Suicide exposes the ongoing trauma of Iraq's Halabja killings

The picture shows a man, his face wrapped in scarves. He is lying on the ground next to a wall, a baby in his arms. It was 20 March 1988 and Saddam Hussein's forces had launched a chemical weapons attack on the town of Halabja, in northern Iraq.

Omar Khawar was a Kurdish father trying to save his son. Instead, they both died, and the image shook the world.

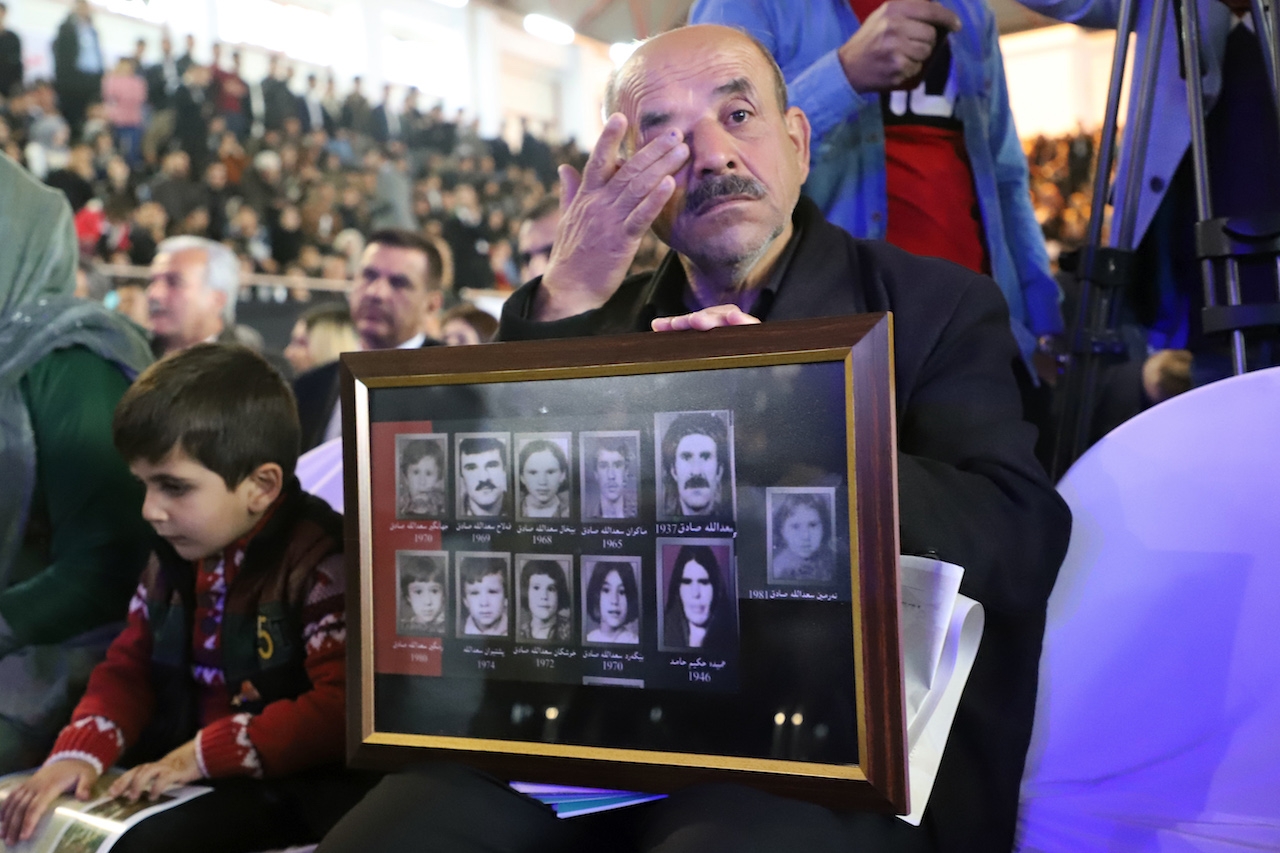

The attack on Halabja, which cost around 5,000 lives, was the single worst incident in the Iraqi government's wider Anfal campaign, which targeted Iraq's Kurdish region between 1986 and 1989, killing as many as 182,000 people.

It left thousands of survivors with long-term psychological and health conditions.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Last Sunday, the body of 39-year-old Kawa Salih, a survivor of the 1988 massacre, was found in Halabja park. He had hanged himself from a statue.

According to a relative speaking to the local NRT news outlet, he had been suffering from chronic health problems.

In a note left by Salih, he said he lived in "grief and pain" and attacked the ruling political class in the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG).

