Israel celebrates its Independence Day more fractured than ever

Haaretz is Israel’s liberal Jewish newspaper; Makor Rishon, the journal of the religious right and the settlers. Together they represent the two ideological extremes of the country’s Hebrew-language media.

Yet somehow, for Israel’s 73rd Independence Day, falling on 15 April this year in the Hebrew calendar, their message to readers was nearly identical: Israel is more divided than ever.

Makor Rishon relied on a survey it published showing that 50 percent of secular Israeli Jews think that Israel should be, above all, a democracy, while only 10 percent think that being a Jewish country is paramount.

Compare that with religious and ultra-Orthodox Israeli Jews, of whom more than 80 percent said being a Jewish state is most important (zero percent said being a democracy is most important).

Fewer than four percent of secular Jewish Israelis said that what most connects them with the country is the Bible, compared with over 75 percent of religious and ultra-Orthodox Jews who said so.

The front cover of the Haaretz holiday supplement featured a map of Israel boldly labelled “DIVIDED”. Even without a survey, the Haaretz portrayal of today’s society is just like the one in Makor Rishon.

The clearest manifestation of this rupture is, of course, the ongoing political crisis.

Three weeks ago, Israel went to the polls again – the fourth time in two years. This is without precedent in the post-World War II era, but as yet there is no sign that the crisis is any closer to a resolution.

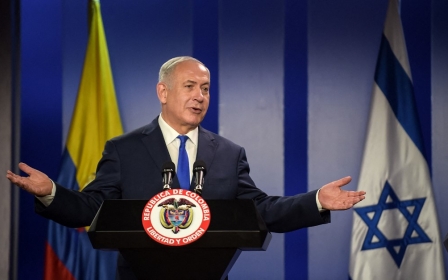

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s Likud won more votes than any of its rivals, yet remains a relatively small party with only 30 of 120 seats in parliament. The next-largest party, centre-right Yesh Atid (There is a Future), won 17, while 11 other parties won between four and nine seats apiece.

More members of parliament recommended Netanyahu than anyone else as their choice to be tasked by President Reuven Rivlin with forming a government. Yet a week after he got the nod, Netanyahu’s prospects for enlisting the 61 seats he needs to form a government for the sixth time appear doubtful.

Coalition building

To do so this time, Netanyahu needs an impossible coalition. It would have to include the right-wing religious-nationalist Jewish parties, whose official political stance is anti-Arab and anti-Islamic. It would also have to include the Islamist Raam headed by Mansour Abbas - a party ideologically, though not organisationally, allied with the Muslim Brotherhood camp, at least in terms of external support.

If such a coalition were ultimately to be assembled, it would undoubtedly by the strangest one in Israel’s history. Something like a coalition between Sinn Fein and UKIP.

And if Netanyahu fails, the baton apparently passes to Yair Lapid of Yesh Atid. After a decade in politics, former journalist Lapid has begun to seem like the “responsible adult” of the political centre.

Most Israelis believe that neither Netanyahu nor Lapid will succeed in forming a government, in which case in August of 2021, they will return to the polls for the fifth time

He, in turn, would have a tough time.

To assemble his coalition of at least 61, Lapid would need to include two distinctly rightist parties (Naftali Bennett’s Yamina and Gideon Saar’s New Hope) that support annexing the occupied West Bank and expanding the settlements; another right-wing party, Yisrael Beiteinu, considered moderate by today’s Israeli standards but headed by Avigdor Lieberman, known for his history of incendiary anti-Arab incitement; two centrist parties, Yesh Atid and Defence Minister Benny Gantz’s Blue and White, exponents of the old Israeli establishment; two leftist Jewish parties, Labor and Meretz, who gained some support in the last election with positions relatively more radical than in the past; and two parties representing the Palestinian Arab minority in Israel – the Joint List and Raam.

Even if Lapid somehow managed to tamp down the clash of egos among the leaders of these parties and form a government, it is difficult to see how such very different parties could put together a shared platform for governance. No wonder most Israelis believe that neither Netanyahu nor Lapid will succeed in forming a government, in which case in August of 2021, they will return to the polls for the fifth time in under three years.

This exercise has begun to seem normal. The last time the legislature approved an annual budget was in early 2018. Since then, Israel has been operating on budgetary autopilot, which means an extension of the most recent formally approved budget.

Netanyahu centre stage

The culprit customarily singled out as the explanation for this profound political crisis is Netanyahu himself. That is certainly accurate. The only common thread uniting the parties that might ultimately join a right-centre-left government under Lapid is their opposition to the prime minister.

Contrary to what Netanyahu’s supporters claim, however, this opposition is beyond the purely personal. An indicted Netanyahu is currently in court. In testimony begun last week, the editor of the country’s largest news website described how the company’s owner ordered him daily, and sometimes more than once a day, to publish items supportive of Netanyahu and spike anything detrimental. Meanwhile, the court heard, Netanyahu sought to use his own power to advance the business interests of that owner.

