What happened to Israel’s Labor party?

In August 1969 - two years after the 1967 war - Israel held a general election. Freshly elected Prime Minister Golda Meir led the Labor party, in an alliance with the more left-leaning Mapam, to a crushing victory, winning 56 of 120 seats in Israel’s parliament, the Knesset.

Fifty years later, Labor is down to three seats - and that number may drop down to two, as one MP, Merav Michaeli, has threatened action in response to the party’s decision on Sunday to join the ruling coalition led by rightwing Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Labor’s fall from grace has been so dramatic that many Israeli political commentators, as well as many party veterans, say the party, once central to the history of Zionism, is no more.

"The Labor party, as a political body with some influence, has disappeared," former minister and MK Uzi Baram told Israeli news site Local Call.

How did "the party that founded Israel", as it is commonly referred to in the Israeli press, the political heir of Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, find itself on the path towards extinction?

A slow decline

The process leading to Labor’s ongoing demise took root before the party was even born.

In the 1950s, the mainly Ashkenazi - Jews of European origins - establishment of Ben-Gurion’s Mapai party mistreated Jews from the Arab world who were immigrating to the newly established Israel.

Mapai overwhelmingly looked down on these Mizrahi Jews, rejecting their "Arabic" culture, pushing them to work in manual labour and live in makeshift slums outside big cities, or in far-away small towns and villages built in order to "secure" Israel's boundaries.

When the second generation of Mizrahi immigrants politically came of age in the early 1970s, the community became more outspoken about their resentment over such discrimination.

As a result, they steered away from the Labor party - which was created in 1968 when Mapai merged with several other left-leaning parties - and embraced its political opponents further to the right.

The 1973 Arab-Israeli war further cemented that shift. Carried away by Israel’s victory in 1967, Golda Meir did not believe that war was imminent. She was confident that Arab states would not dare attack Israel, fearing an inevitable defeat.

But the 1973 conflict, also known as the Yom Kippur War, saw the Israeli army lose important battles for the first time since 1948, costing the lives of more than 2,500 Israeli soldiers. The conflict shattered many Israelis’ confidence in their government and the political movement which had led Israel since its inception, now represented by Labor.

The combination of a new Mizrahi generation and general anger over the 1973 debacle led Labor to experience its first electoral defeat in 1977, from which it would never really recover.

Labor still enjoyed substantial support, thanks to its grip on the largest workers' union in Israel. Histadrut was much more than a union - the organisation provided cheap healthcare and owned factories, banks and insurance companies, making it at one point one of the country’s biggest employers.

But Labor became the party of the upper-middle class, slowly distancing itself from its old social democratic and socialist slogans, eventually cutting ties with Histadrut in 1994.

After losing its unionist and social democratic base, Labor was left with one main pillar: leading the Israeli "peace camp" seeking a negotiated resolution with the Palestinian leadership.

Building on this platform, Labor was able to return to power in 1992 with Yitzhak Rabin at the helm. Under Rabin, Israel signed the Oslo Accords - its first and so far only agreement with representatives of the Palestinian people.

Despite Rabin's assassination in 1995 at the hands of an Israeli ultranationalist, Labor was nonetheless able to return to power in 1999 with the promise of reaching a definitive peace deal with Palestinians.

But Labor leader and then-Prime Minister Ehud Barak scuppered the party’s diplomatic platform when he declared, following the collapse of the Camp David talks in July 2000, that "there is no Palestinian partner" for peace.

The Second Intifada broke out a few months later, effectively taking with it Labor’s last pillar in Israeli society.

Since 2000, Labor has never regained power, winning fewer than 20 seats in most elections since. Its middle- and upper-middle-class voters moved on to centrist and neoliberal parties like Ariel Sharon's Kadima (Forward) and, later on, to Yair Lapid's Yesh Atid (We have a future).

The rise of the Blue and White party in 2019, led by former army generals whose main promise was to return Israel to "normality" and save it from Netanyahu's attacks on the country’s institutions - mainly the judiciary and the army - dealt a final blow against Labor.

