Families of Tunisia’s militant fighters speak out about radicalisation

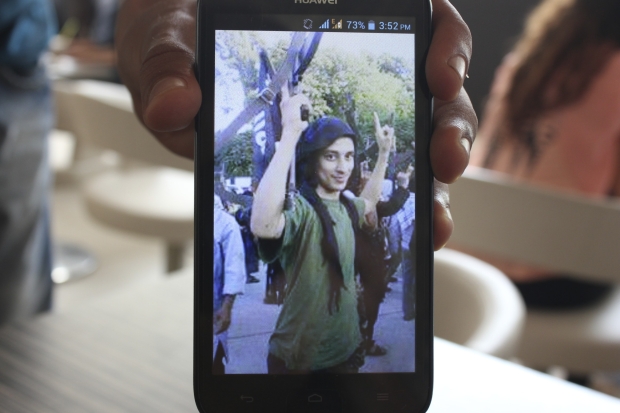

TUNIS – In the picture, Amr Jendoubi’s face is lean and youthful. He has a light, wispy beard, barely visible in the pixelated cell phone image. Both of his arms are raised. His left index finger is pointing to the sky, and in his right hand he is holding an AK-47.

Behind his head, someone in the crowd where he is standing is carrying the black flag of the Islamic State (IS). His one finger salute is not a random gesture, but a common hand signal used by IS fighters to signify their belief in the oneness of god and their rejection of what they consider to be heretical interpretations of Islam.

In the background of the image, the sun is shining and the trees are green with foliage. Jendoubi is seen smiling broadly, but the picture would be one of the last ever taken of the 20-year-old who was killed in US-led coalition airstrike on 5 Feb 2015.

On a recent muggy afternoon in Tunis, Omar Jendoubi, Amr’s twin brother, sat inside an air-conditioned burger joint and café around the corner from the Tunisian parliament.

He talked about how he was working on his baccalaureate studies, the step before university in Tunisia’s French-adopted education system, but freely admitted he doesn’t take his studies too seriously.

Omar’s hair is closely cropped on the sides and the top is neatly arranged with gel in a style inspired by European football stars. He dons a V-neck t-shirt and blue jean shorts. The burger joint/café is full of young men wearing similar attire and girls with pressed hair and neatly done makeup.

“Before he used to talk on the Internet with girls. He was a normal person,” Omar said of his twin brother. Following Tunisia’s revolution in 2011, however, Amr was caught up in a wave of religiosity that swept the country after years of religious repression under the leadership of ousted president Zine El Abdine Ben Ali.

Along with a group of friends in the neighbourhood, Amr started praying and going to the mosque regularly. Soon enough he stopped his other activities, Omar explained.

At that time, the mosque in their neighbourhood was not under the control of the Ministry of Religious Affairs, which, according to Tunisian law, is responsible for appointing imams.

“The mosque wasn’t under [their] control for four years,” Omar said. “The imam was always encouraging people to go to Syria.”

Amr took these views home with him and tried to convince Omar to adopt his beliefs and lifestyle. “He talked to me about the Koran and tried to convince me to think like him,” Omar said, adding that he wasn’t able to counter his brother’s arguments because he didn’t know enough about religion.

Omar went to the mosque with his brother a couple of times, but it didn’t appeal to him in the same way it appealed to Amr, who he described as quieter and less outgoing.

“I’m much more fond of football than anything else,” Omar said, while trying to explain why the religious lifestyle didn’t appeal to him.

According to Omar the pair had initially started drifting apart after middle school, and were not that close by the time Amr became more religious but the family nonetheless got an inkling that Amr was planning to travel to Syria.

In January 2014, Amr left for Syria with a group of other youth from his neighbourhood. While the family had informed the police who tried to confiscate his passport, Amr lied and said he lost it. He then snuck away and illegally crossed into Libya where IS contacts gave him a stamp as if he had legally crossed the border.

After Amr left, both of his parents became sick from shock and depression, according to Omar. “I lost 25 kilos,” he added.

The fact that Amr was killed in Syria has taken a long time to sink in. “It’s kind of a gradual shock,” Amr said. “He was already absent.”

From Libya, Omar said that Amr he went to Turkey and then crossed into Syria. “He went for religious reasons,” Omar said. “Economically we are fine.”

Amr is one of an estimated 3,000 young Tunisians who left the country following its 2011 revolution to fight in Syria and Iraq. The trend has left observes perplexed as to why youth in what is frequently referred to as ‘the Arab Spring’s only success story’ have flocked to foreign battlefields to fight in the ranks of IS.

The phenomenon was brought centre stage in March when two Tunisian gunmen, believed to have trained with Islamic State in Libya, returned home and carried out a brutal attack on the country’s Bardo National Museum. Twenty-two people, largely European tourists, were killed and some 50 others injured in the ensuing massacre.

Many commentators have blamed Tunisia’s struggling economy, high levels of youth unemployment, frustration with the slow pace of change and continued abuses, particularly by the police, as the root causes of radicalisation. But others in Tunisia believe these are only contributing factors, with various other factors also at play. According to Ghazi Mrabet, a lawyer who has had a friend and one of his clients leave to fight in IS, these mainstream explanations do not help us to understand why some people chose to join IS while others don’t. “A lot of young people are subject to the same treatment and never thought about leaving to Syria,” Mrabet said.

Instead, Mrabet believes that the people who choose to go to Syria are believers in IS’s ideology and want to live in a place where they believe Sharia, or Islamic law, is being applied literally.

