Green hydrogen: The Gulf's next big fuel - or a load of hot air?

Qatar is the world’s second largest helium producer and traditionally exports much of its production overland via Saudi Arabia. But in July 2017, Riyadh and other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) governments imposed a blockade amid alleged ties with terrorism.

The move was not unexpected. Forced into crisis mode, Doha shut its two production plants and fell back on contingency plans to offset the expected economic hit.

“The first industry that emerged was hydrogen, so they came up with contracts to get it to market,” recalls Theodore Karasik, a senior adviser at consultancy Gulf State Analytics in Washington, DC.

Moving nimbly, Qatar reconfigured its export market, switching 25 percent of exports from GCC member UAE to East Asia, including China, Singapore and South Korea. In doing so, it became the world’s fifth largest hydrogen exporter, with sales of more than $520m by 2019.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Fast forward to 2021 and hydrogen is now being considered as an economic saviour for other GCC countries, as the global energy market transforms following the Covid-19 pandemic and worldwide moves to decarbonise.

“The entire industry is looking at the future of oil and gas, and where potential growth areas are,” says Karasik. “One of them is obviously hydrogen.”

Saudi Arabia, the world’s second-biggest oil producer, has committed to hydrogen in a big way. In February 2020 Aramco, the kingdom’s energy giant, announced it would invest $110bn in the biggest shale gas development outside the US to extract the potential fuel from the ground through fracking.

But Riyadh is not going to follow the usual route and export the product as a liquefied natural gas (LNG), which would place it in direct competition with Qatar, the world’s largest LNG exporter. Instead Riyadh will use the extracted gas to produce hydrogen.

The Aramco plan was followed in July 2020 with news that Neom, Saudi’s futuristic $500bn zero-carbon megacity, would have the “largest green hydrogen plant in the world”. The venture carries a price tag of $5bn, with a further $2bn earmarked for distribution infrastructure.

“Saudi Arabia views their future as leaders in renewable energy generation, and are quite excited about hydrogen, hoping to corner the market,” says Justin Dargin, an energy expert at Oxford University.

A greener planet

The Gulf’s moves towards hydrogen are part of the wider global de-carbonisation response to the climate crisis.

The EU has launched a Green Deal, committing Europe to being the world’s "first zero-carbon continent by 2050".

Washington, under the new administration of President Joe Biden, has similar ambitions. On Monday, US Secretary of Energy Jennifer M. Granholm announced details of the "Hydrogen Shot" programme which aims to reduce the cost of clean hydrogen by 80 percent to $1 per kilogram within a decade.

"Clean hydrogen is a game changer. It will help decarbonise high-polluting heavy-duty and industrial sectors, while delivering good-paying clean energy jobs and realizing a net-zero economy by 2050,” said Granholm.

Demand for oil in the Gulf is expected to slide as renewables gain more market share.

In a TV interview in April 2021, Mohammed bin Salman, the Saudi Crown Prince, talked of the “risk” to the Saudi economy of oil dependence and “the challenges the oil industry faces in the 40 or 50 years ahead”.

Gulf nations are likely to be the last men standing in the oil market due to the low cost in the region of oil extraction, the ongoing global need for hydrocarbons, and their dependence on oil dollars to fund their societies.

