arms and military expenditure programme at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI).

“There’s often a gulf between what is said and done in practice,” says Smith from CAAT.

Furthermore, the EU’s attempt at an embargo on arms sales to Saudi Arabia did not include embargoes on other coalition members, including the UAE and Egypt. France, for instance, sold naval vessels to Egypt that could have been used to enforce the maritime blockade of Yemen, notes Wezeman.

“The Dutch were supportive of the call for an embargo and not providing material for the aerial campaign, but they were still selling naval equipment; those components could be used in the blockade. They try to look progressive but it’s still business as usual,” says Anna Stavrianakis, senior lecturer in International Relations at the University of Sussex and author of Taking Aim at the Arms Trade.

No meaningful regulation

So why do the sales continue? Jobs and political influence on the countries that arms are sold to are often used to justify the continued policy.

But one primary reason for the EU’s inability to rein in arms exports to the Gulf is an unwillingness to regulate the military industrial complex due to its powerful influence over governments and pervasive corruption in the sector, say observers.

Feinstein of Corruption Watch says there is, in fact, no meaningful regulation of the arms industry in Europe.

“The UK and Germany point out national legislation and rigorous exporting licences, and being signatories to treaties they champion, but by exporting to Saudi Arabia and the UAE they are violating their own national laws, the EU Common Position on arms exports, and the Arms Trade Treaty,” he says.

“There is nothing that compels them to do anything differently. National parliaments are completely powerless when it comes to the arms industry.”

The industry has a strong lobby through government contracts, interlinkages with the military establishment, and a revolving door of politicians who are rewarded with positions on the boards of arms’ companies once out of office, according to Feinstein.

Another problem, say observers, is corruption inherent within the industry.

The arms trade is unregulated because the largest manufacturers (the USA, UK, Russia, France) all sit on the UN Security Council, so why would they go against their own business?

- Loretta Napoleoni, Italian economist

Lacking the influence of the US, European companies have to frequently sweeten arms deals, which range from investments in buyer countries to gifts of personal jets, to payments to politicians through offshore bank accounts.

“The US is slightly less corrupt as they have enormous political clout, but all European countries are more corrupt than the Americans, they’re far dirtier,” says Feinstein.

None of the five largest West European suppliers - France, Germany, the UK, Spain and Italy, which together accounted for 23 percent of global arms transfers in 2013–17, according to SIPRI figures - appear to have any appetite to better regulate the arms trade, he added.

Loretta Napoleoni, an Italian economist and expert on terrorist financing, told MEE: “The arms trade is unregulated because the largest manufacturers (the USA, UK, Russia, France) all sit on the UN Security Council, so why would they go against their own business?”

Bread and cash

In fact, there are more requirements imposed by financial regulators on NGOs globally, focused on where their donations come from and how their money is spent, than on global arms, she said. “There’s a lot of fuss about charities but almost nothing about arms,” says Napoleoni.

The Paris-based Financial Action Task Force (FATF), an influential global body which develops policies for countries to adopt on anti-money laundering (AML) and countering the financing of terrorism (CFT) standards, has a specific recommendation for NGOs but not for the arms industry.

“The amount of due diligence and compliance that humanitarian and development organisations working in conflict zones have to do is incredible. It is no exaggeration to say it is crippling some organisations from operating,” says Ben Hayes, an independent consultant who advises charities and foundations on AML and CFT rules.

“To the founding members of FATF, which is the EU and the USA, corruption is viewed as something that happens exclusively in developing countries.”

The restrictions on NGOs operating in Yemen has had a significant impact on the ground, says Sherine El Tarboulsi-McCarthy, a research fellow with the Humanitarian Policy Group at the Overseas Development Institute (ODI).

“International humanitarian organisations face a lot of challenges to send and receive funds for Yemen. Getting bread and getting cash are the two main challenges for Yemenis,” she says.

And critically, there is also the historical picture to consider: jets sold to Saudi Arabia under the Yamamah deal and British-made cluster bombs exported before the UK passed legislation banning the weapons in 2010 are in use in Yemen today.

“Almost 30 years later, the cluster bombs were still operational, and used in air strikes,” says Smith of the Campaign Against the Arms Trade. “Weapons sold today could be used for atrocities for years and years to come.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.