Ghannouchi, like Mandela, risks all for reconciliation and democracy

TUNIS - Outside the front door of our hotel in downtown Tunis a ceremony was taking place.

Habib Bourguiba – viewed by some as the founder of the nation, by others as a notorious despot – was restored to his former glory in the form of a bronze statue. Bourguiba on his horse dominates the main drag, an echo of the Champs Elysee.

One of Bourguiba’s final acts as president before he was deposed 30 years ago, was to order the retrial of a prominent member of the opposition. Life imprisonment was not enough for Bourguiba. He wanted to execute the man.

That man on death row was Sheikh Rached Ghannouchi, the spiritual leader of the Arab Spring - and revered by many as the founding father of post-revolutionary Tunisia.

Bourguiba and his horse had been whisked away by Ben Ali, the dictator who followed him and when we later asked Sheikh Ghannouchi’s opinion of the ceremony, this was his reply: “Bourguiba is a great personality. You cannot airbrush him out of our history. He guided a national movement which liberated Tunisia. I cannot negate that. It is a reality. I am not in favour of this statue - but it is not a problem for me.”

Bourguiba and Ben Ali imprisoned, tortured and forced into exile tens of thousands of Islamists.

Nor is it a problem for his party, Ennahda, to be supporting the minority parliamentary faction of Nidaa Tounes, whose raison d’etre is to oust Islamists and restore secular governance. Not a problem, either, to form a government with them and not a problem to support the current president, Beji Caid Essebsi, who was a minister in Bourguiba’s government.

The Emiratis, sources within Nidaa Tounes told Middle East Eye, offered to give Tunisia between $5bn-$10bn if Essebsi ditched his power-sharing agreement with Ennahda. He refused.

Ghannouchi said of him: “I have enough confidence in our president. I have confidence in his patriotism and he is elected by the Tunisian people. His authority does not depend on the support of a foreign power.”

Ghannouchi’s emphasis on reconciliation comes straight out of Nelson Mandela’s playbook in South Africa. But the Tunisian leader grounds his calculations in hard politics, too, which is why he believes he can keep Essebsi on the straight and narrow.

“He knows a large section of the Tunisian people elected Ennahda and he needs Ennahda to consolidate his government. We need his party to make a balance, to make a solid base for our state and our government. Power is based on the balance of power. The balance of power in Tunisia needs collaboration between the president, his party and our party. All opinion polls reflect that more than 70 percent of Tunisians are keen to maintain democracy. So it's not easy to stage a coup d’etat against the wishes of this majority of Tunisians.”

Reconciliation was to prove only the first legacy of the Tunisian leader. His second could be just as important.