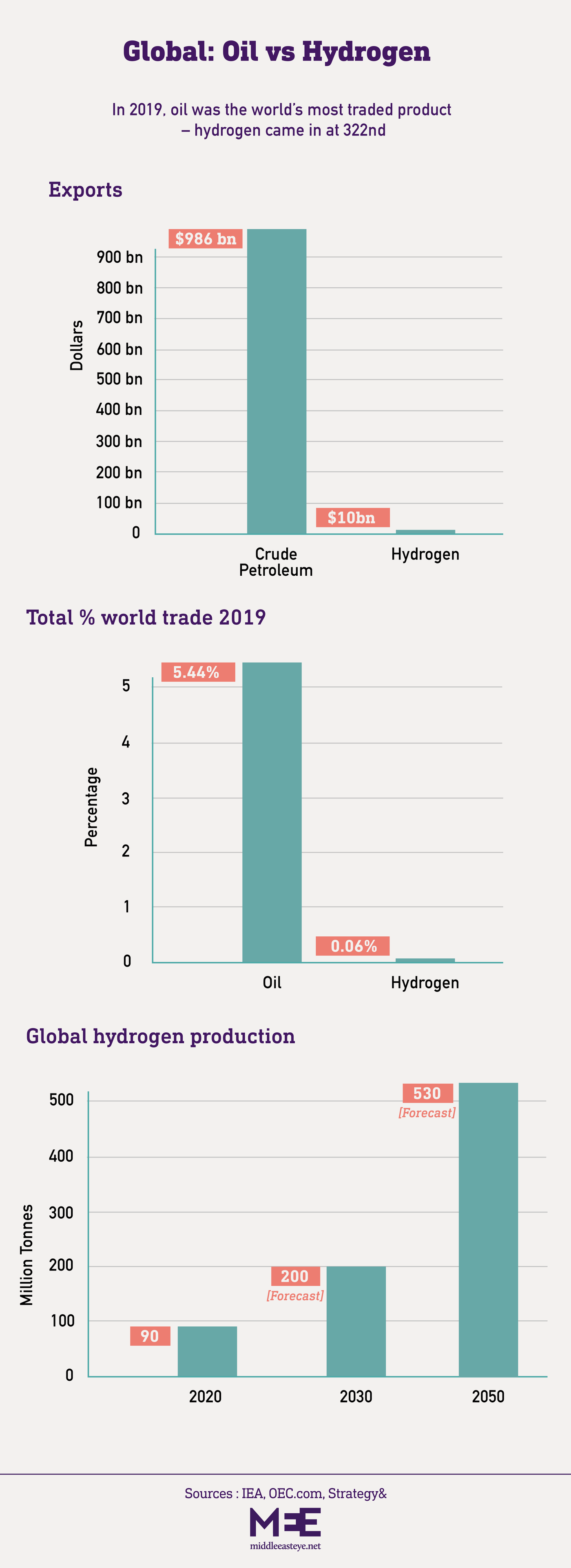

But they also need to retain a share in the overall energy market by producing renewables - including hydrogen. At the moment, that stake is tiny. While Riyadh exported $145bn of crude petroleum exports in 2019, making it the world’s number one in that market, it only managed $6.12m worth of hydrogen exports.

“Saudi Arabia and the Gulf want to keep being an energy exporter, and for the whole social model of the country to not be stressed by the energy transition,” says Daniel Scholten, assistant professor at the Faculty of Technology, Policy and Management, Delft University of Technology, in the Netherlands.

“I think they feel threatened by renewables and electrification in general.”

Crossing the funding gap

Hydrogen is the perfect fuel for the 21st century. It does not emit greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide when it is burnt, and is ideal for power generation, electric vehicles and the future of aviation among others.

But it has one fundamental problem: hydrogen rarely occurs naturally in underground deposits, so needs to be transformed from other compounds such as fossil fuels into a gas, a process called “gasification”.

Hydrogen currently comes in several varieties:

Black / brown The most environmentally damaging form of hydrogen, it is derived from black coal or lignite (brown coal)

Grey Derived from natural gas or coal, it accounts for 98 percent of hydrogen produced. But it’s bad for the planet, with carbon dioxide emissions almost equal to global aviation.

Blue More environmentally friendly, produced from natural gas, with 90 percent of carbon emissions trapped by carbon-capture storage (CCS) technology. The Gulf is investing big: last year, Saudi Arabia exported the world’s first shipment of blue hydrogen to Japan.

Green From renewable energy - but currently only 1 percent of hydrogen production is green. An estimated 24 countries currently have strategies or are working on them, including all the G7 nations, China, India and, from the MENA, Saudi Arabia, UAE and Morocco.

Pink :Produced from electrolysis powered by nuclear energy, it’s also sometimes called purple hydrogen or red hydrogen.

