'I'd rather die in my house': How Egypt’s 'successful' Sinai campaign starves locals

Egypt's latest campaign to crush a violent militant insurgency in the Sinai peninsula is causing immense suffering among civilians including dire shortages of food in the northern city of Arish, locals say.

The operation has resulted in a blockade of the Sinai’s largest city, with food, medicine and gas now prevented from reaching the city’s roughly 180,000 inhabitants.

Sawsan, a student at Arish University, has been spending every morning since 9 February waiting in long queues for army-owned food trucks, waiting to buy any type of vegetable available, before heading home to cook for her young brothers.

Following the beginning of Comprehensive Operation Sinai 2018, on 12 February, only three types of food cart has been allowed to enter Arish, the capital of North Sinai province.

Some are controlled by the army, others are brought by well-off traders and the rest are sent by rich businessmen.

The army sends in only two or three cars a day, which leads to huge congestion and overcrowding, and the police protect the cars by firing warning shots into the air.

The second type usually arrive only after negotiations and bribes, and leads to civilians being subjected to inflated prices, due to a lack of supervision from the authorities.

The third type are gifted in the form of charity, and products are given away for free, often leading to stampedes and people getting injured in the process.

But while the Sinai operation has been widely praised in Egyptian media and in society, the situation in Arish has deteriorated since the first day of the campaign - a factor which has been totally ignored by the national media.

Hours after the start of the campaign, dozens of families from southern Arish province - where most of the air strikes and shelling are taking place - left for the relative safety of the city itself.

Salim’s family were among those first internally displaced residents.

For the first couple of days we still had some food that we had brought from our farm land, but it has run out. So we are now like the rest of them

- Salim, Arish resident

They left behind their two-storey house after the marble factory in which most of the male relatives worked was evacuated and abandoned by the army, which detained two members of the family.

“More than four men are now with no income, plus they wanted to arrest one of our cousins and didn’t find him at first, so they took his wife,” Salim explains.

“We called him and he turned himself in, and then she was let go,” he added, saying that his cousin was accused of being a member of the Muslim Brotherhood.

Now with a reduced income and a shortage of goods in the city, food is running out, he says.

“For the first couple of days we still had some food that we had brought from our farmland, but it has run out. So we are now like the rest of them.”

After his cousin was arrested, he said the family has been viewed as traitors.

“We have been shamed enough, and even branded traitors in the city, just because one of us was arrested.”

Shop closures

Even owners of small grocers, poultry shops, fish markets, and private bakeries have closed their business, due to a lack of goods.

Emad, the owner of a poultry shop, told MEE that after only a few days into the Egyptian military offensive, he was nearly out of supplies.

“By the fourth day of the campaign, most of the mature chicken in storage was sold. Even the bones [used to make soup] were gone.

“We only had some young chickens who are small and not worth eating yet, but we had to prepare them for selling because fodder carts were not allowed in.”

We are for the end of terrorism, but are not for the siege of thousands of people and imposing starvation

- Hisham, banker

As has now become routine for the city dwellers, each morning, Emad sends his family members off to various outlets across the city, those that remain open.

“In normal times, I wouldn’t want my wife standing in line for ages, but I hear when they see a woman carrying a baby they might give her four pots of yoghurt instead of two.”

Hisham, a married bank teller with two children, has moved out of his own home and returned to his parent’s house, on the western side of the city, in search of food.

“My kids were hungry, so we went to my father’s hoping that they had some food.”

He supports the military campaign, Hisham is keen to stress, but is against the effect it is having on civilians.

“We are for the end of terrorism, but are not for the siege of thousands of people and imposing starvation.

I would rather die in my house than go down and humiliate myself in those food lines. We are not Syria or Iraq

- Hisham, banker

“I would rather die in my house than go down and humiliate myself in those food lines. We are not Syria or Iraq,” Hisham tells MEE.

“When the blockade is over, I will leave Arish for good. I don't want my daughters to be raised hearing the sound of air strikes and gunfire,” he adds.

“I don't want to sound anti-army, but the state has completely failed to manage the crisis.”

Getting a fair share

Others have made their peace with the food lines, but demanded better organisation from the authorities, to avoid the humiliation of stampedes and queuing for hours.