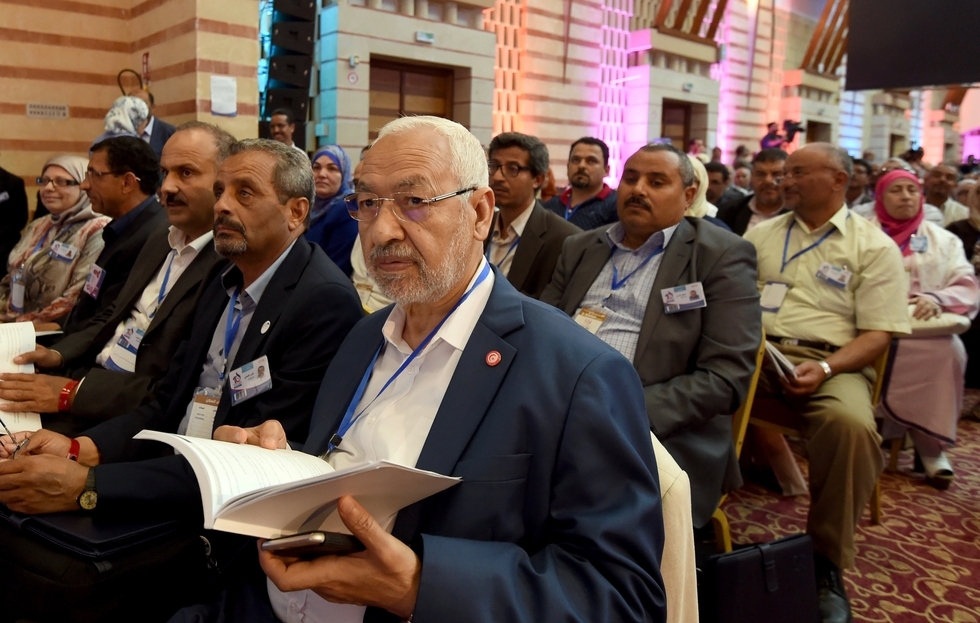

The biggest step - and the biggest risk - Ghannouchi has just taken, is the one he announced at the 10th Congress of his party last month. The man whose remarkable life has been synonymous with political Islam announced that political Islam no longer had any place in his country. While keeping its Islamic character, Ennahda was to be a purely political party, severing its connection with the dawa (or preaching) and the mosque.

Ghannouchi said: “Some religious preachers are members of our party. Once elected to parliament, they will now have to choose either to be in parliament and stop being an imam, or stay as an imam and not go to parliament.” He made clear this edict would apply as much to himself – he is a well-known preacher – as any other party activist.

Was this, we asked, his Clause 4 moment - a decision as significant as the one Tony Blair took in 1994 in Blackpool when he pushed through the abolition of the clause that committed the Labour Party to the state ownership of the means of production and launched New Labour?

Ghannouchi agreed: “Yes. We would like to promote a new Ennahda, to renew our movement and to put it into the political sphere, outside any involvement with religion. Before the revolution we were hiding in mosques, trade unions, charities, because real political activity was forbidden. But now we can be political actors openly. Why should we play politics in the mosque? We have to do politics openly in the party.”

The leader of Ennahda brushed aside claims he was abandoning Islam: “We adopted the idea of a civil party so that we can distinguish between what is sacred in Islam and what can be freely interpreted. The political field is not sacred nor immutable. It's civic, human. It's free for ijtihad or independent human reasoning… many Muslims confuse the two kinds of texts and consider all texts as sacred and untouchable and only capable of bearing one meaning. The Islamic text concerning politics is open to interpretation, and this is the field in which we now act.”

But he was abandoning political Islam, which he insists is a Western concept and, in Tunisia at least, is now conflated with the Islamic State group, known in Arabic as Daesh.

“One of the reasons that I do not need to belong to political Islam, is that Daesh is part of this political Islam. Daesh is one of the elements within political islam, so I would like to distinguish myself from Daesh. I am a Muslim democrat and they are against democracy. Daesh considers democracy as haram. There are many deep differences between us and Daesh. They are Muslim. I cannot say that they are not. But they are criminals. They are dictators. Daesh is another face of dictatorship. Our revolution is a democratic revolution, and Islamic values are compatible with democracy.”

Ghannouchi is trying to force a fundamental change in post-revolutionary Tunisian politics, abandoning the politics of identity and forcing a return to bread-and-butter issues. This, he thinks, is the only way to protect Tunisia from the chaos in the region that surrounds it.

However, the shift Ghannouchi is trying to perform leaves his party potentially vulnerable on the home and international fronts. Why should Ennahda’s social base vote for it and what implication does Ennahda’s move have for all those Islamists in Egypt, Yemen, and Syria who do not have a state to protect them?

On the home front, Ghannouchi was insouciant. Some will leave his party, he said, but he expects more to join. Ghannouchi was more cautious in his response to the international implications of his decision, for good reason. He could be accused of abandoning his troops in mid-battle.

Ennahda’s decision was a Tunisian one, he stressed. Political Islam could still work as a revolutionary model for those states where Islam is still oppressed, he conceded, but no longer in Tunisia.

Advice for Brotherhood in Egypt

For the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, he had this warning: “We advise all Islamists in the region to be more open and to work with others and to look for a consensus with others, because without national unity, without national resistance against dictatorship, freedom cannot be achieved. There needs to be a genuine reconciliation between Islamists and secularists, between Muslim and non-Muslim. Dictatorship feeds off confrontation between all parties.”

