Silwan explained: How history and religion are exploited to displace Palestinians

The Palestinian neighbourhoods of Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan may be roughly 4km apart, lying on different sides of Jerusalem’s Old City walls, but its residents share a common struggle.

Protests against the imminent eviction of six Palestinian families from the East Jerusalem neighbourhood of Sheikh Jarrah gained global attention last month, and became the catalyst for a brutal crackdown on protests by Israeli authorities.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

A deadly escalation in violence followed, in which Israeli air strikes killed over 250 Palestinians in Gaza, including 66 children.

A further 29 were killed in the occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem, while rockets fired from Gaza killed 12 people in Israel.

After a ceasefire was announced on 21 May, activists vowed to continue raising awareness about the illegal occupation of Palestinian land, including the plight of those in Sheikh Jarrah.

Families in Silwan, another historic town south of Jerusalem’s ancient city, are also facing forced expulsions.

“The Israeli settler groups behind the eviction cases in Sheikh Jarrah are the same ones coming after these houses in Silwan,” Qutaiba Odeh, a resident whose house is threatened with a demolition order, told Middle East Eye last month.

“It’s the same shared struggle, against the same occupation,” he said. “We said save Sheikh Jarrah yesterday, we say save Silwan today.”

Carrying the spirit of that shared struggle, Palestinians took part in an awareness-raising race from Sheikh Jarrah to Silwan two weeks ago, which was heavily cracked down on by Israeli police.

Middle East Eye takes a look at the past and present of the latter neighbourhood, and how religion and archaeology are being exploited by Israeli settlers and authorities to displace its Palestinian residents.