Saed, a pensioner who used to work as a teacher, does not mind standing in line, he says, as long they are organised, and as long everyone gets their fair share.

On the chaos of the food distribution, Saed told MEE: “Once I stood in front of the bakery since 6am, waiting to buy some bread, but after an hour and a half of queuing, the oven closed, as they had ran out of gas.”

But the dough was already prepared, so the worker hauled it to another oven, as if carrying a dead body. Dozens of people followed the dough, he recalls, in a scene reminiscent of a funeral procession.

“The regime is losing points by humiliating the people of Arish. If you are fighting guerrilla soldiers, you have to win the sympathy of the locals,” he says.

“The situation now reminds me of the numbers of young men in North Sinai who were radicalised in 2005 and 2006, after State Security started to torture whole families and humiliate their women in detention centres,” he adds, warning that the ill-treatment of residents will actually just lead to increased sympathy for the militants.

Heba, a student at the North Sinai University, is no longer going to campus, as the university announced it would suspend all classes until the military operation is over.

“Are we supposed to postpone our life and our future?” she asks. “Did they suddenly decide we have to fight terrorism instead?”

Masoma is an Egyptian journalist from Arish who works for a privately owned daily newspaper in Cairo. Every day, since the beginning of the campaign, she awakes at 7am to a new statement from the army spokesperson, on the successes of the operation, which she then has to write up.

The ways these statements are written and how they [the army] order the media to publish them and highlight them is very fascistic

- Ma'soma, journalist

She says this entails little more than receiving the statement from copy and pasting the statements, from the "propaganda" office of the army.

“The ways these statements are written and how they [the army] order the media to publish them and highlight them is very fascistic,” she says.

She points out that there are lists of sources that the army “ordered its registered journalists to call” to receive further analyses on the statements.

“Sometimes the army wants to highlight a certain aspect, for example the release of suspects or that food rations have been distributed.

“The list of sources to contact includes mainly ex-officers, all known to have an ultra-nationalist stance, but who are vocal in the media as ‘military or strategic experts.’”

MEE attempted to call one of the generals listed, Ali Hefzy, but he declined to comment, saying that he “must get the approval of the high-ranking officials first.”

Deprived from living a decent life

“People there [in Arish] are deprived from living a decent life, proper food, and education, while here in Cairo and Giza, people and officials are celebrating this ‘so-called’ war on terrorism by songs and dancing,” Ma’soma says.

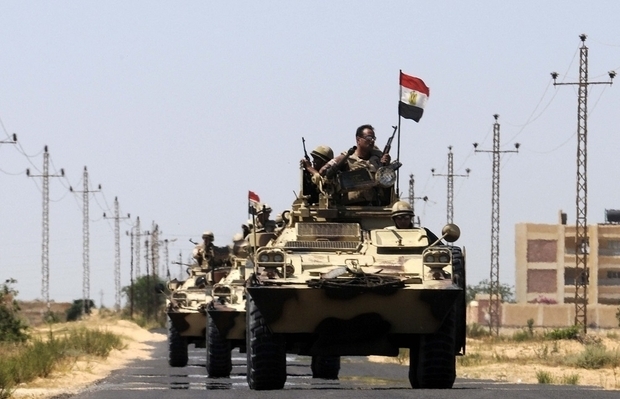

Indeed, newspaper and TV channels in Egypt have been rejoicing, with nationalistic, pro-military slogans and features, and promotions lauding the special forces and armoured cars.

“So far the military said that it has killed 105 suspects. Who were they? What were their backgrounds? Did they all have a card that read “Islamic State”? Could it be that some of them were civilians?” asks Ma’soma.

“We will never know, as long as we live in the state of fear, where the general knows more than the normal civilian.”

On the way home, Sawsan is content, having managed to buy two kilos of tomatoes, two pots of yogurts and five loaves of bread. She sees a homeless man who had found a dead sheep, cutting it up and packing its meat in a plastic bag.

“This is what Arish has become. The proud people started to look for food in the piles of trash and to wait in lines for rations. We are on the brink of starvation, and no one seems to care.”

* For security reasons, all names have been changed

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.