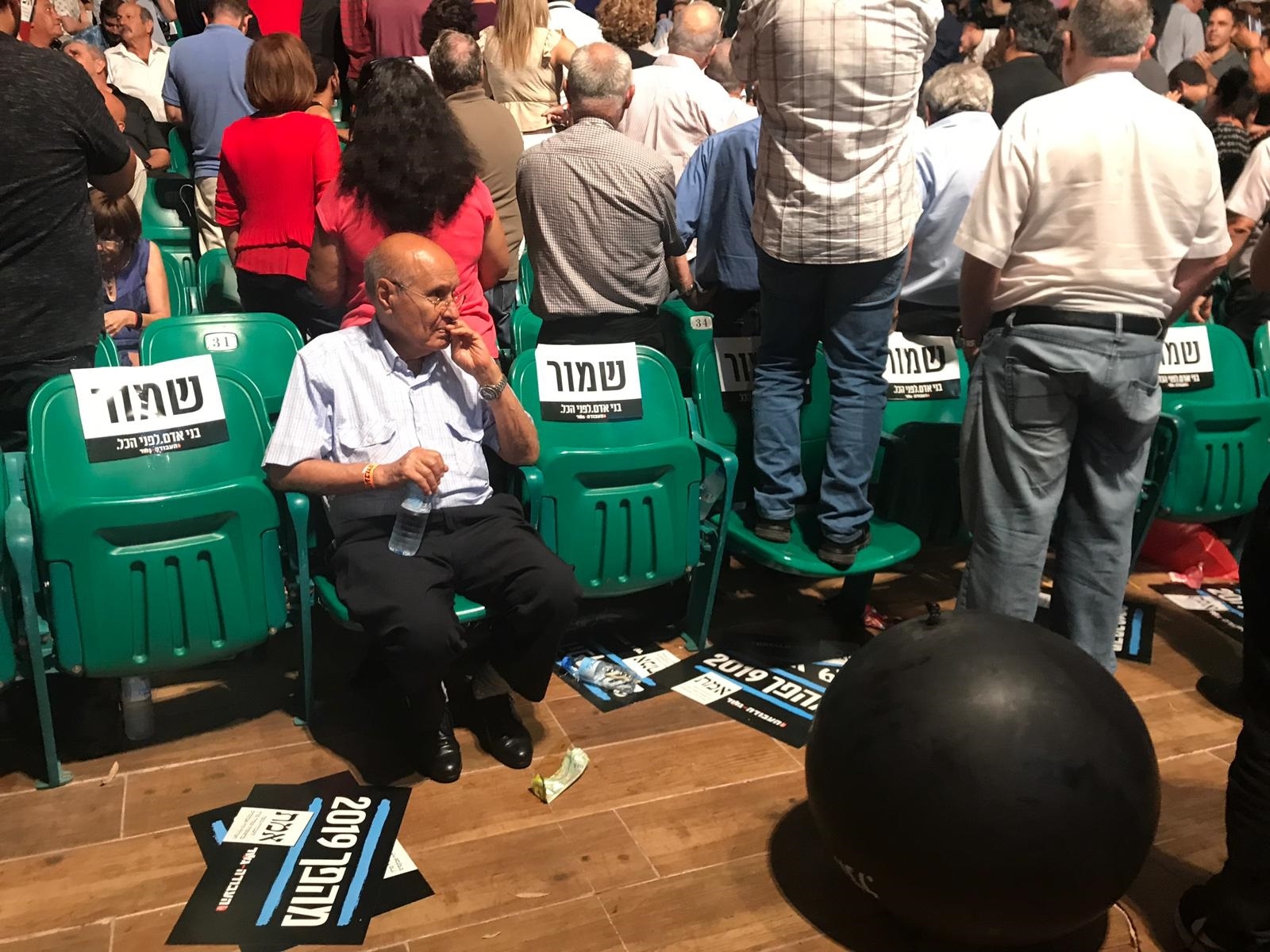

As Israel has undergone three legislative elections in the span of a year, and as Netanyahu and Blue and White’s Benny Gantz battled it out for a clear majority, Labor saw its number of seats dwindle from six in the April 2019 vote down to three in March.

After its decision to join Netanyahu's government earlier this week, what is left of Labor is expected to merge with Gantz's centrist Blue and White. In the current context, doubts loom large over whether Labor will run independently in any coming elections.

What left is left for Israel?

For more radical Jewish-Israeli leftists and for many political activists within Israel’s Palestinian community, Labor’s downfall does not come as such terrible news.

In effect, it is hard for Palestinians to mourn the end of the party directly responsible for the Nakba, which led to the displacement of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians in 1948.

It is perhaps only fitting that the very party that implemented the Absentee Property law, expropriating countless Palestinians and paving the way for settlements on occupied Palestinian territory after 1967, is now joining a government that has officially put annexation on its agenda.

Casting aside more distant history, Labor has been perceived by many as an obstacle to the creation of a more genuine and progressive left in Israel.

Its neoliberal positions on many issues, its contempt towards Mizrahi Jews and their culture, its almost systematic support of Israeli military operations and its refusal to see Palestinian citizens of Israel as equal political partners - aside from during Rabin’s brief time in power - has led many to believe that there is little hope for real change in Israel as long as this political dinosaur remains.

But now that the dinosaur has turned into a kitten, prospects for Israel’s centre-left remain bleak.

For three elections, Blue and White managed to prevent Netanyahu from being re-elected, even obtaining enough MPs to be tasked with forming a government by cobbling together a strange coalition spanning from the Joint List - representing Palestinian citizens of Israel - to the openly anti-Palestinian Yisrael Beiteinu party.

But the coalition split after Gantz signed a deal with Netanyahu earlier this month to form a unity government. After a year during which Gantz had positioned himself as Israel’s most viable alternative to Netanyahu and his Likud party, his about-face has ignited animosity from his former coalition partners, making cooperation among them unlikely in the near future.

With Labor at its lowest point, Meretz - the descendent of the Mapam party - has also been badly hit and has lost its confidence as it too garnered only three seats in the latest election.

The only stable force remaining on the Israeli left is the Joint List. Despite the setback it experienced after agreeing to join forces with Gantz - only to see him abandon them without a second thought - it appears that Palestinian voters continue to stand by the political coalition.

Support for the Joint List among Jewish voters is also on the rise, as Joint List leader Ayman Odeh has been warmly welcomed at demonstrations held by centre-left Jewish activists vehemently opposing Gantz's "surrender" to Netanyahu.

Yet the Joint List is and will remain a predominantly Palestinian political force in the foreseeable future. Therefore, Israel’s progressive left remains faced with the crucial political challenge of forming some kind of a wide-ranging popular political coalition comprising both Jewish and Palestinian forces inside Israel.

For many reasons, this is a tall order, as many gaps need to be bridged. For example, the definition of Israel as a "Jewish and democratic state" is a given for many Jewish Israelis, even on the left; while for Palestinian citizens of Israel, such a statement is a non-starter.

But from the moment he entered national politics in 2015, Odeh has often repeated that the Palestinian community in Israel is “not able do to it alone, yet without us, it isn’t possible".

It remains to be seen whether the collapse of the Labor party, the historical leader of the Jewish centre-left, will become an opportunity for the emergence of a real progressive left in Israel.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.