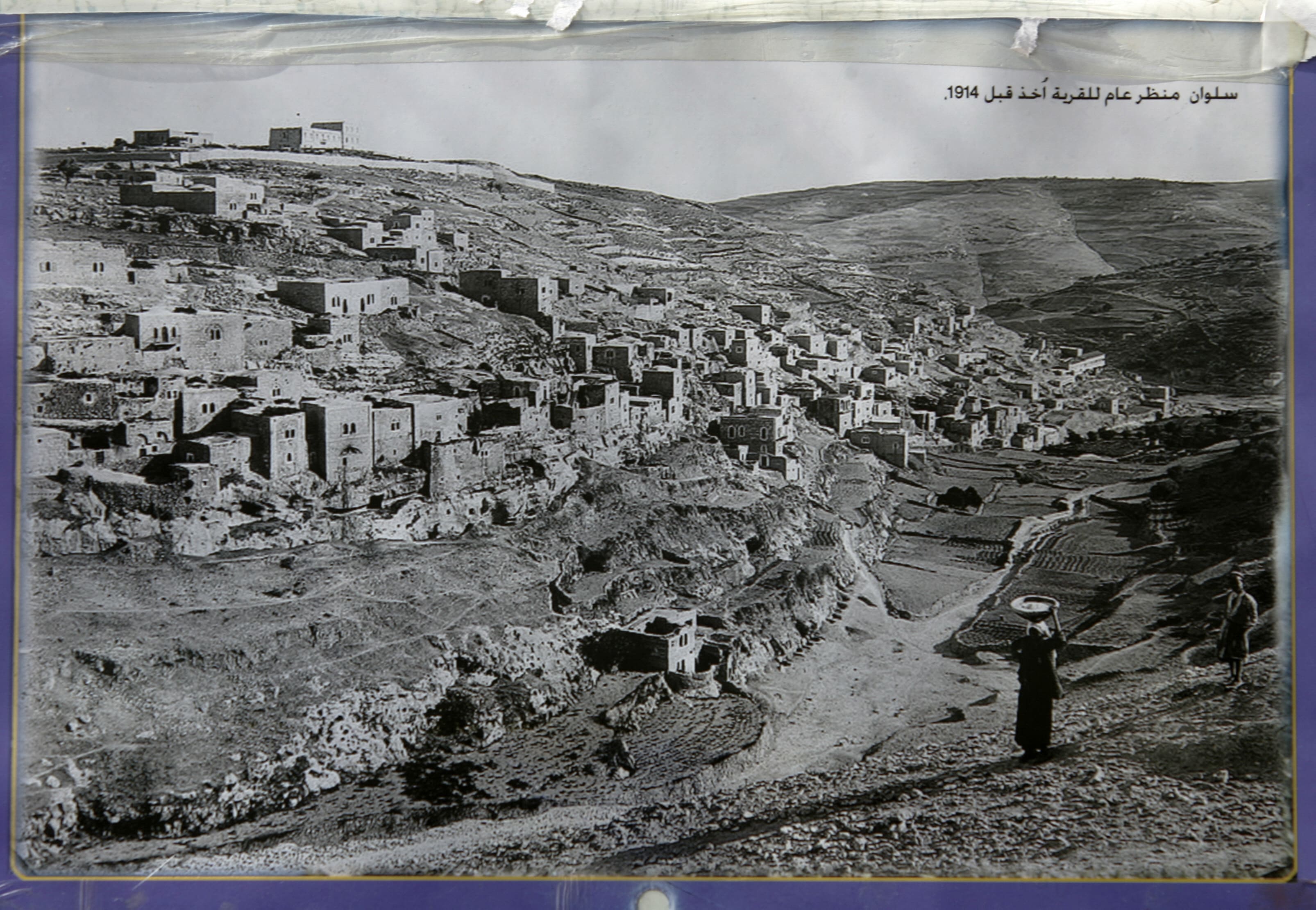

Silwan through the ages

Silwan has been continuously inhabited for over three millennia, with a varied cultural and religious history throughout.

During the Iron Age over 2,700 years ago, the Silwan necropolis was believed to be a burial place for high ranking officials from the Kingdom of Judah.

The pool of Siloam (the Greek name for Silwan), a rock-cut pool that lies in the modern-day Palestinian village of Wadi Hilweh, is thought to have been built in the same era, and rebuilt again during the Second Temple period (from the 6th to 1st century BCE).

Jesus is believed to have performed a miracle in the pool according to New Testament tradition, restoring the sight of a man who was born blind.

The modern Palestinian neighbourhood of Silwan dates back to the 7th century, when it fell into the hands of Muslim rule following the Rashidun caliphate’s conquest of Jerusalem from the Byzantine empire.

It was established as a farming village, and the second Muslim caliph Umar ibn Khattab allowed Jews to live there - among other parts of Jerusalem - for the first time after five centuries of persecution by the Romans.

The Spring of Silwan, known as Ayn Silwan, is viewed by Muslims as a sacred water source, based on Islamic hadith (sayings of the Prophet Muhammad).

Jerusalem and its surrounding areas came under the control of several different - mostly Muslim - rulers over the following centuries, most notably the Mamluks and the Ottomans.

Towards the end of the latter’s rule in 1882, a group of Yemeni Jews emigrated to Silwan amid calls from the Zionist movement for Jews from around the world to move to Palestine. The easterners were not accepted by western Jews to live in their communities, but instead invited in by the residents of Silwan, according to the educational NGO Madaa Silwan.

During the British Mandate of Palestine, a 1931 census found that Silwan had a population of 2,968, made up of 2,553 Muslims, 124 Jews and 91 Christians.

Yemeni Jews left Silwan by 1938, following turbulence during the Great Palestinian Revolt against British colonialism. They sent letters to the people of Silwan thanking them for the years they lived together.

In 1948, the town came under the administration of the Hashemite kingdom of Jordan, after the Nakba (catastrophe) in which 750,000 Palestinians were forcibly expelled from towns and cities which became the state of Israel.

Israel took full control of the neighbourhood in 1967, when it captured and occupied East Jerusalem following the Middle East war.

Since then, continuous illegal settlement activity has sought to change the demographics of Silwan, forcibly displacing Palestinian residents in favour of Jewish settlers.