"I have only one regret - I couldn't see your humiliation and end," he wrote.

Salih's death has brought to attention the failure of the KRG, the autonomous administration in northern Iraq set up after the fall of Saddam Hussein, to provide physical and psychological help for the thousands of survivors of the 1988 attack.

Speaking to NRT, the head of Halabja's Martyrs and Anfal Victims General Directorate said that each year several survivors of the attack take their own lives, often because they had trouble coping with chronic health problems.

'There are really limited human resources, there are only a handful of psychotherapists. So we cannot offer psychological support for the whole city, we can't do this, it's impossible for us'

- Ibrahim Hama Saeed Mohammed, psychotherapist

Currently, there is only one organisation in the city of Halabja that exists to provide mental health treatment for survivors of the massacre, the Jiyan Foundation, an NGO created in 2005 that helps the all too many survivors of various traumas in northern Iraq.

Ibrahim Hama Saeed Mohammed is a psychotherapist for the Jiyan Foundation in Halabja specialising in trauma therapy. He is also, along with his family, a survivor of the 1988 massacre himself.

He told Middle East Eye that the foundation saw around 2,000 patients regularly and struggled to provide the kind of support that was needed to cope with an issue that has lingered for more than 30 years.

"There are really limited human resources, there are only a handful of psychotherapists. So we cannot offer psychological support for the whole city, we can't do this, it's impossible for us," he said.

The primary problems facing survivors of the massacre are anxiety and depression, but also post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The psychotherapist said that there was a lack of awareness of mental illness, particularly among older people, who were often more likely to go to religious leaders if they had problems.

Another major problem, he added, was trans-generational trauma, in which parents apparently passed on aspects of their trauma to their children.

"For example, now I have a patient with PTSD, and once I invited her daughter. She wasn't even born at [the time of the massacre] and yet she was able to narrate the events so clearly she cried several times. So this is what happens here," Saeed Mohammed said.

'The government doesn't care at all'

The Halabja massacre has become an event of intense historical importance for Kurds, both in Iraq and internationally, and the KRG has sought to assist survivors through policies and by setting up institutions to aid them.

A specific institution, the Ministry of Martyrs and Anfal Affairs, exists to provide, in its own words, "material and moral care" to survivors of the 1988 killings, as well to the families of those who died fighting in the line of service up to the present day.

The government also provides monthly salaries for the survivors and has constructed houses for them.

But many thousands of people have health needs that are not being provided for, and Saeed Mohammed said there was no funding forthcoming to deal with these lingering problems.

"The government doesn't care at all," he said.

"Many people have terminal diseases, eye disease, skin disease, respiratory disease, but there are no specialist places or people trained here to deal with them."

He said his own mother suffered from a number of these problems.

"I'm a survivor, I and my family are survivors, so I can understand them, I know what the problems are," he said.

"The government doesn't support us. It doesn't support affected people."

A study carried out in 2018 that interviewed a cross-section of Halabja survivors found that all those interviewed had "no, or only poor, access to healthcare services and limited access to specialist care".

It also found that "all reported [a] lack of financial resources to obtain treatment".

In 2019, the KRG did open what it called a "special hospital" for the purpose of helping survivors of the massacre.

But Saeed Mohammed dismissed this, saying that in practice there was no difference between that hospital and others in terms of the specialist care needed, an issue that has also been raised by the Anfal ministry.

He said gestures like this, as well as the highly publicised 30th anniversary commemorations in 2018, were largely just for show.

"They are doing this just for the media. To attract the attention of European countries. It's not practical things, it's just speech," he said.

"It's worth nothing for the affected survivors."

Not the last genocide

The 1988 killings were far from the last massacres carried out in Iraq, nor even the most recent classified as a "genocide".

In 2014, the Islamic State (IS) group swept across northern Iraq, capturing much of the country.

One of its most brutal acts was the mass killing of as many as 5,000 Kurdish Yazidis in the province of Sinjar, less than 400km from Halabja.

The act, which the UN later deemed a genocide, resonated across the Kurdish region, drawing horrific parallels for many.

Kamal Chomani, a Kurdish political analyst and non-resident fellow at the Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy, said a major factor in the continued collective trauma of the Halabja survivors was the failure to hold to account those complicit in the attack or pursue the international actors involved in supplying the chemicals used.

"The catastrophic problems of the KRG and Iraq have led Iraqis and the international community to almost forget about the massacres [Saddam Hussein's] regime did against the Kurds," he said.

"If Iraq, the KRG and international community had understood the impacts of the Anfal and Halabja massacres, the Islamic State group might have not been able to massacre the Yazidis and other Iraqis."

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.