Islamic State: Bosnians' sluggish repatriation from Syria leaves families in limbo

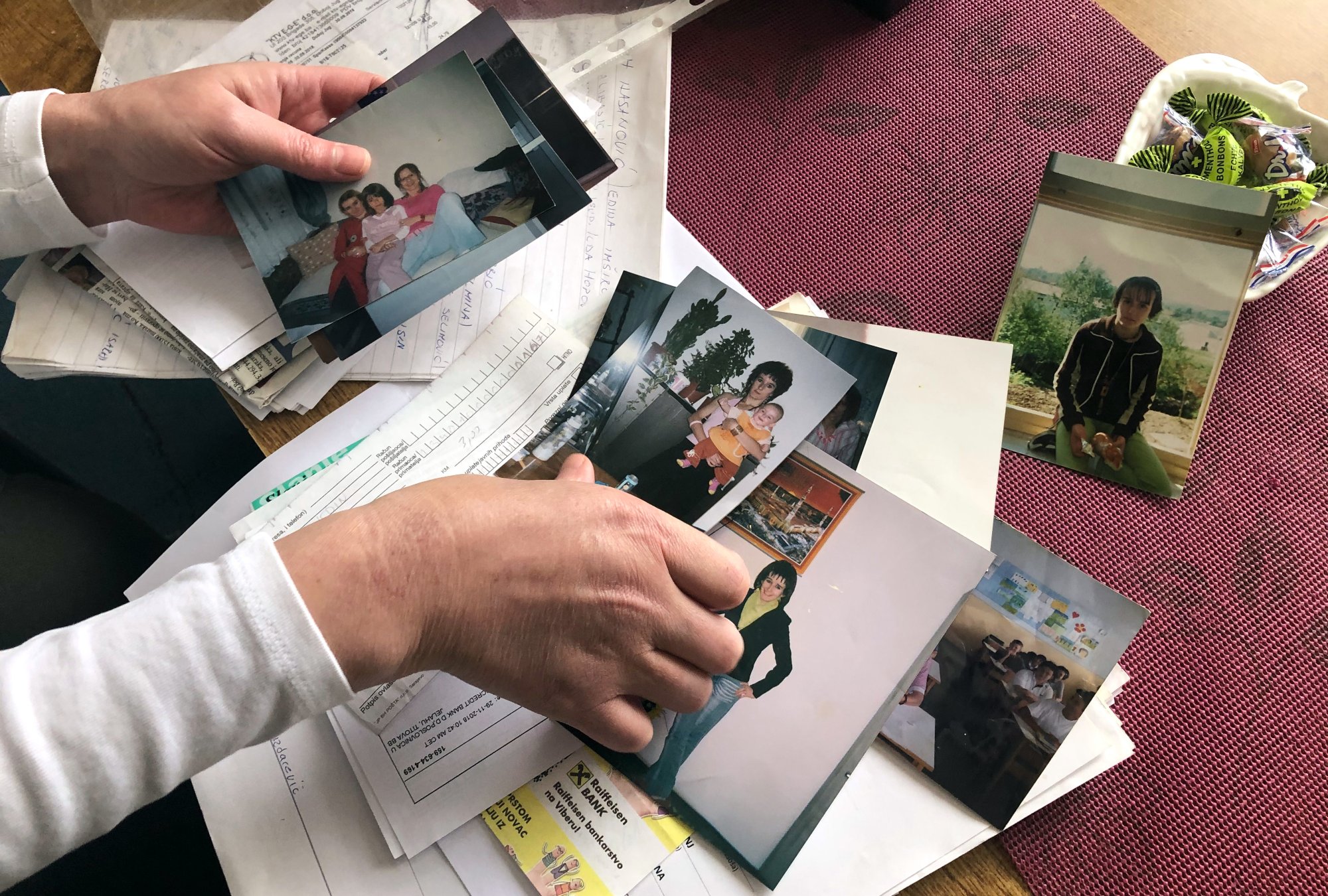

Alema Dolamic has never met her sister's two youngest children, but in the past three years the 40-year-old has fought tirelessly to bring her nieces and nephew, two of whom were born in Syria in 2015 and 2016, to their mother country, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH).

Eight years ago, Dolamic's younger sister, Adela, got married in their central Bosnian hometown of Tesanj to a man whom she followed to Syria that same year.

