How France ignored European promises and armed Sisi's Egypt

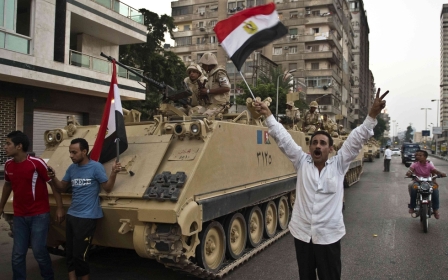

In his five years in office, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has been able to count on France as a trustworthy arms supplier during one of the most troubled periods in his country’s history.

A report published by several NGOs - including the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), the Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies, the League of Human Rights and the Observatory of Weaponry (OBSARM) – on Monday claimed that “the French state and several French companies have participated in the bloody Egyptian repression of the last five years”.

On 12 August that year - two days before the Egyptian army’s crackdown on protesters in Rabaa al-Adawiya Square, during which more than 800 people were killed - French company Manurhin, a leading manufacturer of ammunition-producing machinery, was due to deliver a machine to manufacture 20mm and 40mm cartridges, which can be used for both rubber-coated steel bullets and tear gas canisters, to the Egyptian government.

However, just before the state-of-the-art equipment was due to be delivered, French customs blocked the transfer, following the escalation of demonstrations sparked by the coup against President Mohamed Morsi.

French and European arms exports to Egypt were suspended for a few months, only to start anew after Sisi took office, with considerable attention paid to a large-scale project meant to modernise the Egyptian army - with the support of substantial Saudi funding.

French companies have also proven to be a great support in providing systems to monitor Egyptians’ daily lives

The Egyptian army purchased German U214 submarines, Russian Mig-29 fighter jets and S-350 anti-aircraft missiles, but French weapons manufacturers’ sales also boomed at the time, with the orders of Rafale fighter jets, a FREMM frigate, three Gowind corvettes, and hundreds of armoured vehicles.

Sisi’s Egypt even helped France after French company DCNS - now known as Naval Group - found itself mired in a crisis with Moscow due to sanctions that led to France’s refusal to deliver two Mistral helicopter carriers to the Russian navy. Egypt swooped in to claim the two huge ships, worth more than a billion euros, effectively saving DCNS.

Moreover, French companies have also proven to be a great support in providing systems to monitor Egyptians’ daily lives.

In their report, the NGOs said by “equipping the Egyptian security and repression services with powerful digital tools, [France and its weapons manufacturers] have thereby participated in setting up an Orwellian surveillance and control architecture, aimed at cracking down all attempts at dissent and mobilisation”.

France's fourth largest customer

On 21 August, 2013, the European Union called on its member states, including France, to suspend their arms transfers to Egypt in order to prevent them from being used for domestic repression purposes.

But paradoxically, France has never sold and delivered so many weapons to Egypt in such a short time period as since 2011. The country became France’s fourth-largest customer between 2007 and 2016.

According to the FIDH, at least eight French companies, encouraged by successive governments, took advantage of the situation in Egypt to reap record profits. Between 2010 and 2016, French arms deliveries to Egypt rose from $46m to $1.5bn.

Between 2010 and 2016, French arms deliveries to Egypt rose from $46m to $1.5bn

“While the European Council announced the termination of military and surveillance equipment exports in order to sanction the dictatorial drift in Egypt, France took the opportunity to gain market share and achieve record exports,” said FIDH's president, Dimitris Christopoulos.

Helicopter carriers and espionage equipment

In their relations with Egypt, French defence companies can be classified into three categories.

The first includes heavy equipment suppliers whose weapons do not belong to police arsenals, such as Naval Group, which has supplied two helicopter carriers, a frigate and a corvette, and is preparing to assemble three of them in Egypt: Dassault, with its Rafale; Sagem, with its laser-guided bombs or its Patroller; and Thales UAV, with observation or designation pods for fighter aircraft (Reco-NG and Talios).

The second category groups together companies that sell military equipment that can be used for "pacification" and anti-terrorist operations. Renault Trucks Defence - now known as Arquus - sold several hundred Sherpa tanks to former Egyptian leader Hosni Mubarak’s regime and later pursued cooperation with Sisi.

The third type of French company involved is the more pernicious category of suppliers of espionage, surveillance and internet censorship equipment, used to tap phones and shape public opinion on social networks.

The FIDH report, which draws in part from OBSARM’s work, identifies companies that have provided Egyptian law enforcement and secret services with technologies for individual surveillance (Amesys/Nexa/AM Systems), mass interception (Suneris/Ercom), individual data collection (Idemia) and crowd control.

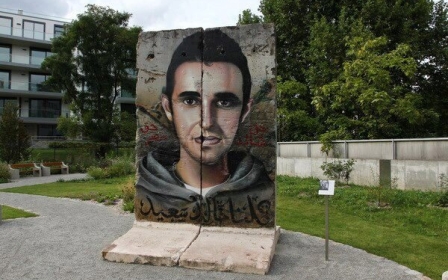

‘While the 2011 Egyptian revolution and the Arab Spring had been carried out by means of an ultraconnected 'Facebook generation’ that mobilized crowds online, France is now participating in the crushing of this generation’

- Bahey Eddin Hassan, Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies

“While the 2011 Egyptian revolution and the Arab Spring had been carried out by means of an ultraconnected ‘Facebook generation’ that mobilised crowds online, France is now participating in the crushing of this generation through the implementation of an Orwellian surveillance and control system aimed at nipping in the bud any expression of protest,” said Bahey Eddin Hassan, president of the Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies, which also collaborated on the FIDH report.

How is the French government involved?

But why does the report associate the French state with what could merely have been opportunistic business opportunities for French private companies?

In addition to the state being a shareholder in several major French defence groups such as Thales or Safran, when financial packages cause problems, the French president or prime minister will usually be the one who can override the Egyptian government’s solvency issues to guarantee large contracts.

The French government has paid half the deposits for at least three major contracts: the Rafale aircrafts deal, and the MBDA missiles and DCNS ships sales – amounting to $6.5bn.

Paris is directly involved due to the obligatory political validation of weapons sales through the granting of export licences through the Interministerial Commission for the Study of Exports of War Material (CIEEMG).

The CIEEMG is the only authority that assesses whether it is possible to sell military equipment to a third country. Its primary function is to prevent the dissemination of French technologies and ward off copy-cats.

It can also block sales in order to prevent specific countries from gaining access to state-of-the-art technologies if doing so would shift the balance of power with France and its allies.

Finally, it is designed to prevent the misuse of military technology by a third country. The CIEEMG issues licences product by product, so that they can be ready for purchase during calls for tender, then issues another license for export in the event of a purchase order.

The first three representatives have discretionary powers over exports, while the others may issue advisory opinions which will be taken into account in the final decision.

The system in place is evidence of the French government’s degree of involvement in the military equipment export process.

In publishing this report, the FIDH “calls on the French government to immediately terminate these deadly exports and to set up a parliamentary inquiry into arms deliveries to Egypt since 2013".

More generally, the signatories of the report called once again for an overhaul of the French system for the control of arms and surveillance equipment exports, rendered ineffective by its opacity and dependence on the executive branch.

- The article is based on an a translation of a story that was originally published by Middle East Eye's French website.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.