Batn al-Hawa evictions

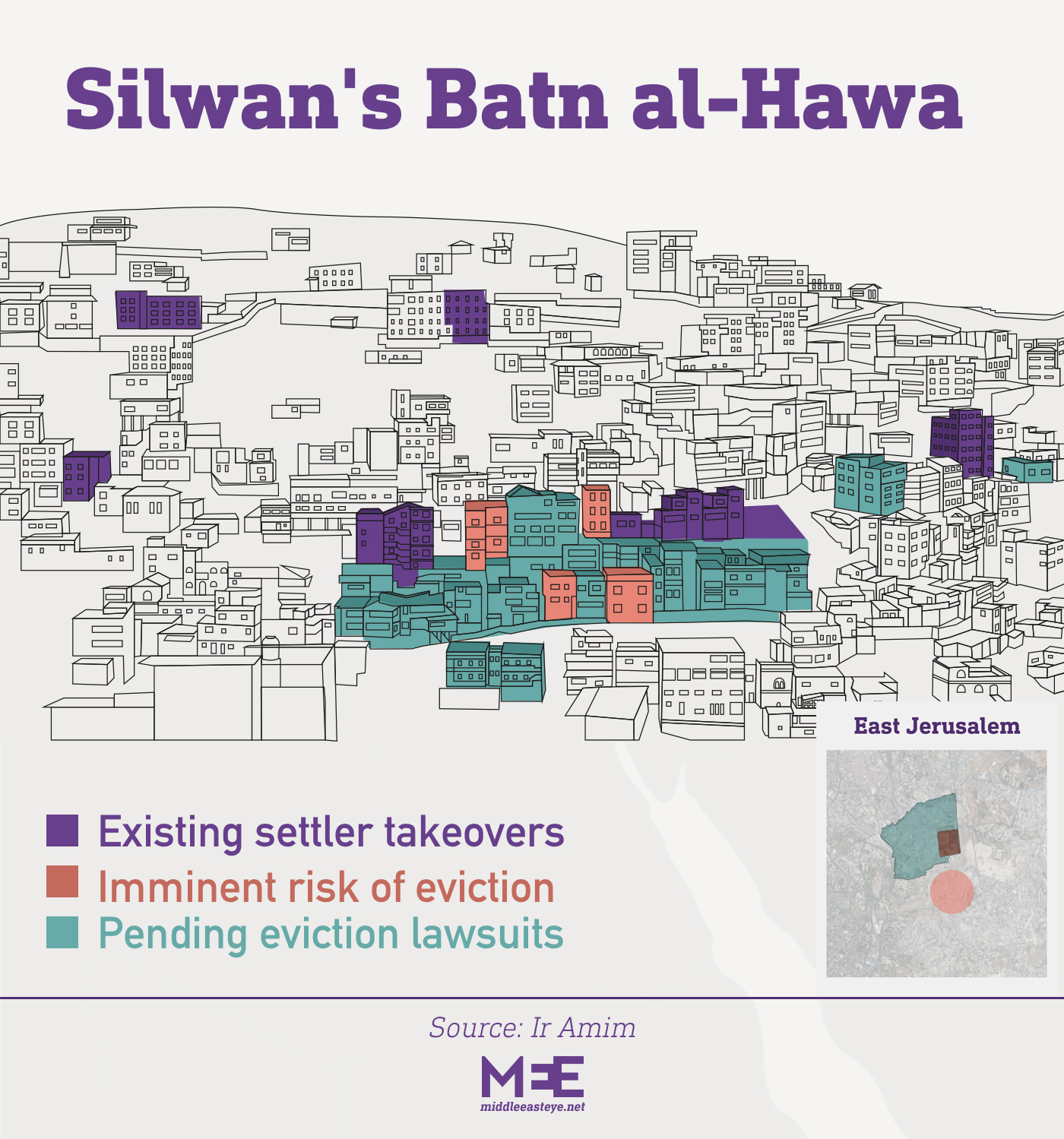

Today, the small Palestinian neighbourhood of Batn al-Hawa is one of several areas in Silwan under imminent threat.

Last month, as occurred days earlier in Sheikh Jarrah, an Israeli court postponed the decision of an appeal against the forced displacement of seven Palestinian families from Batn al-Hawa.

They included the Nasser Rajabi and Abed al-Fatah Rajabi families, who number 44 individuals in total. Some 84 families face eviction lawsuits, putting 700 Palestinians at risk of mass expulsion in the neighbourhood.

All families being forcibly evicted are in various stages of appeal proceedings. In the cases of the Duweik, Shweiki and Odeh families, the matter has reached the Supreme Court level, and the opinion of Israel’s attorney general has been sought.