“People who want to improve their economic situation go to Italy. People who want to improve their spiritual situation go to Syria,” said Mohamed Ikbel Ben Rejeb, founder of the Rescue Association of Tunisians Trapped Abroad (RATTA), an organization that advocates on behalf of the families of Tunisians who have gone to fight in Syria and Iraq.

Marwen Douiri’s story helps to show the unique journey that young Tunisians go through on their way to joining groups like IS.

In a music video dating from December 2011, Douiri, better known by his rap name Emino, is seen in a club surrounded by women in short, tight dresses holding lip-stick stained glasses, presumably of alcohol.

By 1 April 2015, however, Douiri Facebook page told a completely different tale. Pictures on his wall showed him standing in a pastry shop in Syria with three bearded men. In the images, Douri is wearing a khaki green shirt that reaches to his knees, and his pants, also khaki green, are bunched up above his ankles in a style of dress common among Salafi Muslims. He is holding up his right index finger in the IS salute. Another picture from 24 April shows him dressed in all black sitting on a park bench next to an AK-47.

Between 2011 and 2014, Douiri, who grew up in a middle class family, had a number of discouraging run-ins with the Tunisian authorities before joining IS in March of this year, according to Mrabet, his lawyer Mrabet.

Douiri’s legal problems began in 2012 when he was arrested and sentenced to one year in prison for smoking marijuana. He was released at the end of 2012 after serving a month and a half of his term, but several months later found himself arrested again for collaborating on rapper Weld El 15’s song ‘The Police are Dogs.’

This time, Douiri was sentenced to six months probation after appealing an initial sentence of two years prison time. Weld El 15 received a two year prison term, of which he served only part, according to Mrabet.

During his own trial and the trials of his friends, Douiri grew discouraged with the state of affairs in Tunisia. After Weld El 15 was sentenced in 2013, Mrabet remembers Douriri leaving the courtroom and saying: “I’m so fed with this country… This is a country that doesn’t let you dream. This is a country that kills your ambition.”

Even after his time in jail and his statements of frustration, there was no change in Douiri’s behaviour that suggested he was embracing IS-style ideology, according to Mrabet.

Instead, the change happened quickly at the end of 2014 with no apparent trigger. Douiri started to drop out of the rap scene. He also refused to show up to court for his legal appeals and gave up smoking marijuana and drinking.

Mrabet says that he cannot find a reason for Douiri’s decision to join IS. Douiri wrote on Facebook that he didn’t join the group because of the police harassment, but because he agreed with the group’s ideology, according to Mrabet.

While harassment by authorities was not the leading factory for Douiri leaving, Ahmed, a 25-year-old medical student who asked that his name be changed to protect his identity, says that it was the primary reason why his brother Brahim, also an alias, went to Syria.

Brahim became a practicing Salafi in 2007. Under the Ben Ali government, people who wore beards and prayed the morning prayer at the mosque were subject to police harassment. Brahim was arrested and imprisoned. During his time in jail he was also tortured, according to Ahmed.

After he was released from prison, Brahim’s beliefs became more violent. “He was a jihadist. He believed that jihad is a big part of the religion,” Ahmed told Middle East Eye.

Brahim, whose family is also middle class and educated, saw the Tunisian revolution as an opportunity to practice and preach his religious beliefs without persecution. He became the imam at the local mosque, the same one that Amr attended after the revolution, and often appeared on television expressing his beliefs. “After the revolution, he was happy,” Ahmed said of his brother.

Following the storming of the US embassy in Tunis by a crowd of predominantly Salafi protesters in 2012, the Tunisian government accused Brahim of inciting the protesters to violence. The charges didn’t stick, but after the case Brahim was subject to weekly harassment by the police, according to Ahmed.

In March 2014, a couple months after Amr and a number of other youth from the neighbourhood left for Syria, the police came to Brahim’s house looking to arrest him again. Brahim was not home. The officers put a gun to Brahim and Ahmed’s little brother’s head and demanded to know where he was, according to Ahmed.

After hearing about the incident, Ahmed recalled that Brahim said that “they want me dead or alive. I have to leave Tunis.”

Brahim then went to Libya with his wife, who he had been married to for less than a year, and made his way to Syria two months later where he now lives in the IS stronghold of Raqqa.

“He wanted to stay in Tunisia, but he didn’t have the freedom to do all the things he wanted to do,” Ahmed said. “The biggest thing that forced him to leave was the harassment of the police.”

“We ask him to come back, but deep inside we know if he comes back to Tunisia he will pass a long period in jail,” Ahmed continued, saying he didnt expect to see his brother again.

“Me, I chose to be a doctor. Brahim, he chose to be a Jihadist in the Islamic State,” he added. “I support Brahim because he is my brother, but I don’t support the Islamic State.”

The time that Brahim went to Syria also coincided with the period when the mosque in Omar and Ahmed’s neighbourhood was brought back under the control of the Ministry of Religious Affairs. “Since the Ministry of Religious Affairs took over the mosque [radicalisation] has gradually decreased,” Omar said of the situation in his neighbourhood.

After the revolution, there were more than 1,000 mosques that were not under control of the Ministry of Religious Affairs. By the end of 2014, the ministry had succeeded in bringing almost all of them fully back under control, according to Abdessatar Badr, the Chief of Staff of the Ministry of Religious Affairs.

As a result, the majority of people involved in recruitment have either moved underground or left for Syria, Iraq or Libya. Recruitment now primarily takes place online through social media, such as Facebook and Twitter, according to Ben Rejeb of RATTA.

But the problem is far from over. Instead, the main challenge facing the Tunisian government has also shifted.

“Recruitment is no longer as dangerous as the fact that people are coming back,” Ben Rejeb added.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.