Yellow Still in its infancy, this is hydrogen produced through electrolysis via solar power.

Turquoise Uses a process called methane pyrolysis to produce hydrogen and solid carbon. It may have value as a low-emission hydrogen, but has not yet been produced at scale.

To achieve global net-zero carbon emissions during the next 30 years, there needs to be a global investment surge in clean electricity generation from $380bn to $3.6tn. Likewise, the global number of electric cars needs to rise from the current 2.5m to 50m by 2030, according to International Energy Agency (IEA) figures.

“It is quite staggering when you look at the projections between now and 2030 to achieve the targets,” says Kate Dourian, a non-resident fellow at the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, DC. “We’re going to need all of it, green and blue hydrogen, and renewables.”

To meet the demand, green hydrogen production will have to grow from 90 million tonnes in 2020 to more than 200 million tonnes in 2030, according to the IEA. So far only $80bn of the necessary $200bn has been invested.

“There’s a gap of $120bn between now and 2030,” says Dourian. “So for hydrogen to have a bigger market share you need government incentives, regulatory frameworks, and infrastructure investment.

“It is not much ado about nothing, but considering all the excitement about hydrogen, it is still going to have a small share of the (future) energy market.”

Obstacles in the way

Saudi Arabia and the UAE are betting on the demand for hydrogen to rise. The UAE is primarily looking at blue hydrogen, with green hydrogen plans earmarked for the aviation industry.

Germany is making regional inroads: it signed deals for hydrogen development with Morocco and Neom in June 2020 and March 2021 respectively as part of its move away from nuclear power after the Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2011.

But in the near-term, green hydrogen may not be fully viable. “We are dominated by fossil fuels, including coal power, and at the same time have an ambitious climate policy,” says Sonja Butzengeiger, managing partner at consultancy Perspectives Climate Group in Germany.

“While renewable energies capacities strongly expanded since the early 2000s, they faced the intermittency challenge. Recently, the government has woken up, and identified green hydrogen as the low or zero-carbon alternative of the future.”

Scholten says: “The Gulf will move from grey to blue to green hydrogen. Grey is not a problem, they can do it right away, and blue has hardly any emissions (85-90 percent of carbon is captured).

“But as for green hydrogen, I don’t expect too many investments in that until 2030. We have focused for a decade on solar, wind and electrification, but the hydrogen impact will become more noticeable towards the middle and end of the energy transition.

“Once coal and oil has been largely phased out, and then natural gas, hydrogen will become an important factor in the energy mix.”

Saudi Arabia and the Emirates are hedging on major technological developments for green hydrogen to be commercially - and ecologically - viable. Dargin says: “The costs for green hydrogen could potentially drop, from around $5 per kg now to $1.50/kg.”

Part of its attraction is that it makes renewable energy storage possible, an issue that has plagued solar and wind power generation, which both require batteries. In contrast, hydrogen can be turned into ammonia for transportation, which is then converted into energy at the destination market end.

Butzengeiger says: “If you transform green electricity into hydrogen, you can store it, which is a huge advantage over traditional renewables. But you really need large quantities of renewables to fuel the hydrogen economy.”

The Gulf producers have several competitive advantages. One is that they can easily produce hydrogen. Another is that they boast the world’s lowest costs for solar power generation, due to the abundance of sunshine, that will be needed for extraction.

But even the production of green hydrogen comes with four fundamental issues:

1. Land: Solar power needs energy parks to capture sunlight. If green hydrogen is to match current oil and gas revenues, then that will entail vast amounts of land, according to The Dawn of Green Hydrogen, a report by Strategy&. For the UAE and Saudi Arabia, that could mean allocating up to 20 percent of their unused land, such as desert, if they are to meet green hydrogen export demand by 2050.

2. Water usage: The creation of green hydrogen is reliant on water electrolysis, by which electricity decomposes water into hydrogen gas and oxygen. But while Strategy& argue that “GCC countries have ready access to seawater” that can be used for electrolysis, that water needs to be desalinated and then deionised, when it is purified by the removal of minerals and contaminants. To produce 1kg of green hydrogen requires nine litres of purified or deionised water.