Many believe the postponement of appeal verdicts in Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan are a direct consequence of media coverage, and have urged activists to continue applying international pressure.

The legal action in Batn al-Hawa was brought forward by Ateret Cohanim, one of many Israeli settler groups working with the support of the Israeli government to remove Palestinians from illegally occupied East Jerusalem and the West Bank.

The group has been suing Batn al-Hawa’s residents for nearly 20 years since it acquired the Jewish religious trust Benvenisti, which is registered as the owner of the land.

The lawsuits are on the basis that part of the neighbourhood was owned by Yemeni Jews before 1938. The action is made possible by the Legal and Administrative Matters Law of 1970, which gives Jews the exclusive right to reclaim land in East Jerusalem lost during the Nakba in 1948.

Meanwhile, the 1950 Absentee Property Law rules that the 750,000 Palestinians who were forcibly expelled during the Nakba cannot retrieve their homes.

Israeli NGO Ir Amim notes that Jews who lost their homes in East Jerusalem in 1948 were compensated with properties in West Jerusalem - and have thus been doubly recompensed by the 1970 law.

There are several outposts of settlements built in Batn al-Hawa, which initially contravened Israeli law (many have since been retroactively approved). The distinction between outposts and other settlements is not one recognised by international law, which deems all settlements in occupied territory illegal.

One of the outposts is a seven-storey building called Beit Yonatan, which was built without a permit in 2004. It was named after Jonathan Pollard, a recently-released spy who was imprisoned for 30 years in the US for passing secret American intelligence to Israel.

The settlers in Batn al-Hawa have made life increasingly difficult for Palestinians who have lived there for up to 60 years.

"Our life beside them is extremely difficult. My home lies exactly underneath one of the settler outposts. Sometimes they leak wastewater onto my house or their children throw waste, especially dirty diapers,” Kayed Rajabi, one of those who faces eviction, told MEE last year.

“They also throw stones at my children while they’re playing on the roof of the house,” he added. "All this harassment has made me more attached to this place."

