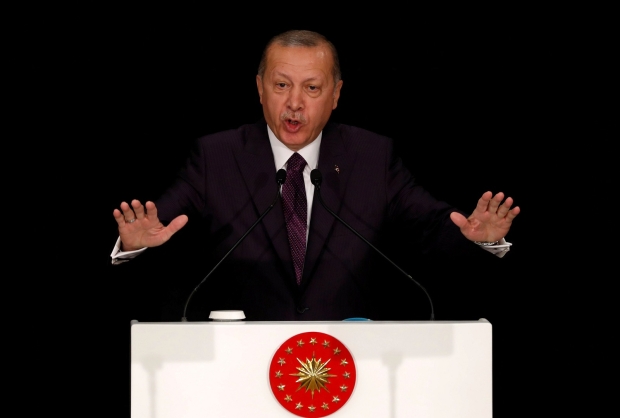

Free 'the doomed': Erdogan's allies want amnesty for Turkish prisoners

ISTANBUL, Turkey - Tens of thousands of prisoners would be freed from Turkey's jails under a proposal before the parliament, despite reluctance from President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's ruling AKP (Justice and Development Party).

The MHP (Nationalist Movement Party) brought forward an amnesty law on Monday which, it says, would relieve pressure on overcrowded jails and release those imprisoned by politically-influenced judges.

But critics say the law would aid ultra-nationalist criminal gangs which have the sympathies of MHP leader Devlet Bahceli.

The seven-point proposal first needs to be discussed by the parliament's Justice Committee before it is voted on by lawmakers; a majority would make it law. The MHP says that the law would result in the release of an estimated 162,000 people.

Proposing the law, Feti Yildiz, the MHP’s deputy chairman, said in a press conference that its aim is “to release the ones who faced unjust treatment by FETO members in the justice system".

FETO is the name used by the Turkish government and its political allies to describe the group behind the failed coup of 15 July 2016. Ankara has designated the movement, led by former Erdogan ally Fethullah Gulen, as a terrorist organisation and dismissed thousands of its supporters, including judges and prosecutors, from public office.

According to Yildiz, there are currently more than a quarter-of-a-million people in Turkish jails, including 194,404 who have been convicted and 59,131 others including 2016 coup suspects awaiting trial, but the capacity is only for 211,274.

Who would be free under the amnesty?

Under the plans, those most likely to be released would have less than five years to serve in their sentences, depending on when the law is passed.

Those excluded would include prisoners convicted of genocide as well as crimes against humanity and the state; those convicted of serious crimes including rape and murder; and those who spoke out against the legacy of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, Turkey's founding father.

Bahceli first raised the idea of an amnesty back in May, one month before the presidential and parliamentary elections in June, during which his party formed an electoral alliance with the AKP.

On 12 May, Bahceli posted a tweet calling for amnesty for the ultra-nationalist gang leader, Alattin Cakici, who is currently serving multiple sentences for murder, money laundering and leading an illegal armed group.

Bahceli described Cakici and Kursad Yilmaz, another crime syndicate chief, as his “brothers who love their nation and country”.

In late May, Bahceli visited Cakici when he was taken from prison to hospital.

Cakici was first arrested after the Turkish coup of 1980 and accused of murdering 41 people allegedly involved in leftist movements. He has fled Turkey at least twice: when he was found in 2004 in Austria, he was carrying a special service passport under the name of a former intelligence chief.

Intelligence reports leaked to Turkish media in the early 2000s showed that Turkey's MIT intelligence service had used Cakici for “clearing terrorists” and carrying out "actions that couldn’t be taken legally”.

What does the president think?

Erdogan was less than enthusiastic for an amnesty while on the campaign trail. But the AKP is now dependent on the MHP for its parliamentary majority: at the election, it saw its number of seats cut to 290 in the 600-seat chamber, while the MHP increased its number to 49.

An AKP source told MEE that while other issues between the parliamentary partners had been resolved, the MHP is still keen to introduce an amnesty despite a lack of public support.

Turkey has had amnesties in the past: during the last one, in 2000, an estimated 45,000 convicts were released, including some who had been jailed for murder, rape and child abuse.

On Sunday, Erdogan told reporters that AKP lawmakers would look at the bill but he remains cautious. “Our basic principle is that if the crime was against the state, the state can forgive that. But if the crime was against the people, it’s not the state but the people who have the authority to forgive that.

"When I look at what they are saying, I see that most of the convicts included in the proposal are the ones who committed crimes against the people. There are not 162,000 people who committed crimes against the state," Erdogan added.

What do other parties think?

The Republican People’s Party (CHP), the main parliamentary opposition with 143 seats, has said it is studying the details of the proposal.

Ozgur Ozel, deputy chairman of the CHP’s parliamentary bloc, told Turkish media on Tuesday that it was vital to know whether those who were released had been rehabilitated and the likelihood of them committing fresh crimes.

"The CHP is not against the amnesty in principal, but it’s not possible for us to say we support it. We have to investigate and work on the bill first because it’s a very sensitive issue."

The amnesty should be enlarged for the crimes of promoting terrorism and freedom of expression. It should exclude ordinary crimes.

- Faruk Gergerlioglu, HDP MP

But the Iyi Party, which numbers 40 MPs, said that while it was not against an amnesty in principle, the proposed law would release drug dealers, which it could not agree with.

Hasan Seymen, deputy chairman, said: “That’s unacceptable for the Iyi Party, that any law regarding the amnesty would protect any individual or a group, or any terrorists."

The pro-Kurdish People’s Democratic Party (HDP), which is the third biggest party in the parliament with 67 seats, has not taken an official line yet. But Omer Faruk Gergerlioglu, one of its MPs, told Turkish media that any amnesty should include political crimes as many trials and verdicts in the Turkish judiciary had come under political influence.

“The amnesty should be enlarged for the crimes of promoting terrorism and freedom of expression. It should exclude ordinary crimes,” he said. In May, Sezai Temelli, co-chair of HDP, accused the MHP of trying to release mafia leaders of organised crime.

Many HDP members and mayors of Kurdish-majority towns and cities are in jail, accused of promoting terrorism and supporting the PKK, which has been fighting the Turkish state for more than 30 years and is considered a terror organisation by the government.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.