The hidden hunger strike at Egypt’s Aqrab prison

CAIRO - Families of inmates held at Aqrab maximum security prison in Cairo tried to conceal their faces last week as they announced that many of their detained family members had gone on hunger strikes.

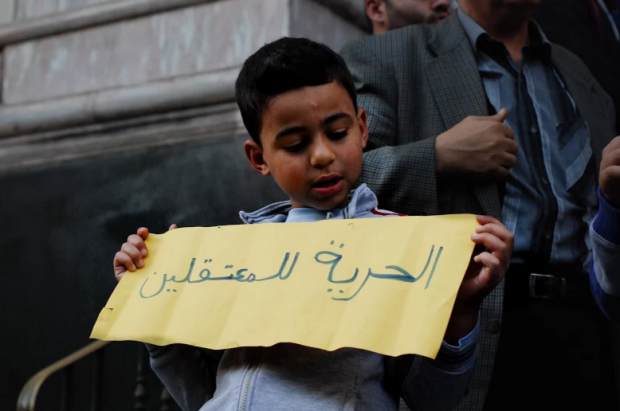

They carried signs protesting against “humiliating” visiting procedures as they picketed on the steps of the Journalists’ Syndicate in Cairo, one of the few public places in Egypt where protests are still allowed.

Across the street, police officers in uniform and civilian clothing stood watching and filming the scene with their mobile phones.

One hundred and fifty of the Aqrab detainees, who families say are all being held on political grounds, have begun full or partial hunger strikes. “This is a rough estimate,” said Aya Alaa Hosny, whose husband is one of about 1,000 detainees who have been charged with what she claims are political crimes, and are held in the Aqrab.

The families gather news from what inmates tell relations during visits.

“So for example, one family will visit their relative, he will tell them that he and five or six other people began a hunger strike, and this is how we keep count,” she said.

Prison officials have repeatedly denied to local Egyptian media that any hunger strikes are taking place.

Lawyer Mohamed Nassef told Middle East Eye that two of the detainees who are on hunger strikes, Cairo University student Amr Rabee and Sayed Aly, a leading figure of the rebellious football fan group the Ultras White Knights, are not eating because the prison is “breaking their spirits”.

Aly, for example, is still in pre-trial detention, but he is forced to wear a blue uniform like those who have already been charged, his lawyer said.

That might appear to be a small matter, but it does come down to the details of what clothes they are allowed to wear or not, sanitation, and because “their bodies don’t see the sun,” he said.

In early December, a number of detainees went on a brief hunger strike after officials refused to allow winter clothes and blankets inside the prison.

One anonymous prisoner was able to get out a letter in which he wrote that the detained are “the living dead,” confined in “inhumane” conditions, prohibited from changing their clothes, wearing slippers or leaving their dark, poorly ventilated cells.

The state-backed National Council for Human Rights (NCHR) made a planned official visit to the prison in early January and later released a statement that denied allegations of torture and sexual assault against the prisoners.

Rights workers and the detainees’ families criticised the statement, while families maintained that prison administrators make only temporary improvements before NCHR visits, and that conditions return to their usual state shortly after.

Families have demanded that prison officials who they claim carry out torture in the prison be held responsible.

Human Rights Monitor, an independent human rights group, said that it has documented cases of torture in which prisoners were hung by their arms for several hours, electrocuted in sensitive areas and severely beaten. The organisation also said that it has documented cases of officers raping detainees.

Radwa Khairy, whose father is imprisoned, said her family arrived at Aqrab at 2am in order to be one of the 20 or 30 families allowed to visit inmates.

“But we were number 50, because so many families had slept there from the night before,” Khairy said.

Her two sisters didn’t want to leave as they had not seen their father since 23 January, just before visits were halted prior to the fifth anniversary of the 25 January 2011 revolution.

“They went to speak to the police officers, who told them to leave … so they began chanting,” Khairy told MEE. “The officers were annoyed and one of them slapped Yomna in the face and another struck Rahma,” she said, referring to her sisters.

“The bruises were so bad, Rahma couldn’t go to school the next day.”

Khairy said that if they had been lucky enough to be granted a five-to-seven minute visit, they could have seen their father only through a glass window and have talked only with phones “that sometimes don’t work”.

For many families, the price they pay for visits is not just emotionally costly, but materially as well, especially for those who make the trip from other regions.

“The trip can cost almost 900 pounds [$115] for those who come from faraway governorates,” Hosny said, adding that families also have to find money to meet the costs of living inside the prison.

“Prison food prices have gone up by 40 percent,” she said, which is almost impossible for some families to cover, especially those whose breadwinners are detained.

Hosny said families found out “by coincidence” last week that they could visit inmates again after the 25 January closure, when two women who went to the prison to leave some money for a relative were told they could go in.

“They asked if they could tell the rest of us, but then we were surprised to find that they only allow the first 20 to 30 families inside, and now they are making people come a day early to register for visits,” she said.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.