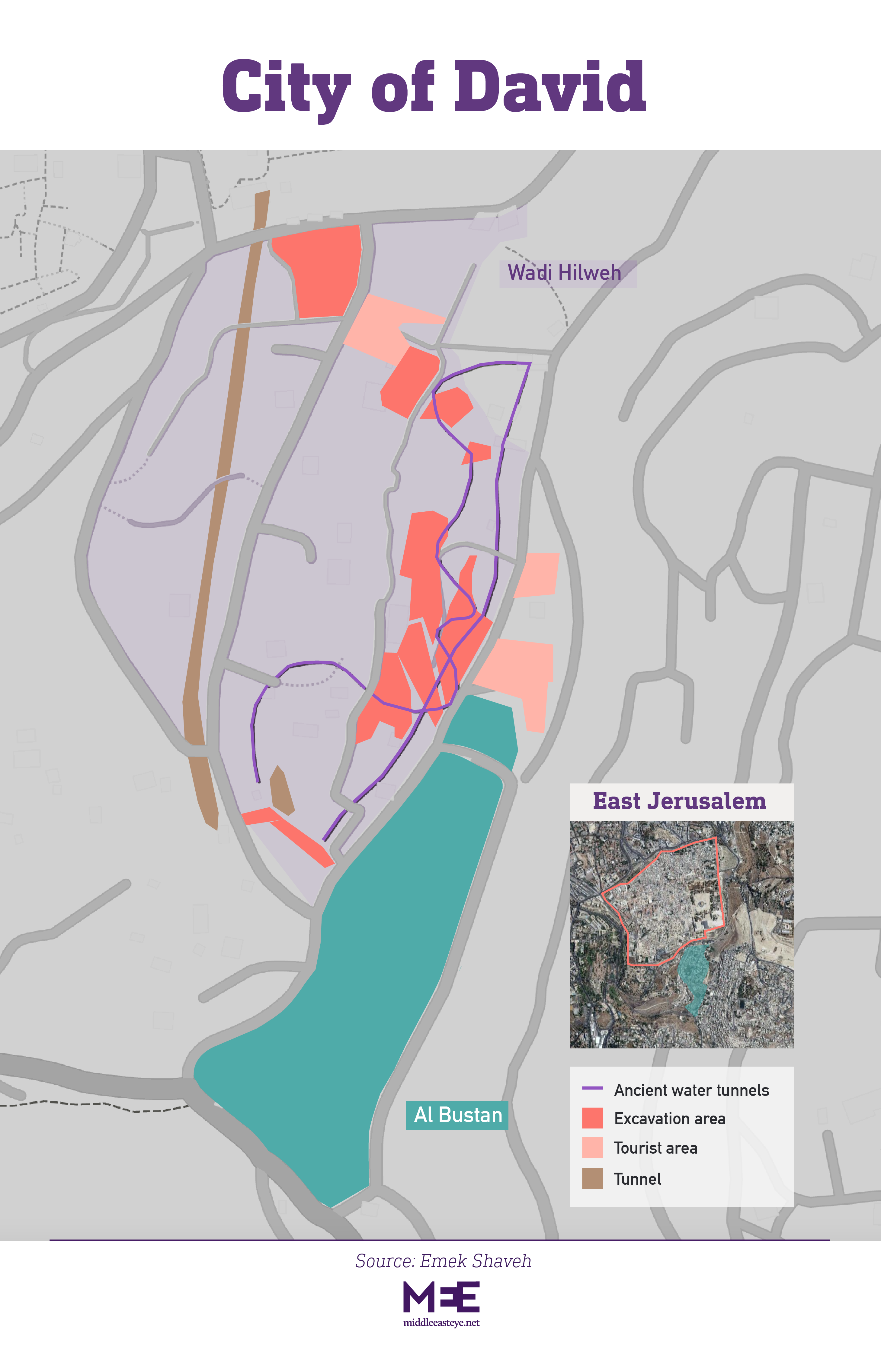

City of David project

For decades, illegal Israeli settler organisations have used archaeology and tourism as part of a deliberate ploy to justify the displacement of Palestinians in Silwan.

The settler organisation Ir David Foundation, commonly known as Elad, was set up in 1986 with the aim of using the Israeli legal system to expel Palestinians in East Jerusalem and “Judaise” the city.

Once considered an extremist organisation by Israeli politicians, Elad has now firmly established itself at the heart of the establishment. This change in fortunes coincided with a change in strategy: linking the settlements in Silwan with an ancient "lost city".

Since the late 1970s, the Israeli government has been excavating in the Palestinian neighbourhood of Wadi Hilweh in Silwan, in search of the three-millenia old "City of David". It is the supposed seat of power of King David, the biblical founding father of the Jewish nation.

The excavations are carried out by the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA), and funded by Elad. The settler organisation is also the owner of the City of David national park, which it took control of after an agreement was struck with the Israel Nature and Parks Authority in 2002.

Much of the excavation in search of ancient Jewish history is taking place underneath Palestinian homes, and have literally shaken the foundations of the people living above.

Residents of Wadi al-Hilweh have told MEE that their homes were falling apart as a result of the digging, and that many neighbours had left due to their houses collapsing.

The Sumarin family, who have lived in Silwan since the 1940s, have faced the threat of forced eviction for three decades. Elad claims that their house lies in the 3,000-year-old city.

The national park for the ancient city has been turned into a major tourist attraction, with hundreds of thousands of visitors each year.

Emek Shaveh, an Israeli NGO working against the politicisation of archaeology, has accused Elad of shaping the tour around its ideological agenda. It said that the guides focus entirely on the Judean kingdom, and ignore Jerusalem’s long and varied cultural and religious history.

Archaeologists have raised doubts over whether any of the remains found at the site are from the King David era.

An anonymous tour guide at the City of David site told MEE in 2018 that the excavation had not found one single artefact from the 3,000-year-old period. The guide, who is also an archaeologist, said that the items discovered were from more recent extinct empires, mainly Arab and Muslim, which had controlled Jerusalem over the centuries.

Emek Shaveh has also criticised the method of digging by the Elad-sponsored excavators. Rather than tunnelling vertically, the IAA has dug horizontally, against archaeological best practice. Experts have rendered information obtained from this method “worthless”.

