New Google Cloud plans in Saudi Arabia raises dissent among shareholders

Google shareholders will push the tech giant this week to explain how it will protect digital rights as it launches a major project in Saudi Arabia which has a track record of spying on its critics.

A vote on the shareholder resolution, scheduled for Wednesday, is unlikely to pass because co-founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page, and former CEO Eric Schmidt control a majority of shareholder votes in Alphabet, Google’s parent company.

But digital rights advocates say it is a first-of-its-kind push from investors that could influence shareholders in other tech companies with cloud services in the Gulf and beyond to be more transparent about how they deal with human rights risks on specific projects.

“The entire point of it is to send out a beacon that signals that shareholders care about fundamental human rights issues,” said Jan Rydzak, investor engagement manager with Washington, DC-based Ranking Digital Rights.

'How do you do human rights due diligence in a country that has no respect for human rights?'

- Mohamad Najem, Social Media Exchange

“That, in turn, helps draw the company’s attention and the public’s attention to these issues.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Google announced in December 2020 that it was opening a “cloud region” in Dammam as part of a joint venture with state-owned oil producer Saudi Aramco to tap into demand in the kingdom estimated to be worth $10bn by 2030.

A memorandum of understanding was signed in 2018 but negotiations between two of the world’s most valuable publicly listed firms reportedly stalled after the murder of Jamal Khashoggi, when many foreign companies distanced themselves from the kingdom.

Four years later, with the deal moving forward, six investors - organised by San Francisco-based global advocacy group SumOfUs - have secured a resolution to be presented at Alphabet’s annual shareholder meeting. The company tried to get the proposal dropped from the vote, but the US Securities and Exchange Commission ruled it would move forward.

The resolution calls on Alphabet’s board of directors to commission and publicly disclose a human rights impact assessment of the Saudi cloud project and the company’s strategy to mitigate those impacts.

While the item focuses on the Saudi cloud region, it also notes similar concerns over a Google cloud region already set up in Qatar where it says security forces have interrogated social media users for tweets critical of the government.

The disclosure would be a coup for digital rights advocates in the region who say Google told them it conducted an independent assessment for the Saudi project and took steps to address issues that arose, but has refused to share any details with them for over a year.

“They never reply to our questions,” said Mohamad Najem, executive director of Social Media Exchange, a Beirut-based nonprofit defending and advocating for digital rights in the Middle East and North Africa.

“The big question that I have is: how do you do human rights due diligence in a country that has no respect for human rights? There are no elections, there are no civil liberties.”

Vital to economic growth

With a push to diversify their economies away from energy and digitise government administration processes, it should come as no surprise that cloud computing services are expanding across the Gulf.

Cloud computing provides enormous data processing power and storage volume necessary to meet the needs of both the public and private sectors.

“If you’re my customer and you’re asking me a question and it takes three seconds for the service to respond, that’s not acceptable,” Sayed Hashish, Microsoft Gulf general manager told reporters when the company launched cloud services in the UAE in 2019.

Cloud computing also underlies the development of artificial intelligence and the internet of things, key to the “smart city” initiatives across the Gulf.