Organisational links with his Muslim Brothers have been cut: Ennahda will no longer be a member of the International Organisation of the Muslim Brotherhood, but the sheikh himself will continue to be a member of the International Union of Muslim Scholars and the European Fatwa Council. These are non-political bodies, although both are chaired by Yusuf al-Qaradawi, the most senior Muslim Brotherhood Islamic scholar.

Ghannouchi’s announcement of a break with political Islam has been praised in the West as a crucial step towards modernity. However, it has been greeted with consternation in parts of the Arab world. There is dismay that the most respected advocate of a marriage between Islam and democracy appeared to be turning his back on the movement with which he had been associated all his life.

Furthermore, there are practical fears that Ghannouchi’s change of mind could contract the public sphere in Arab despotisms where the only choice is between the dictatorship and Salafi radicalism.

Ghannouchi's associates argue that it is an experiment that applies to Tunisia only and that it is too soon to judge it. His daughter, the columnist Soumaya Ghannouchi, wrote: “The experiment we are engaged in is local and meant for Tunisian conditions. It does not necessarily apply to other experiences in the region. Each country has its own circumstances and its own problems… Ultimately, time alone will judge this experiment and will tell to what extent it is correct. So, do not rush into judging it. Negatively or positively."

New Ennahda may even change its name: it might be called the Conservative Party, and Ghannouchi did not rule out rumours he might run for the presidency himself.

Asked if there were circumstances where he might become president, he replied: "It’s not in my programme. So far."

Tunisia is the birthplace of the Arab Spring, and once again it is seeking to lead the Arab world in a fresh direction.

But can it succeed? Tunisian democracy is still fragile, as last year’s Islamic State-inspired mass shooting of British tourists at the resort town of Sousse graphically demonstrated.

Ghannouchi’s decision has been well-received in Tunis itself. Elsewhere in the country the reception is more mixed, as we discovered when we made the 200km drive south to Sidi Bouzid, the central Tunisian town where fruit-seller Mohamed Bouazizi launched the Arab Spring when he burnt himself to death in despair five years ago.

Better off before the revolution

In a cafe barely 100 metres from where Bouazizi died, we spoke to four young men drinking coffee. Only two of them had jobs. Hatem, an oil worker, told us: "There is no improvement. Nothing has changed." Hatem told us that he knew men who had travelled to join Daesh fighters in Syria and Iraq, as well as migrants heading north across the Mediterranean.

Opposite the cafe, Abdel Kader, a shoe seller, said that life was better before the revolution: "We used to find daily life less expensive than now." Abdel Kader told us that he struggled to pay the rent on the single room he shared with his wife and nine children.

Nearby we found Ali, like Mohamed Bouazizi an unlicensed trader selling fruit – melons, figs and limes - from a cart. We asked him if life had improved. "What’s the use of talking, nobody listens," he said.

He told us that he and fellow traders slept on his cart and had been better off before the revolutions.

Naoufel El Jammali, the independent MP for Sidi Bouzid, acknowledged that there were huge problems with youth unemployment: “We were speaking about these problems five years ago. But nothing has happened. People are still waiting for the government to come up with a dream. There are no opportunities for young people. They have no hope for the future. There is a temptation to be a terrorist."

The politicians have made advances, both in reconciliation and moving on from the politics of identity. The economic future, however, is still uncertain. The West lavishes leaders like Ghannouchi and Essebsi with praise but words are cheap. It has yet to come up with the money. “I think the West gave more support to democracy in Eastern Europe than in Tunisia, even though Tunisia is like a fortress guarding Europe against Daesh. If Daesh takes over Tunisia, Europe will be under real threat as we see in parts of Libya," Ghannouchi said.

This logic has so far failed to impress Western governments, who have waited for states to fail, rather than supporting states like Tunisia that appear to be finding their own solutions to their own problems.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.