Roman Abramovich funding displacement

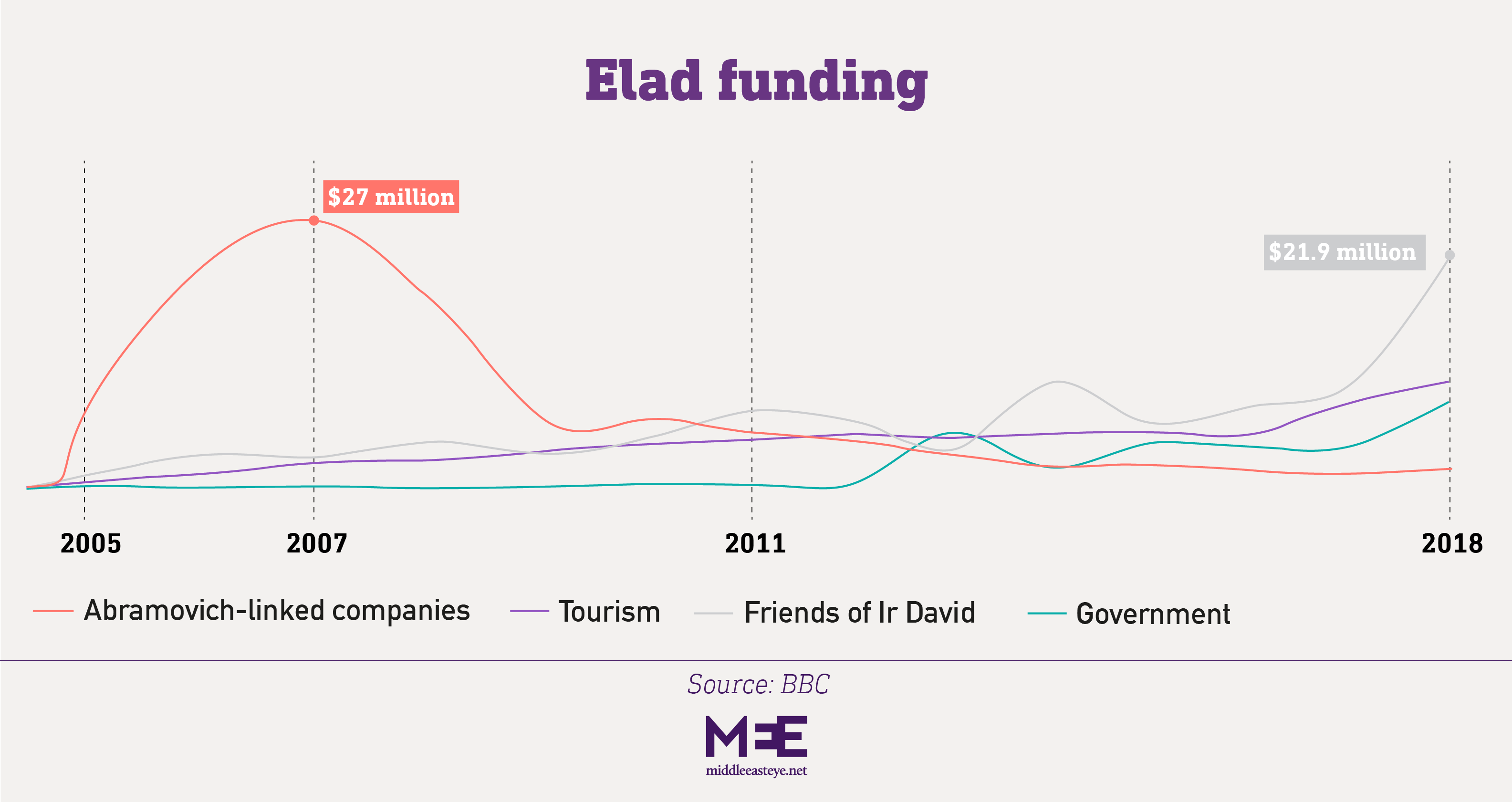

While tourism and archaeology form a bulk of Elad’s endeavours, the organisation does not hide the fact that illegal Israeli settlements are its primary focus.

