'Fed up': Syrian refugee marks 50 days trapped in Malaysian airport

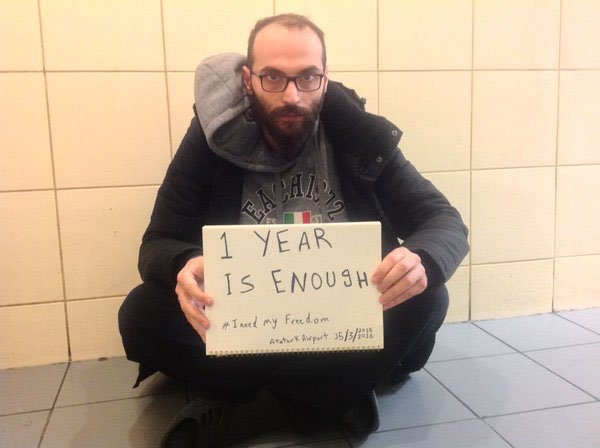

Journalists, rights groups and intermediaries offering a precarious stay in Malaysia have all come and gone, but Syrian asylum seeker Hassan al-Kontar has remained in the same Kuala Lampur airport for 50 days after being left stranded by immigration officials and airlines.

Impatient for a solution before his passport expires in eight months, Kontar has found that even a recent whirlwind of media attention has done little to secure the freedom he desires after years of uncertainty following his refusal to serve in the Syrian military.

The media are only asking me about how I’m sleeping, they’re still asking me what do I eat

- Hassan Kontar, Syrian asylum seeker

Kontar had been living and working in the United Arab Emirates since 2006, but lost his legal status when the war broke out in 2011 because the Syrian embassy refused to renew his passport.

A friend later helped him get a new passport, but he was detained by UAE authorities in 2016 when he tried to get renew his UAE visa after living for years without documentation.

Refugees have no legal status in Malaysia, but in recent weeks, Kontar was unofficially offered a permit under a scheme the country set up for Syrians in 2015. However, the card offers neither security, nor the right to work or travel.

“I’m fed up of running, of being illegal,” the 36-year-old Kontar told Middle East Eye by phone, occasionally becoming audibly frustrated, sighing and speaking almost frantically about his problems. “Half-solutions are not solutions, half a life is not a life.”

He is unable to travel beyond a small section of the airport, sleeps under a stairwell and eats packaged airline meals. He occasionally tries to break the monotony by dipping into his dwindling savings to pay airport workers to bring him coffee or McDonalds meals and with a daily routine of listening to his favourite songs by Lebanese singer Fayrouz.

'Not just Hassan'

An activist in Malaysia who has worked closely with Syrian and Yemeni refugees, but who did not want to be named for fear that they could be targeted under a controversial new “fake news” law, told MEE that the card offered to Syrian refugees was essentially useless because Malaysia was not a signatory of the 1951 refugee convention.

The permit system is run by the Malaysian Humanitarian Aid & Relief organisation, known as Mahar, but the activist said it offers refugees no protection and involves an invasive questioning process that has to be repeated every year.

The activist said he has worked with refugees who were detained for months without any access to visitors and activists had to bribe guards to get medicine to them.

The international community has to take responsibility about not just Hassan, about all asylum seekers

- Activist working with Syrian and Yemeni refugees

The Human Rights Commission of Malaysia reported in 2017 that 118 people had died in Malaysian detention centres in the previous two years, many of them because of untreated health conditions.

Mahar’s interviews involve questions about the applicant’s religion and how they practice it and are followed up with home inspections, the activist said, suggesting they discriminated against minorities or those who did not fit Malaysia’s political or social norms.

“They clearly said they want to bring people who will not disturb the harmony of the Malaysian community,” the activist said. “I’m sorry to mention that but this is the reality, this is how things work.”

Mahar has been contacted for comment.

The process can take months and Kontar, whose visa expires in January 2019, is worried that anything other than a direct solution could leave him further stranded because most visa applications require a passport to be valid for at least six months.

“The international community has to take responsibility about not just Hassan, about all asylum seekers,” the activist said.

Only a symptom

Kontar applied on Thursday to be allowed to be travel to Canada, with local volunteers requesting the immigration minister expedite his case on humanitarian grounds.

Kontar has also felt uncomfortable with the nature of much of the media attention, which came in a short, intense burst and focused, he felt, mostly on the quirks of his individual situation rather than what it showed about the Syrian war.

There have been several cases of Syrians or Palestinian refugees from Syria becoming stranded in the same airport because Malaysia offers limited visa-free stays to most Middle East countries, but it then becomes difficult for them to travel elsewhere.

In 2015, Syrian refugee Fadi Mansour spent more than a year in Istanbul airport after he tried to travel to Germany with false documents.

The nagging fear for Kontar is that he could be deported to Syria, where he left in 2006, and being arrested because of his refusal to fight for President Bashar al-Assad’s army.

He said the thought of returning conjures a nightmarish image of his own house, and a library his late father painstakingly built inside it, burning.

“I cannot bomb my own house, even if it’s not my house. Every Syrian’s house is my house, every Syrian is my brother,” said Kontar. “I know that i’m here only because of my principles, that fighting is not the solution.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.