Jordan: Is the UN’s biometric registration for Syrian refugees a threat to their privacy?

Nearly nine years ago, Azzam placed his head before a compact, black box at the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) office in Amman, struggling to hold his eyes open as the machine blinked. He was exhausted.

Months before arriving at the office, Azzam had joined a protest in Homs, Syria and was jailed for three torturous months before fleeing to Jordan. Azzam hoped the hi-tech machine, which captured his iris scan and registered him as a refugee, would be his portal to a better life.

'I know that I’m wanted by the regime, but I registered with UNHCR to get food'

- Azzam, Syrian refugee in Jordan

“I know that I’m wanted by the regime, but I registered with UNHCR to get food,” said Azzam, sitting on the ground of his Amman apartment, his infant daughter napping between his arms. “They took my iris scan, but I didn’t get any clarification about how it would be used or protected.”

Governments and humanitarian organisations began databasing huge amounts of biometric information on Syrian refugees as they fled the war. Often a precondition to entering a new country and receiving humanitarian aid, biometric data helped UNHCR make massive gains in registering refugees, cutting the waiting time from eight months to zero in Jordan.

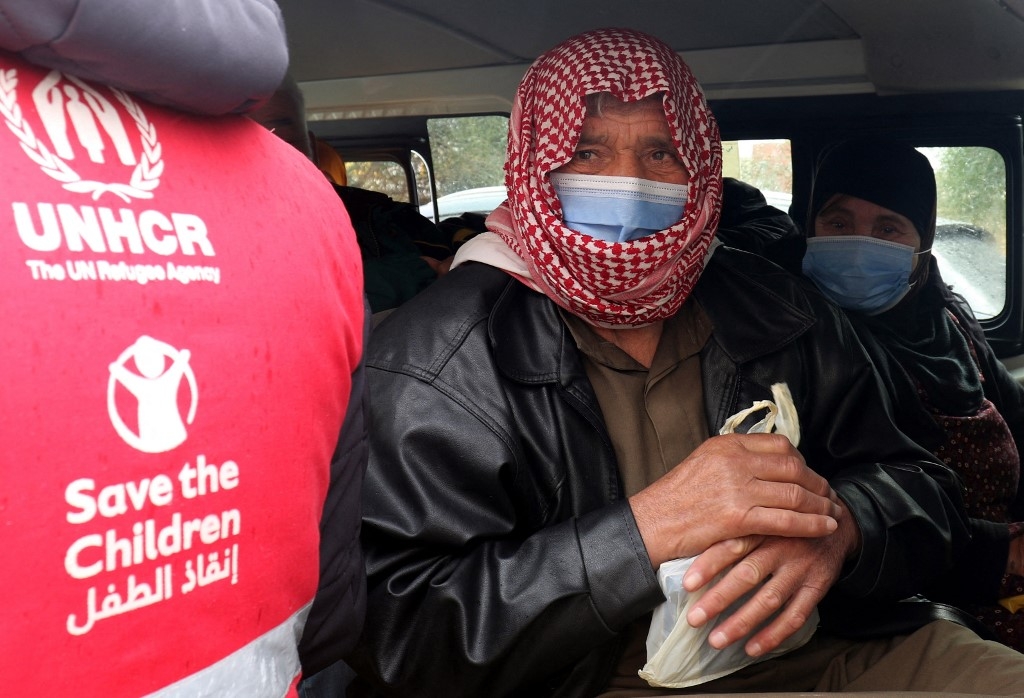

Covid-19 pushed humanitarian organisations to further increase their use of biometrics, which can be contactless. But even as biometrics expands, human rights researchers are concerned about the risks to refugees like Azzam.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

“Our concern comes from the fact that these kinds of activities are happening in countries that have no data protection laws in place, for the most part,” Belkis Wille, senior researcher with the Conflict and Crisis division at Human Rights Watch, told Middle East Eye. “Humanitarian organisations don't feel that they're bound by any data protection principles beyond what their own policies have outlined.”

How are biometrics used?

UNHCR has been using biometrics since the early 2000s to track refugees from Burundi to Malaysia, though UNHCR in Jordan was the first operation to use iris-scanning to register refugees and distribute assistance.

The refugee agency collects iris scans of Syrian refugees in Jordan and Lebanon using the British-Jordanian company IrisGuard's system. Looking at the IrisGuard machine, refugees can pay for groceries or withdraw cash at enabled ATM machines through the UN’s partnerships with Cairo Amman Bank, LibanPost and other private companies.

'We started to use the iris scan because it’s more hygienic'

- Dima, charity worker in Jordan

The humanitarian sector had long used photographs to identify refugees, but biometrics, like fingerprints and iris scans, are faster and more accurate.