“We are a foundation whose goals are to house Jewish families in the City of David,” Elad’s founder and director David Be'eri told a court last year during legal proceedings to forcibly evict an 82-year-old Palestinian man from Silwan.

“These are the foundation’s stated objectives with the Registrar of Associations for which we receive donations. This is a main part of the foundation’s goals.”

Elad’s funding has long been shrouded in secrecy, with the organisation failing for years to provide a full list of individual donors. Israeli law obligates non-profits to declare the names of those donating over 20,000 shekels, however Elad gets around this by listing the names of shell companies and front organisations.

An investigation by Haaretz in 2016 revealed details about some of Elad’s donors, which included members of the Falic family of Florida, the tycoons who own the biggest duty-free retailer in the US.

It also found that Friends of Ir David, a New York-based nonprofit, contributed 122 million shekels ($37m) over eight years. As a registered US charity, donors to Friends of Ir David were eligible for tax breaks as a result of their contributions towards an organisation displacing Palestinians.

Other donors to Elad include American businessman Roger Hertog, the late millionaire Irving Moskowitz, and Russian-American oil tycoon Eugene Shvidler.

An investigation by BBC Arabic last year revealed that the single biggest donor to Elad was billionaire Russian oligarch and Chelsea football club owner Roman Abramovich.

He controls four companies based in the British Virgin Islands - all registered on the same day in 2003 - which donated $100m over 15 years to the settler organisation.

Abramovich became an Israeli citizen in 2018, and in recent years has purchased several luxury properties in Israel. Between 2005 and 2018, half of all of Elad’s donations came from the oligarch’s companies.

The BBC Arabic report notes that towards the end of that period, Abramovich-linked funds to Elad subsided, and were eventually overtaken by Friends of Ir David and ticket sales from the City of David tourist site.

‘Judaisation’ of East Jerusalem

In addition to Wadi Hilweh, archaeology and tourism are also being used to displace Palestinians in the al-Bustan neighbourhood of Silwan.

Israeli authorities are going ahead with plans to demolish 100 properties, home to over 1,500 Palestinians, in order to build another “biblical” park.

Fakhri Abu Diab, member of the Defense of Silwan Land Committee, warned on Monday that 17 homes belonging to Palestinian families in al-Bustan will be demolished by the end of next month by Israeli authorities.

Families were given 21 days to evacuate and demolish their houses themselves, or face demolition costs from the municipality.

The Gan Hamelech (King’s Garden) in al-Bustan is purported to have been a royal garden used by ancient Israelite rulers, and will soon become a new tourist attraction.

Israeli demolitions of Palestinian houses in al-Bustan have been justified on the grounds of residents not having a building permit. However, the Israeli government makes it virtually impossible for Palestinians to get those permits, while announcing and expanding settlements in East Jerusalem and the West Bank regularly.

Alongside the proposed garden, Israeli authorities announced in November plans for excavation works in Silwan to prepare for the construction of a cable car running from the Old City's Dung Gate (or Silwan Gate) to West Jerusalem.

The controversial project would dramatically alter the historic Old City and expand the Israeli presence in Palestinian-majority neighbourhoods. It has been branded a “racist” plan which would blight the historic panorama of Jerusalem.

Elsewhere in Silwan, residents of the Wadi al-Rababa neighbourhood have faced continued harassment and attacks by Israeli forces and settlers.

In early 2018, the Israeli authorities dug the foundations for a suspension bridge, expected to be 240 metres long and 30 metres high, which would run from the al-Thawri neighbourhood, passing through Palestinian-owned lands in Wadi al-Rababa, and reaching the Muslim endowment area of al-Dajani.

The bridge was part of a "Judaisation" project funded by the Israel Land Authority and the Open Spaces Fund at the cost of six million shekels ($1.9m), which plans to establish Talmudic gardens and Israeli tourist parks which link the Old City with Wadi al-Rababa.

Israel’s grand strategy of building settler units and a string of parks themed after biblical places and figures around the Old City of Jerusalem has been dubbed the "Holy Basin”.

These coordinated and calculated efforts to "Judaise" East Jerusalem at the expense of Palestinians continue unconstrained, despite being in clear contravention of international law.

Time will tell if the momentary halt in legal action against families in Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan brought about by recent international pressure will sustain longer term.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.