Israel’s sabotage op shows Iranian nukes are back on the agenda

The six mysterious explosions and fires across Iran in recent days indicate that Israel and the United States’ intelligence services have relaunched their campaign to sabotage Iran’s nuclear programme.

Over two weeks, incidents were reported in an X-ray laboratory in Tehran, a missile and explosives storage facility near a military base in Parchin, east of the capital, in power stations in the cities of Shiraz and Ahvaz, a factory in Baqershahr, and the Natanz nuclear site.

Not all of them may be the work of intelligence agents. Quite possibly the incidents in Tehran, Parchin, Shiraz and Baqershahr are accidents, and the result of poor maintenance and negligence.

It’s not clear what was the reason for the Ahvaz explosion, but the city and Khuzestan province it lies in are known to be a centre of dissent. In the past, some local guerrilla groups, mostly from the local Arab population, have been involved in attacks against the government and its symbols.

But it seems that the huge explosion followed by a fire in Natanz was the work of professionals who knew what they were looking for.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The targets were a few buildings above ground that served as workshops and laboratories to assemble and test newly developed centrifuges to enrich uranium. The centrifuges are known as IR-8, and they can spin faster, more effectively and waste less spent materials, and their rotors are more balanced.

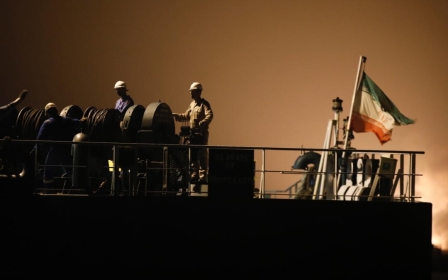

Natanz, located 300km south of the capital, is a small city and site of Iran’s largest uranium enrichment plant.

The site was dug 30 metres underground and its entrance fortified and concealed to defend it from air attacks.

Building the site and hiding it without informing the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) was in violation of Iran’s international obligations to the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and agreements with the IAEA.

The site was discovered in 2002 during a news conference of Iranian exile and opposition groups. But the sources of information came from the Israeli intelligence.

After lying, denying and playing the “cat and mouse” game typical of its behaviour patterns when it comes to the nuclear programme, Iran admitted the existence of the site. It also claimed that the plant is aimed to enrich uranium for its nuclear reactor built by Russia, to generate electricity in the port city of Bushehr.

The centrifuges installed in the plant there were old models dating back to the 60s, which were illegally purchased in the 90s from the smuggling network of Dr Abdul Qader Khan, the “father” of Pakistan’s nuclear bomb.

Systematic campaign

After the revelations, Iran put Natanz’s plant under IAEA inspections and has since then allowed international inspectors to visit the site. Yet a few years later, in 2009, American, Israeli and British intelligence found out that in the village of Fordow, near the holy city of Qom, Iran had once again constructed a secret uranium enrichment plant.

It was much smaller, better fortified and deeper - 90 metres underground. The size and location of the Fordow site, according to western intelligence estimates, was tailormade to house centrifuges for military purposes. It was there that Iran began a series of tests to develop more advanced centrifuges than the old, ingenious Pakistani-made ones.

Between 2002 and 2013 Iran was subjected to a systematic campaign organised by Israeli and American intelligence communities, in cooperation with many of their western counterparts, to slow down and delay Iran’s nuclear programme, which was suspected to be of a military nature.

The campaign included sabotaging nuclear and missile sites, assassinating five scientists specialising in weaponisation (which is the last and most important phase of assembling a bomb), cyber warfare using viruses such as Stuxnet to damage computers, and duping Iranian purchasing networks to buy flawed equipment.

Mossad and the CIA also took advantage of Iran’s many ethnic minorities, such as Kurds, Arabs, Azeris and Baluchis, within which were and still are people unhappy with Tehran’s centralised system dominated by the Shia majority.

The agencies formed secret ties with some underground and guerrilla elements among these ethnic groups, recruited agents and assisted them with weapons and intelligence.

But the most lethal weapon was the international economic sanctions issued by the UN Security Council in 2006. The sanctions crippled the Iranian economy and eventually in 2013 its religious, political and military leadership led by Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei caved in to the pressure.

Against the initial stubborn approach of its leader, Iran was forced to come to the negotiating table. Two years later, despite strong opposition from Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, six world powers signed the deal with Iran to curb its nuclear ambitions, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). In return, Iran was promised that the sanctions would be gradually lifted.

Yet Netanyahu continued to lambast the deal, describing it as a “Swiss cheese with holes”.

Netanyahu’s fortunes were reversed when Donald Trump entered the White House in January 2017. Sixteen months later, with a tail wind from Netanyahu, Trump ordered the US to unilaterally pull out of the deal and re-impose economic sanctions.

All the other five signatory members - the UK, France, Germany, Russia and China - continued to adhere to the deal. For a year or so Iran, too, respected the JCPOA.

Rivals preoccupied

In the meantime, Tehran found itself preoccupied with involvement in the wars in Syria, Iraq and Yemen, and its ambitious plan for regional hegemony. Iran deployed troops and Shia mercenaries and militias in Syria, armed Lebanon’s Hezbollah with missiles and began confronting Israel.

Israel, too, was busier and more concerned with erasing the Iranian presence on its Lebanese and Syria borders, and embarked on a military campaign using its air force to attack Iran’s positions and its allied fighters.

It seemed that the nuclear issue had been put on the back burner. But in 2019, realising that the US sanctions were hurting again and the economy was not recovering, Iranian leaders decided to take action. They started to violate the nuclear deal, but without fully withdrawing from it.

Iran increased the quantity and level of the allowed enriched uranium according to the JCPOA from 3.5 percent to 5 percent, and began the work on the advanced centrifuges.

Iran is not breaking out fully of the deal because it hopes Trump will not be re-elected this November, and a Democratic administration led by Joe Biden will rejoin the JCPOA.

Nevertheless, Israel and US security and intelligence chiefs feared that Iran’s work on the new sophisticated centrifuges would bring it closer to the nuclear threshold, and decided to act.

Israel and US security and intelligence chiefs feared that Iran’s work on the new sophisticated centrifuges would bring it closer to the nuclear threshold, and decided to act

The sabotage in Natanz is probably the ultimate evidence. Iranian officials said that the blast was a result of a powerful bomb installed in the buildings.

For a few days Israel maintained silence, neither confirming nor denying who was responsible for the explosion. But then earlier this week the New York Times cited a “senior Middle East intelligence” source saying that indeed Israel was behind the attack, confirming that the blast was the work of a powerful bomb.

Former Defence Minister Avigdor Lieberman rushed to say that he knew where the leak came from, and advised Netanyahu to shut the source up, adding that whoever was behind the leak was already preparing for primaries in the right-wing Likud party.

One doesn’t have to be an intelligence expert in codes to decipher Lieberman’s hints. He meant to say that Yossi Cohen, the head of Mossad, was NYT’s source. Cohen, who admires Netanyahu and holds similar right-wing views, agreed this week to renew his term by another year to June 2021.

The Natanz explosion is just one more setback for Iran. Its economy is a shambles, and compounded by the coronavirus pandemic, has encouraged the Iranian public (especially its ethnic minorities) to begin to express their frustrations.

Publicly little is seen due to authorities’ zero tolerance for such dissent. Nationwide protests in November were violently cracked down on, with hundreds reportedly killed.

Either way, as we have seen in the past, it will be difficult for Iranian leaders to ignore the fact that such serious incidents as witnessed in recent days - whether intentional or accidental - undermine morale and are a psychological blow.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.