UNHCR now owns one of the largest multinational biometric databases in the world, holding the data of millions of adults and children over five. It uses biometrics for identification, comparing an individual’s biometric profile against a database to prevent refugees from registering twice and doubling their receipt of aid. “If a refugee moved from Jordan to Egypt, we can know that this is the same person,” said then-UNHCR representative to Jordan Andrew Harper in 2014.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, biometrics gained a greater foothold. In Jordan, Cairo Amman used mobile bank buses with iris recognition to help refugees withdraw humanitarian aid, while WFP used mobile iris-scanning devices in delivering food to refugees. Several NGOs also switched to using ATMs with iris scans to limit contact between refugees and staff.

“We started to use the iris scan because it’s more hygienic,” said Dima, who works at a large international NGO in Jordan that began using eye scan-equipped technology to distribute cash to refugees. “Covid-19 is the main reason we switched,” she told MEE. Her organisation has no plans to switch back, even as the pandemic ends.

Absence of informed consent

Since UNHCR began using biometrics, international consent and data protection norms have changed.

“Issues like the right to consent and the right to be forgotten, that feature in modern legislation like the GDPR or the California Law, are rather recent. These legacy systems were created with different assumptions,” former UNHCR official Karl Steinaker told MEE. “Privacy was never a core element of design.”

Although UNHCR states that submitting biometric data isn’t mandatory, exceptions are rare, despite evidence that Syrian refugees aim to avoid submitting their biometric data in other contexts.

An informal survey of 10 Syrian refugees living in Amman conducted for Middle East Eye found none recalled providing consent or learning how their iris scan would be used. This aligns with a previous study in Amman which found that most Syrian refugees were unsure about the purpose of their iris scans and who could access their data.

These findings are understandable given UNHCR lacked a publicly available data protection policy until 2015, years after many refugees had provided their data.

Even today, UNHCR’s data protection procedures are rife with ambiguities. In one example, the refugee organisation released a handout for refugees which stated, “Biometric data is not shared with any third party.” However, the official data protection policy states that it may transfer personal data, including biometrics, with “national governments, international governmental or nongovernmental organisations, private sector entities or individuals”.

A spokesperson for the agency told MEE: "Before obtaining any personal data, UNHCR informs refugees in person and through information pages and other means of communication how the data may be used. Biometric data of refugees and asylum-seekers is not shared with the government of Jordan."

The spokesperson insisted "UNHCR will only share or provide access to data where there is a legitimate basis and specific purpose in pursuance of its protection and solutions mandate."

Nefarious uses of biometrics are mounting. In Afghanistan, the US government, UN agencies and the World Bank helped build systems to hold biometrics on Afghans, often for humanitarian work. The Taliban, since its takeover of Afghanistan last summer, has gained access to biometric devices that were left behind by US forces, placing activists, LGBTQ+ Afghans, American allies and others at risk.

UNHCR also collected biometrics on Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh who were fleeing genocide in Myanmar. Although previously undisclosed to refugees, the UNHCR was sharing this data with Bangladesh, even as the Bangladeshi government negotiated with Myanmar to repatriate the refugees.

Do host governments collect biometrics?

Governments hosting refugees have also aimed to gather biometric data.

Turkey collected fingerprints and palm-vein prints on over a million Syrian refugees, among the first entrants in its National Biometric Fingerprint System. In 2016, Turkey passed its Personal Data Protection Law, which is based on the GDPR and prevents organisations like UNHCR from collecting biometric data on refugees in Turkey and processing it on overseas servers.

'Jordanian authorities are collecting [biometrics] in UNHCR-run camps'

- Belkis Wille, HRW

In contrast to Turkey, the UNHCR has provided authorities in Lebanon and Jordan with equipment and training on biometrics. UNHCR and the governments of Lebanon and Jordan use the same manufacturer, IrisGuard, to collect the data.

The UNHCR operates at the pleasure of the host governments, so maintaining a positive relationship is essential.

“The Jordanian authorities are collecting it [biometrics] in UNHCR-run camps, in a structure that has been set up by UNHCR,” Wille told Middle East Eye. “There’s a question about the role of UNHCR essentially facilitating that data collection.”

In Lebanon, officials have been in a battle with UNHCR to gain access to its database, even despite UNHCR’s provision of biometrics equipment to its government. In 2014, then Social Affairs Minister Rashid Derbas said the government “was working with UNHCR to establish a system that would turn the data over… Why wouldn’t they [UNHCR] give it to us? They are working on Lebanese territory.”

UNHCR staff denied that iris scans were being shared with Lebanon’s increasingly pro-Assad government.

Refugees often provided their biometric data to get food and money.

While informed consent is a core component of most data protection regulations, fleeing refugees may be incapable of freely consenting when the provision of personal data is required for their next meal. UNHCR can then keep their data indefinitely, even after assistance stops.

"I used to be afraid of getting taken back to the Assad regime’s prison,” said Azzam, holding his daughter’s hand in their Amman neighbourhood, where prices have soared. “Now, I get no assistance. All I think about is providing for my family.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.