So long as Netanyahu remains on trial, his growing attacks on the judicial system and the rule of law will continue to mount.

During the last 12 consecutive years of his rule, Netanyahu has created a regime built mainly around personal loyalty to himself. This regime is conspicuous in every aspect of Israeli public life: in the media, cultural affairs, the military and the national security agencies, the judicial system, the police, the health system.

With the advent of Covid-19, this became particularly noticeable. Netanyahu has been the one announcing to Israelis, during near-daily television appearances, whether they should stay home or go out, how much money he would give them, when and what for. He positioned the vaccine campaign, a notable success in Israel, as if he himself had invented the vaccine and purchased it with his own money.

Lately this phenomenon appears to be impacting Israel’s confrontation with Iran. With the explosion at the Natanz uranium enrichment facility and the attacks on Iranian shipping, it is hard not to suspect a link to Netanyahu’s desperate efforts to remain in power.

Against this backdrop, with Netanyahu morphing into an Israeli version of Recep Tayyip Erdogan or Viktor Orban, one can understand the rise of a broad anti-Netanyahu protest movement during the past year. Tens of thousands of Israelis took to the streets every week to demand his resignation; it is already the longest such protest movement in Israel’s history.

The public pressure is what ultimately led yet again to early elections and drove someone like Saar, a prominent right-winger long viewed as Netanyahu’s heir within Likud, to come out openly against the prime minister prior to the last election and then afterwards, too.

The data show that most of the public shares this loathing for Netanyahu. Even given his tremendous personal power, and the fact that major media follow his orders or at least are afraid to oppose him, in the last four elections he has been unable to achieve the outright governing majority he seeks.

This last time, as an example, the parties personally committed to Netanyahu received 52 seats. The parties expressing opposition to him received 68: a large majority.

Netanyahu has essentially mortgaged all of Israeli politics for his own personal purposes. Instead of a rift between right and left, the schism has become for or against Netanyahu. It is largely his doing that the country is so paralysed politically, unable to address the big questions: a free market or social responsibility? A Palestinian state or annexation?

Splintered camps

Yet there is no certainty whatsoever that, even if Netanyahu were to step aside, Israeli politics would return to normal. The country’s current political crisis, on the eve of Independence Day, goes beyond even Netanyahu. You could say that Israel is not just split into left and right, secular and religious, Jews and Arabs, as per Haaretz and Makor Rishon. Internally, the groups also lack a consensus on how to move forward.

After Donald Trump’s “Deal of the Century” failed and the idea of annexation was taken off the agenda, the folks on the religious right lost their central narrative. They still want to continue the occupation and the settlements, of course, but now they have no defined aim comparable to annexation. Not coincidentally, the right has split into two parties: the fascist Religious Zionism party headed by Bezalel Smotrich, and Bennett’s Yamina, with a number of lesser schisms, too.

The religious and ultra-Orthodox camp is also fractured when it comes to questions like LGBTQ rights and the status of women, as well as with respect to its relationship with the state. Lapid defined himself for years as a man of the centre, neither a rightist nor a leftist.

Now he realises that this neutral stance is no longer tenable, given the depth of the ongoing polarisation in Israeli politics, and he is looking for new directions. The Jewish left understands that it must deepen its partnership with the Palestinian Arab public within Israel, but doesn’t know how.

The pessimists will say that this fracturing will ultimately lead to even worse disintegration and to greater tension between these groups, and perhaps even to violence

The Palestinian public itself, in Israel, is severely riven, with Raam’s departure from the collective. In contrast to the very clear line taken by the Joint List, which positions itself as part of the Israeli left, despite all the challenges of partnering with Jewish-Zionist allies, Raam announced concisely that “it is in neither the left’s nor the right’s pocket” and is prepared to support Netanyahu, under certain conditions – something unthinkable as recently as a few months ago.

Raam has also held to a strict conservative line as evidenced in a harsh attack on the alleged “secularism” of the Joint List, mainly over issues of LGBTQ+. After the Palestinian minority in Israel had seemed to be succeeding in unifying under one party, the Joint List, and had garnered its greatest electoral total in last year’s election, with 15 seats, now this public also appears to be definitively split.

In a speech he gave in 2015, Rivlin categorised Israel as “four tribes”: the secular, the ultra-Orthodox, the national religious, and the Arabs. This was an admission that the attempt to produce some kind of essential “Israeli” identity, unifying all the different groups living in the country, had failed.

Now it seems that even the four basic groups are internally conflicted and unable to agree on consensual action. The optimists will say that this crisis is an opportunity to build an Israeli politics on healthier foundations, going back to the most basic issues, including the occupation and Jewish superiority. The pessimists will say that this fracturing will ultimately lead to even worse disintegration and to greater tension between these groups, and perhaps even to violence.

What is certainly clear is that Israel has had happier Independence Days than this one.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.