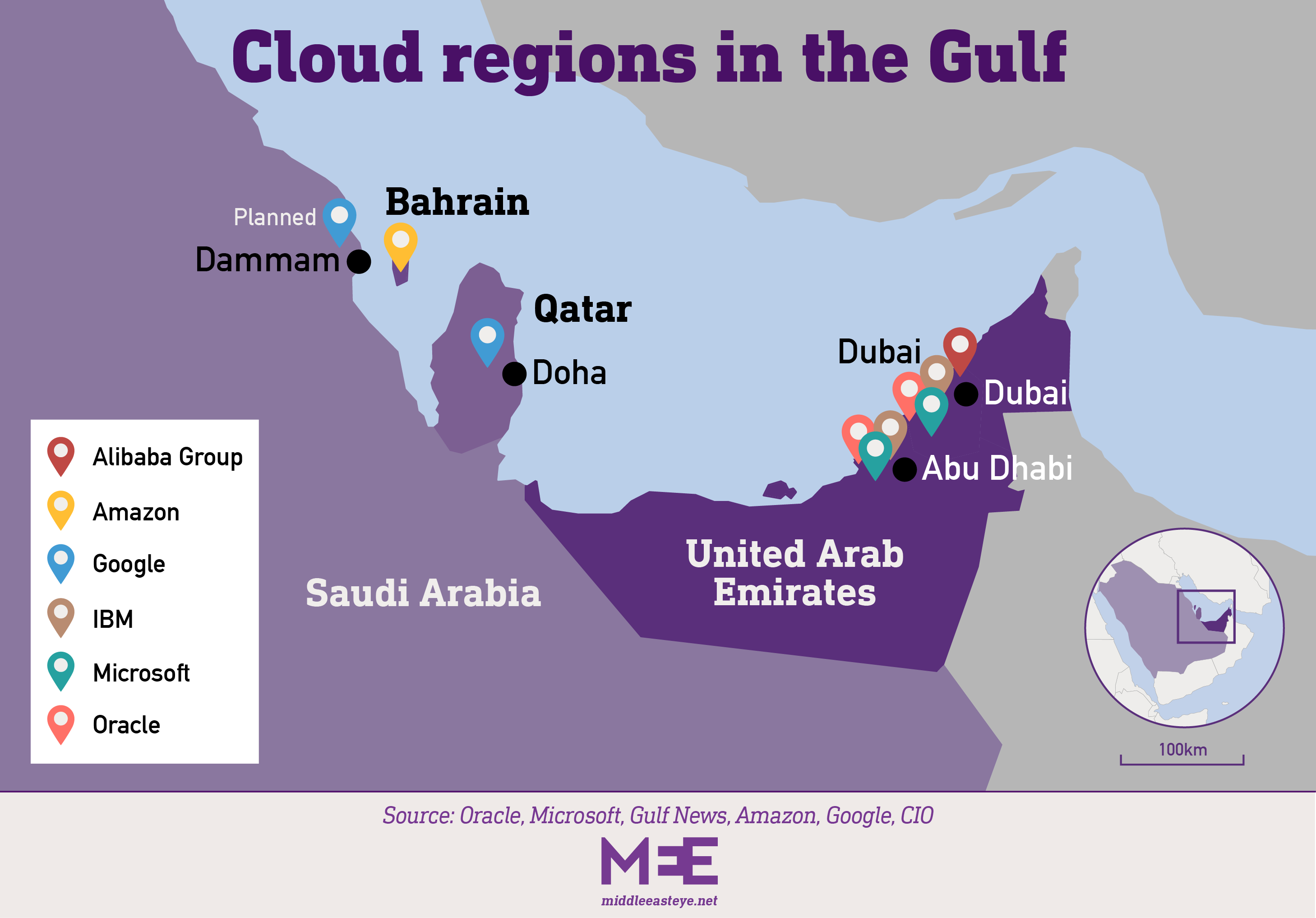

“This has fuelled the need for data centre regions and attracted Amazon Web Services, Microsoft, Google, Alibaba, IBM, and other cloud service providers to the region,” Blake Murray, an analyst with market research firm Canalys, told Middle East Eye.

Cloud deals are often structured as a win-win for governments and businesses. Typically, both will invest in needed infrastructure for the centres which create jobs, frequently with employees trained by the tech company.

The countries’ local businesses are able to grow through use of cloud computing which, in turn, means access to a new user base and revenue for the company.

MEE counts no fewer than nine cloud regions opened in Qatar, the UAE and Bahrain since 2018.

But how many of the companies that opened them conducted human rights risk assessments and mitigation plans ahead of opening their data centres is unclear.

MEE asked Microsoft and Amazon - the world’s leading cloud providers along with Google - if the firms had done either ahead of launching their Gulf cloud projects. Microsoft declined to comment. Amazon did not respond to repeated requests.

So the Google cloud region proposed for Saudi Arabia is by no means a first - and follows the cloud region it set up in Qatar - but seems to be bearing the brunt of public criticism. Why?

One reason, said Rydzak with Ranking Digital Rights, is that when Google first announced the completed deal, it suggested that Snap Inc - the parent company of Snapchat which reportedly has 17 million users in the kingdom - would be one of the companies supported by the Saudi cloud region.

That set off alarm bells for activists and observers who said the deal “directly places millions of people at risk”.

Snap responded saying that Google’s announcement hadn’t accurately described the company’s storage practices in the Middle East and that only public content would be stored regionally in order to allow users to more rapidly download that type of content.

Google also removed the reference to Snap in a section about Saudi Arabia that was part of the cloud announcement, instead emphasising that the company benefited from clouds globally and clarifying that Snap hadn’t been involved in the 2018 MoU.

But beyond the controversy over Snap that caused initial concerns, Rydzak said that the scale of Google’s operations means it attracts attention in a way that other companies don’t.

“Google is the definition of a tech behemoth. So any cloud region that it will open in a given region is going to have a ripple effect and is going to make that much more of a splash,” he said.