Taking along her then-eight-year-old daughter, Adela - as told by her sister - believed she was going to a world where all Muslims would live united under the so-called Islamic State (IS), led by religious rules and laws, something her husband died for in 2017.

Between 2014 and 2019, IS controlled large areas of land in Syria and Iraq. While it has since lost control of these territories, the fate of foreigners detained in Kurdish-run camps, the majority of whom are women and children, has remained a lingering question for many countries.

In the last few years, Dolamic has put everything else aside to focus on bringing her sister and three children home, leading hundreds of family members of what she believes are around 85 Bosnian citizens still held in Kurdish-run camps in Syria.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Fearful of the level of trauma they have already endured, Dolamic keeps thinking about the impact on children of lives spent almost exclusively in detention camp tents.

"Efforts should be put into taking out at least the children," she told Middle East Eye. "They did not choose where they were born, nor did they choose their parents."

International human rights advocates, Syrian Kurds who run the crowded camps, as well as US officials have repeatedly urged countries to repatriate their citizens held in inhuman or degrading conditions and ensure those suspected of having actively participated in IS are tried in courts in their home countries.

But Dolamic has been fighting an uphill battle with Bosnian authorities, as the return of suspected IS-affiliated citizens from Syria is not solely a humanitarian matter.

For those who are repatriated to Bosnia after years in overcrowded camps, troubles likely won't end there. Unfavourable economic and social conditions await those who return to the country, which has suffered from corruption and mass emigration as a result of the 1992-95 war.

About a half of Bosnia and Herzegovina's citizens are Muslim, some practising believers and others not. However, several hundred fighters of Arab origins, a formation known as el-Mujahideen, came to central Bosnia during the 1992-95 war. It is believed that the roots of radical understanding of Islam that made dozens of Bosnian families leave for foreign battlefields like Syria two decades later lie in their legacy, as well as the influence of foreign and foreign-educated preachers in subsequent years.

With its own specific history distinct from other European countries facing the same dilemma, Bosnia is struggling to figure out what its strategy should be to handle the thorny issue of repatriation.

Security concerns

In March, Human Rights Watch estimated that around 43,000 foreigners linked to IS, including some 27,500 children, were still held in camps run by regional authorities in northeast Syria, two years after the fall of the IS "caliphate," "often with the explicit or implicit consent of their countries of nationality".

For its part, Bosnia has organised only one official repatriation, of 25 of its citizens - 12 children, six women, and seven men - on 19 December 2019. All of the men were arrested on the spot.

A Bosnian Security Ministry official said at the time that at least 100 citizens have yet to be brought back.

However, a source within the ministry told MEE that the government cannot "speak of concrete numbers [of people] until we have completed lists for return," adding that Sarajevo needed to take legal, diplomatic, social, health and security factors into consideration for the repatriation and reintegration of citizens.

Such statements, however, are frustrating for relatives like Dolamic.

"Since 2018, security ministers have changed three times, and each time we are back at the beginning," she said. "Each time, [the families] had to send the information again, who is out there, how many children they have."

After collaborating with Bosnian intelligence and security agencies for months prior to the 2019 repatriation, and being told that her sister would be part of that first group, Dolamic was disappointed to learn she wouldn't be seeing Adela at the Sarajevo airport.

"I provided so much information and did so many things. They know everything about my sister. I see no reason for her to be there. She left the Islamic State on her own will," Dolamic argued.

While the humanitarian and security situations in the camps have been a cause for concern, for Washington DC-based security and radicalisation expert for the Balkans Adrian Shtuni, a number of technical, diplomatic and political factors beyond those tied to the Covid-19 pandemic complicate and delay the repatriation of Bosnian citizens.

Shtuni told MEE that there are security concerns both in the areas surrounding the Kurdish internally displaced people (IDP) camps and prisons as well as inside them, due to continued armed hostilities and ongoing attacks by IS militants.

"Another issue is that al-Hol and al-Roj IDP camps [where most Bosnian women and children are held] are controlled and operated by Kurdish militias that are non-state actors," he told MEE. "Many among those held in Kurdish IDP camps and prisons do not possess valid travel documents, especially children born in the conflict theatre, whose citizenship claims may have to be established through DNA tests."

