Israel-Palestine: Who controls the Egypt-Gaza Rafah crossing?

Palestinians in the besieged Gaza Strip have only one gateway to the outside world that is not directly controlled by Israel: the Rafah border crossing with Egypt.

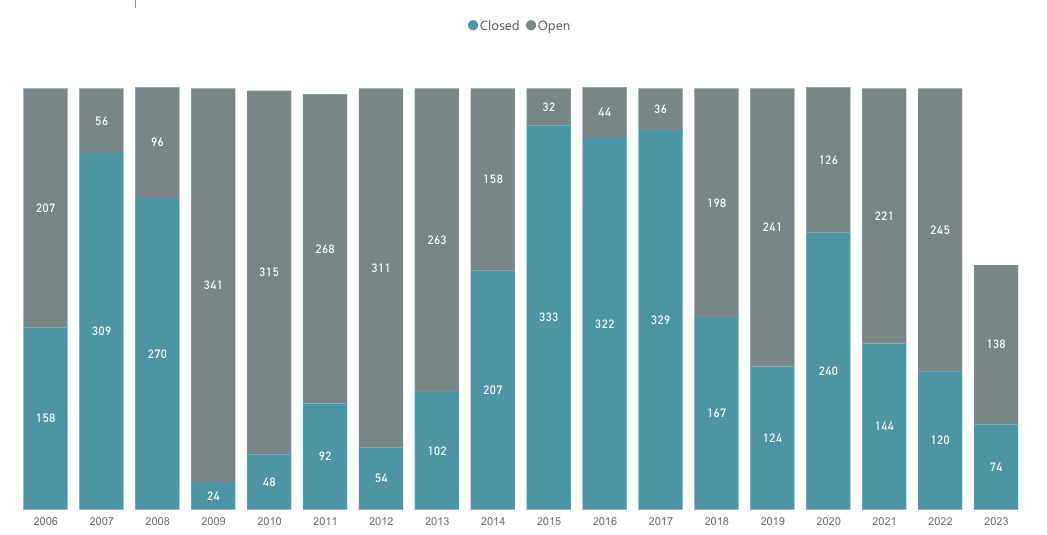

It's a "lifeline" for Palestinians that Cairo has tightly controlled for years, limiting how long it's kept open down to as few as 32 days in a single year at some points.

The restrictions are part of the Israeli-led blockade on Gaza imposed since 2007, which has turned the Palestinian enclave into what some call an "open-air prison".

But since Israel launched a brutal bombing campaign on Gaza last month, Egypt has failed to facilitate the entry of life-saving aid to more than 2.2 million people, citing Israeli restrictions.

The first aid convoy, comprising 20 trucks, finally entered on 21 October - 13 days after the start of the assault. Prior to that, Egypt said that the crossing was officially open but inoperable due to the Israeli bombardment on both sides of the boundary, which destroyed parts of the crossing and the roads surrounding it.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The amount of daily aid allowed to enter Gaza, estimated to be around 31 trucks a day before a four-day truce was agreed last week, represented only a “drop in the ocean” compared to the average 500 daily humanitarian aid trucks that used to enter the strip, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO).

Under the Hamas-Israel temporary truce deal reached on Thursday, around 200 trucks were allowed to enter each day since.

Middle East Eye breaks down the historical and legal context for Egypt and Israel's restrictions on the Rafah crossing, and how it became a contributor to the siege on the Gaza Strip over the years.

'Siege policy'

Israel announced a "total siege" on Gaza on 9 October, barring entry of fuel, food, medicine and other essential commodities for the besieged Gaza population.

Both the Israeli-controlled Beit Hanoun (Erez) crossing, used for pedestrian movement, and Karem Abu Salem (Kerem Shalom), used f0r goods, were shut in a move widely decried by UN officials and experts as a form of "collective punishment".

The siege coincided with a heavy bombardment campaign and a land incursion that killed nearly 15,000 Palestinians in 50 days, including at least 6,150 children. Thousands more are missing under the rubble.

