How a Saudi travel company bankrupted an Indian migrant worker

When Ahmed Abdul Majeed left India for Saudi Arabia in June 1981, he was excited to start a new chapter in his life.

He had already begun a career as a travel agent in Hyderabad after graduating with distinction in mathematics.

It was there that he was spotted by recruitment agents working on behalf of Saudi companies.

“Al Tayyar Travel came and hired me as a senior sales executive in June 1981,” Abdul Majeed says, referring to the popular Saudi-based agency.

He moved to Riyadh, beginning what would become a four-decade career in the Saudi capital.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

That chapter would later come to a devastating end.

It would involve Abdul Majeed being threatened with arrest and ordered to work for free, having his passport taken away and being forced to sell his family's assets to cover corporate debts that had nothing to do with him.

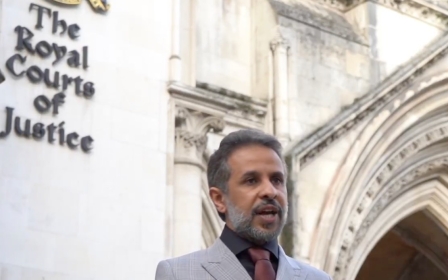

The 67-year-old spoke to Middle East Eye in his first interview about his ordeal.

“I really enjoyed my job. It involved operations, sales and marketing - I was an all-rounder,” he recounts, adding that he had managed a team of more than 20 at times.

“I was famous for my high-end clientele, like royal families and embassies.”

Ritz-Carlton purge

Abdul Majeed built a personal relationship with the founder and owner of the company, Saudi tycoon Nasser al-Tayyar.

“We used to talk, always - not only business, sometimes personal. He used to talk about his family and I would talk to him about mine.”

Everything was going well in Abdul Majeed's career until it all changed on 4 November 2017.

Tayyar, along with 200 other powerful Saudi businessmen, royals and officials were arrested and taken to the Ritz-Carlton in Riyadh in a purge that described as an “anti-corruption” drive.

The drive, led by newly-appointed Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, saw Saudi elites probed and detained until they agreed to hand over proportions of their assets.

Prince Mutaib bin Abdullah, son of the late King Abdullah and once seen as a possible crown prince, was tortured and beaten, sources told MEE at the time.

One Saudi general was reportedly tortured to death.

Saudi officials said around $106bn was seized from 381 individuals, though the figure is disputed.

'Every night, I would wake up and cry. You have no idea what I have suffered'

- Ahmed Abdul Majeed

Tayyar, like many other detained elites, reached a settlement with the Saudi government. Shortly after the Ritz-Carlton purge, in April 2019, Al Tayyar was rebranded as Seera Group.

The new company replaced its senior staff and Tayyar no longer served on the board.

Abdul Majeed said he spoke to Tayyar upon his release.

“He told me frankly, 'You can no longer stay here because this company has been taken over by MBS,'” Abdul Majeed recalled, using the acronym for the crown prince.

“We had a chat for almost an hour. [Tayyar] said, ‘It’s better for you to think things over because there is new management.’ And he was right.”

Things changed rapidly under the new management staff, including workflows, recruitment, personnel and salary structures, Abdul Majeed said.

Senior figures linked to Saudi Arabia's Public Investment Fund (PIF) became involved in running the company, he added.

'Every night, I would cry'

For Abdul Majeed, everything came to a head when the Covid-19 pandemic struck.

“In March 2020, they decided to terminate the contract of many foreign staff members. I was one of them.”

Despite his four decades of service, no reason was given for the termination.

Abdul Majeed accepted his fate and decided he would go back to India to take care of his wife, who was due to undergo critical surgery.

“The real ordeal started after the termination. I’m still suffering today.”

He explained that Seera Group took his passport and said he would be required to work without pay to help recover overdue balances owed by the company's clients.

Out of goodwill, he continued to work for two months, calling clients and chasing up payments. Many clients - such as hotels and airlines - were unable to pay due to the crippling impact of the pandemic.

“Seera Group told me I needed to clear all the debts. I told them that it was not my job. I'm not the owner of the company. I'm not a shareholder. I'm just an employee.

“It's not my duty to collect the payments of corporate accounts. It's the duty of the finance department. If they can’t get the payments as per the contract, it's the duty of the legal department to sue the client,” he says.

His protestations were to no avail.

Seera Group told him that clients owed $100,000 and that he could not return to India until it was paid. He soon realised he would have to cover the amount from his own pocket.

He said the situation felt akin to modern-day slavery.

“They told me that if I didn’t make the payment, I would be behind bars for the rest of my life.”

“Every night, I would wake up and cry. You have no idea what I have suffered.”

Scared and threatened, Abdul Majeed called his son in India and asked him to begin the process of selling their family home in Hyderabad.

“We made a big loss on the sale because we needed the money immediately. I also took loans from several family members.”

'My demand is justice'

After selling much of his family’s assets and taking multiple loans, Abdul Majeed managed to gather $100,000.

Once he paid it, his passport was finally handed over to him and he was given permission to leave - but not before being dealt a final blow.

“I had to pay for my own flight ticket home. Flight tickets are part of the contract, the employer must provide it,” he said.

After four decades of service - ending in six months of unpaid labour, threats and forced indebtedness - Abdul Majeed returned to India in September 2020.

He returned with no money to his name and a deep sense of injustice.

Abdul Majeed began writing letters and emails to Seera Group, the PIF and the office of Mohammed bin Salman. He received no responses.

He reached out to Indian Prime Minister Narendara Modi’s office, which forwarded his case to the Indian embassy in Riyadh. The embassy asked Seera Group to resolve the matter, but the travel agency did not reply.

The Indian government considered the matter closed.

Abdul Majeed then moved to Chicago, where one of his sons, Ahmed Abdelumer, works as a delivery driver.

In the United States, he sought justice by reaching out to Saudi ambassador Reema bint Bandar Al Saud and even visited the Saudi embassy in Washington, but received no reply.

Three months ago, Abdul Majeed’s case was highlighted in a letter to US Secretary of State Antony Blinken, signed by six members of Congress.

The letter addressed issues of human trafficking and mistreatment of migrant workers in Gulf countries.

“[Abdul Majeed] was repeatedly denied the ability to leave the country despite multiple requests to tend to the declining health of his wife, ultimately paying the company dues out of his own pocket in order to finally return home,” the lawmakers, including Ilhan Omar, told Blinken.

MEE reached out to Seera Group and the Saudi embassy in London but received no response.

Four years after being bankrupted by one of the largest travel agencies in the Middle East, Abdul Majeed is still searching for answers.

“My demand is justice,” he says. “I'm not going to keep quiet. I will continue to fight for justice. Everyone must know the true face of MBS.”

“They must not repeat this mistake again with any other migrant worker.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.