Meanwhile, he said, political factors are also at play.

"Many governments in Europe and elsewhere have refused to take back adults from Syria, limiting repatriations to orphaned children under the age of 12," Shtuni said. "Simply put, they don't want to take the political risk of repatriating someone who may carry out terrorist attacks at home.

"Nevertheless, all of the above represent valid but not insurmountable obstacles."

Bosnia and Herzegovina has so far convicted 28 men of "terrorism" for their fighting in Syria, with sentences ranging from one to seven years of prison. None of the six women who were repatriated in the first group were tried, in contrast to other European countries that have sentenced women for joining IS.

"The case of each adult returnee should be investigated based on evidence, not stereotypical assumptions," Shtuni said. "Countries of the western Balkans would do well not to exclude returnees from criminal responsibility based on gender considerations. Stereotypical assumptions that all the women who travelled to Syria were victims are inaccurate."

Vulnerable children

Sarajevo-based lawyer Mirsad Crnovrsanin, who previously worked within the terrorism unit of the state prosecution and later as defence attorney for one returnee, sees the absence of trials for women as justifiable primarily due to the potentially negative effect on their children.

Crnovrsanin argued that the country needs to take an individualised approach in treating radicalised women and children in order to properly reintegrate them in Bosnian society.

"Bosnia and Herzegovina has a good legal framework. However, as a country in transition that suffered from the destruction of war, it represents a fertile ground for existing and new forms of radicalism and extremism," he said.

The lawyer said that the lesser sentences for the men returnees compared to other countries are in place because "this complex phenomena cannot be suppressed by processing and strict sanctioning".

Unlike other countries, which have pushed forth legal and security policies above all, Bosnia and Herzegovina has officially prioritised a reintegration programme for those who return, as well as enabling prevention mechanisms, with one key link in the chain being social work centres. However, political leaders have baulked at the idea of openly supporting repatriations, worried about the potential risks involved.

Experts agree the deradicalisation of women and children will largely depend on individual motivation to abandon their IS ideologies. Different countries have set up programmes that include psychological treatment, religious re-education, job training, and economic assistance for returnees, Shtuni said, adding that there are no one-size-fits-all models and Bosnia and Herzegovina will need to build programmes based on its specific cultural context, traditions, circumstances and available resources.

Dolamic has already talked with Tesanj's own social centre, whose two employees went through training on the matter, about what kind of support her sister and children might receive if they are repatriated.

Sabrija Kavazovic, director of Tesanj's centre for social work, told MEE that in the two-day training last year, she was presented with the experiences of colleagues who worked with the small 2019 group of returnees.

What she expects to be the hardest hurdle is the legal and social integration of the children, some of whom are likely to not even speak Bosnian fluently.

"As far as we are informed, there should be 14 persons [returning to Tesanj] - three women and the rest are children," she said. "They are returning from a world that we find strange. Children are traumatised. Psychologists will have to work alongside us to help them adapt here and go to school.

"We don't have experience with this, but I hope it will all go well," Kavazovic added. "Until they return and we talk to them, we won't know in which direction to work with them."

For most dealing with the issue, the fate of children looms large.

"Children returnees are to be considered primarily as victims and treated with special care, protecting their rights and prioritising their best interest," Shtuni argued.

For women, however, Shtuni warned that it would not be unexpected that some of them continue to display beliefs concurrent with the ideology of the Islamic State.

"There is no X-ray machine that can tell you when someone is deradicalised. Some people will renounce violent extremist ideologies and adopt constructive social behaviours. Yet, some others will be less successful," he said.

The impact of trauma inflicted on the children is still hard to quantify, however, as some, like Shtuni, estimate that the older ones are further at risk of being brainwashed with IS ideology with each passing day in the Syrian camps.

"Simply put, further delays in repatriation, especially of children, would be wrong and short-sighted from both a humanitarian and security perspective," Shtuni concluded. "It is all but certain that the longer children are kept in these camps, the higher the chances they will be traumatised and radicalised, making their rehabilitation and reintegration process longer and harder."

Meanwhile, Dolamic's anger has only grown the longer she has had to fight for her family to be brought back.

"She [Adela] did make a mistake, but my God, there are bigger crimes than that," she said. "[The children] suffer while being innocent, having no idea what life is, what a house is."

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.