'Thirsty for data'

The concerns of digital rights advocates over the cloud regions in the Gulf are very simple: the UAE, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and Qatar all have a history of human rights abuses, surveillance and repression of dissidents.

Three of the governments - the UAE, Bahrain and Saudi Arabia - have recently been accused of using Pegasus, the notorious spyware made by the Israeli firm NSO Group, to target human rights defenders and dissidents within their countries and abroad.

Qatari women who have spoken out on social media against the country's guardianship laws have told MEE that they were interrogated over their posts, with some forced to remove them.

In August 2019, an anonymous Twitter account run by Qatari women which questioned why Saudi Arabia's reforms for women were outpacing their own was shut down within 24 hours after the Cyber Crime Police questioned one of the authors.

The UAE, according to a Reuters investigation, employed former US intelligence operatives for years to surveil human rights activists, journalists and political rivals as part of what was known as "Project Raven".

And Saudi Arabia is alleged to have bribed two Twitter employees who eventually shared the data of more than 6,000 Twitter users, according to a 2019 legal complaint filed in California.

Journalist Turki bin Abdulaziz al-Jasser and aid worker Abdulrahman Sadhan, who were both operating anonymous Twitter accounts critical of the Saudi government, were subsequently arrested in the kingdom.

The men were forcibly disappeared between March 2018 and February 2020 until they were allowed calls to their family, according to London-based advocacy group ALQST. Last year, Sadhan was sentenced to 20 years in prison and a 20-year travel ban.

It is one thing, say digital rights advocates, for these governments to use spyware, hire operatives or pay off employees to obtain private data about critics, and quite another thing to locate data centres within their territory.

“It is handing over the keys to the castle,” said Claire Niven, civic space researcher for the Lebanon-based Gulf Centre for Human Rights.

“They are thirsty for data, they are thirsty to get personal information and they are thirsty to do surveillance on people,” said SMEX’s Najem. “Any kind of partnership around that will lead to that.”

Among questions civil society groups have asked and still want answered is how Google - and other companies - plan to vet local employees who will have access to the data centres and how they can ensure that authorities in the Gulf countries won’t infiltrate the centres.

And if a government does manage to infiltrate a centre, how would a company rectify the situation legally in countries where they say justice systems and newly enacted data protection laws are weak?

Beyond local law and the companies’ own policies, there remains only the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, an advisory framework which is not legally binding.

'Whatever angle you look at it, it really does not make sense. It only makes sense when you think about profit'

- Marwa Fatafta, Access Now

“There are no safeguards,” said Marwa Fatafta, Middle East and North Africa policy manager for digital rights group Access Now. “Whatever angle you look at it, it really does not make sense. It only makes sense when you think about profit.”

MEE asked Google to respond to the claim that it hadn’t answered the questions of digital rights advocates, as well as how it would respond if the Saudi government, citing local law, compelled it to share user data.

A spokesperson responded: "We have a longstanding commitment to respecting the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and its implementing treaties, and to upholding the standards established in the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and in the Global Network Initiative Principles.

"We publish extensive disclosures on our human rights approach, including how we consider human rights in establishing data centers.”

Rights first, profit second

None of the advocates MEE spoke with deny that cloud computing is vital for the region or that it’s easy to find the perfect location, but they are urging companies to hold off on cloud projects until human rights are safeguarded, transparently and as much as possible.

“It’s really difficult to find one country [in the region] where there is a robust data protection framework,” said Fatafta. “But if I want to place those countries on an index, then definitely Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Bahrain would be at the very bottom of this list.

“So obviously, there’s always the question: do you advance your commercial interests over human rights? Human rights should be upheld first and then profits should come second. And that’s the commitment the companies have made publicly.”

It might feel a bit like the cloud computing ship has sailed. Google shareholders are unlikely to pass Wednesday’s resolution and there are already regions up and running in Qatar, the UAE and Bahrain.

But Rydzak with Ranking Digital Rights said the public scrutiny of the tech giant could still impact how companies already operating in the Gulf - and those planning to open cloud regions in other locations where there are human rights concerns - work in the future.

The shareholder structure in most of the other publicly traded tech companies are not like Google, meaning that shareholders would have more of a chance to pass resolutions calling for greater transparency on cloud projects, retroactively or into the future.

“If you look at how Google is responding to the pressure from human rights advocates, it's not using the competition angle at all. It's not saying, ‘Other companies have been doing this so why not us?’” he said.

“They recognise that it's not necessarily the case that the ship has sailed. It’s still very much a ship that is sailing.”

Alphabet’s annual stockholder meeting is scheduled for 9am PST on Wednesday.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.