3. Toxicity: The desalinisation process is not only energy intensive, it also produces 1.5 litres of brine for every litre of fresh water, according to a 2019 report in the Science of the Total Environment. The salt-based byproduct that results is toxic due to the chemicals used in desalinisation. The brine, which can’t be reused, is then usually dumped in the sea, which raises the temperatures of coastal waters and decreases oxygen levels, creating environmental “dead zones”, according to the report.

Each year, 50bn cubic metres of brine is produced globally from the desalinisation process - enough to coat all of the the UAE and a third of neighbouring Oman in a layer of sludge 30cm deep.

Together, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Kuwait and Qatar account for 55 percent of global desalinisation production. Further desalinisation to meet the Gulf’s hydrogen production goals will exacerbate the oxygen-starved Arabian Sea, the world’s largest marine dead zone, unless technologies improve.

4. Reliance on legacy fuels: Desalinisation is currently reliant on hydrocarbons. “Saudi Arabia is using around 20 to 25 percent of its oil production for desalinisation, which is a ridiculous amount of energy,” says Butzengeiger.

Efforts are underway to reduce the energy consumption required. Saudi Arabia’s Saline Water Conversion Corporation (SWCC) was awarded a Guinness World Record in March for “setting a global record in reducing energy consumption for desalinisation”. And Neom’s "solar dome" desalination plant, announced in January, aims to produce water at a cheaper price than conventional plants as well as create less brine.

“There are new developments in electrolysis technology that may not require purified water,” says Butzengeiger, “but none have reached commercial readiness yet. In the longer term, such solutions could allow desert countries to not have to use purified water.”

Hydrogen for home - or export?

It’s essential that the technology needed to produce green hydrogen gets up to speed. After that, Gulf producers will then face another key issue: whether they use the energy produced for their own power generation, cutting energy bills and freeing up hydrocarbons for export; or cash-in on the new hydrogen exports and leave things as they are at home.

Butzengeiger suggests Saudi Arabia use green hydrogen domestically, then export by shipping first, followed by a dedicated pipeline. “If I was [in] Riyadh, I’d use green hydrogen first within my own territory, as there is huge national demand. If there’s excess they can think of a pipeline to Europe.”

But Dargin thinks the focus will be on exports. “Saudi Arabia is committed to burnishing its credentials as a global supplier of green hydrogen.”

If Riyadh follows this second route, then it will need to address several issues including investing in a global distribution chain to meet demand; and achieving economies of scale so the price of green hydrogen can become competitive with other forms of energy.

“Saudi Arabia has first-mover advantage, so it could definitely corner the hydrogen market if it plays its cards right,” says Dargin. “It could become an absolute powerhouse if it makes this leap for the post-oil world.

“But if the Saudi policymakers fail to accurately implement its renewable energy strategies in accord with its Vision 2030, then it would not be able to achieve its broad-based macroeconomic reformation goals, which could have unintended consequences for future socio-economic stability.”

There is a much more fundamental issue facing energy production in the region. Gulf powers, especially Riyadh, have often seemed lukewarm in their commitment to renewable energy: in 2018 for instance, Riyadh announced it would invest $200bn in solar power, but six months later scrapped the project.

“If you look at the past as a blueprint for the future, they’ve not had a great success rate in follow-through for many ambitious plans,” says Dargin.

“They say they’ll generate X amount of renewable energy, then retract it, or cancel or delay projects. That said, the government has clearly telegraphed its support for the energy transition and green hydrogen as part of Neom.”

Analysts believe that UAE is more likely to move ahead with renewable projects, not least as it currently owns 70 percenr of the Gulf’s renewables capacity.

Dourian says: “The UAE has been way ahead of the curve on renewables and nuclear power. Of the planned hydrogen projects in the GCC region, the UAE is probably going to proceed with its blue and green hydrogen projects, and they normally have a record of implementing projects they announce.

“The Neom green hydrogen project has been touted as the biggest of its kind, though the partners have yet to break ground on the $5bn project.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.