The attacks started on 7 October following a Hamas-led Palestinian assault into southern Israel that killed around 1,200 people, most of them civilians.

Meanwhile, Israeli fighter jets bombed the Rafah crossing while imposing stringent conditions on Egypt regarding the entry of humanitarian convoys.

Aid trucks slated for entry into Gaza via Rafah have to first drive for a distance of more than 100 km (62 miles) to the Nitzana crossing between Egypt and Israel for security screening, then return to Rafah for another check before entering Gaza.

Cindy McCain, the UN World Food Programme (WFP) executive director, described the restrictions and inspection conditions imposed by the Israeli government as "insane". The Egyptian foreign ministry also criticised the measures, saying they significantly delay the delivery of crucial aid.

But even prior to the current conflict, the Rafah crossing had been closed regularly by Egypt, particularly since the 2007 Israeli blockade.

UN data shows that the worst period for closures was between 2015 and 2017, when the crossing was open for an average of only three days per month.

It was mostly open in the five years prior to that, while it averaged a closure around every other day since 2018.

Rights groups have denounced both Israel and Egypt for the closures of the crossing.

“Israel, with Egypt’s help, has turned Gaza into an open-air prison,” said Omar Shakir, Israel and Palestine director at Human Rights Watch.

The Israeli human rights group B'tselem said that Egypt is "a partner in Israel's siege policy".

Both rights groups describe the siege, including the closures of Rafah crossing, as amounting to the crime against humanity of apartheid.

Historical context

The history and legal framework of the Rafah crossing dates back more than 40 years ago.

Located on the borders of southern Gaza with Egypt, the crossing first became an international boundary following Israel’s 1982 withdrawal from Egypt's Sinai Peninsula.

Under the 1979 Israel-Egypt peace treaty, Israel returned Sinai to Egyptian control but maintained its occupation of Gaza.

'They cannot go to Egypt, and they cannot go back to the northern Gaza Strip... Gaza is almost completely destroyed and uninhabitable'

- Lorenzo Navone, lecturer

A new border was then created between Gaza and Egypt, splitting the city of Rafah into two parts; one Egyptian and another Palestinian. This split came into effect after the 1982 Israeli withdrawal from Sinai.

The crossing was then controlled by the Israeli airport authority on the Palestinian side, while the Egyptian army controlled it on their end.

The 1979 treaty also established the Philadelphi Route, known as the Philadelphi Corridor, a 14 km long (100 metre wide) buffer zone along the entire boundary between Gaza and Egypt, from the Mediterranean sea to the Karem Abu Salem border crossing with Israel. The treaty gave Israel control over the route.

The Oslo Accords of 1993 and 1995, signed between Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO), paved the way for the creation of the Palestinian Authority (PA), which accordingly was granted limited self-governance of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank.

Meanwhile, the Gaza-Jericho Agreement of 1994 established a new system of joint control over Rafah crossing, with Israel retaining most control over the access of persons, and the PA sharing some control over security and screening.

However, in January 2001, Israel seized full control of the crossing in the wake of the second Palestinian Intifada. In December the same year, Israeli forces destroyed Yasser Arafat International Airport in Gaza, the only airport in Palestinian territories, established only three years earlier by virtue of the Oslo Accords.

On 1 September 2005, Egypt and Israel signed the agreement on the deployment of a designated force of border guards along the border in the Rafah area, also known as the Philadelphi Accord.

The agreement authorised Egypt to deploy 750 border guards along the Philadelphi route to patrol the border on the Egyptian side. The Egyptian force would not be deployed for military purposes and would not change the status of the route as a demilitarised buffer zone. However, its designated purpose was for “the combating of terrorism and infiltration across the border".

Later in the same month, Israel implemented what it called “a disengagement plan” from Gaza, withdrawing its forces and settlers from the Palestinian territory, as its continued presence there was seen as a security liability. Israel also closed the Rafah crossing for a couple of months.

On 15 November 2005, Israel and the PA signed the Agreement on Movement and Access (AMA) for joint control of the crossing, which maintained Israel's authority to close the border and restrict the access of individuals.

The agreement restricted the use of the crossing to Palestinian ID card holders and other categories of foreigners, including "diplomats, foreign investors, foreign representatives of recognised international organisations and humanitarian cases" based on prior notification to Israel and the PA. Notification to Israel, according to the principles attached to the agreement, would be sent 48 hours in advance of planned travel.

The AMA stated that monitors from the EU Border Assistance Mission Rafah (EUBAM Rafah) would have oversight over the border operations.

The crossing was reopened on 25 November 2005, when Israel handed control of the Rafah crossing to the PA, with restricted movement for Palestinians who were allowed to use it only nine and a half hours a day, in accordance with the AMA.

Up until the 2007 blockade, Israel remained in control of six out of seven Gaza crossings, in addition to its exclusive control over the strip’s air and maritime space, along with access to utilities including water, electricity and telecommunications.

Only two months after the PA was handed over control of the crossing, Hamas won the 2006 legislative elections, ousting its rival Fatah from power.

Later that year, a Hamas-led an incursion into the Karem Abu Salem crossing killed two Israeli soldiers and captured another, Gilad Shalit.

In retaliation, Israel bombed Gaza, closed the Rafah crossing and barred EUBAM Rafah staff from accessing it.

By June 2007, Palestinian political tensions turned deadly, with Hamas wrestling control of the strip from Fatah and becoming the de facto ruler there.

Subsequently, Israel suspended the AMA and the Rafah crossing came under joint control of Hamas and Egypt.

'Random and unpredictable'

Israel then imposed a land, sea and air blockade on Gaza, severely restricting the movement of people and goods.

The siege included the closure of all Gaza’s crossings except for Rafah, Beit Hanoun and Karem Abu Salem crossings. The Rafah crossing was closed for most of 2007 and 2008, severely impacting the humanitarian situation in the strip.

Lorenzo Navone, a lecturer at the University of Strasbourg who was based in north Sinai to conduct research on the Rafah crossing between 2008 and 2011, said that the opening of the crossing was a “random and unpredictable” process.

“People from the Palestinian diaspora who came to visit their relatives had to wait for lengthy periods, sometimes months, to be given access,” he told Middle East Eye.

A corresponding humanitarian crisis manifested itself when Palestinian armed forces destroyed part of the wall along the Rafah border in January 2008, allowing nearly half the population of Gaza to cross into Egypt seeking to access food and supplies. Then-Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak ordered troops not to attack the Palestinians.

The following years saw more openings of the crossings for Palestinians, particularly following the 2011 Egyptian popular revolution that forced President Mubarak to step down and culminated in the election in 2012 of President Mohamed Morsi, whose platform vowed to ease the siege on Gaza.

However, Morsi was overthrown a year later in a coup by his defence minister Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, under whose administration the Rafah crossing was closed again.

'People from the Palestinian diaspora who came to visit their relatives had to wait for lengthy periods, sometimes months, to be given access'

- Lorenzo Navone, lecturer

Over the past ten years, since Sisi’s 2013 coup, northern Sinai has become off-limits for independent media, researchers and civil society as the government imposed a blackout on the area during its campaign against an Islamic State-affiliated insurgency.

Currently, Hamas and Egypt control the border in theory, but in practice Israel wields significant power over who is allowed to cross the border, said Navone.

Meanwhile, the government of Sisi has opposed purported Israeli plans to forcibly displace the Palestinians of Gaza to Egypt’s Sinai, warning of the prospect of a second Nakba, repeating the 1948 ethnic cleansing of Palestinians during the creation of Israel. A mass influx of Palestinians into Sinai therefore remains unrealised.

Faced with Israel’s relentless bombardment of northern Gaza and large parts of southern Gaza, as well as Egypt’s coordination with Israel to limit movement across the border, the Palestinian people have few options to navigate, said Navone.

“They cannot go to Egypt, and they cannot go back to the northern Gaza Strip,” he said. “Even if the war ends today, how can they go back? Gaza is almost completely destroyed and uninhabitable.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.