'No friends but the mountains': History repeats itself with latest US betrayal of Kurds

A popular saying goes that Kurds have "no friends but the mountains".

Since the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, when the first hints of independence were dangled in front of them by imperial powers, Kurdish nationalist groups have regularly entered into alliances with powerful nation-states only to later be abandoned when those countries' short-term interests have been fulfilled.

The cycle of promise and let-downs has been ongoing for a century, and with the exception of the establishment of the autonomous Kurdish Regional Government in northern Iraq, has continued to see Kurdish national, political and cultural ambitions thwarted.

The decision on Monday by US President Donald Trump to withdraw American troops from northern Syria in anticipation of a Turkish invasion is only the latest in a long line of betrayals.

Treaty of Sevres; Treaty of Lausanne

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Following the end of World War 1, the allied powers occupied Anatolia and began the process of carving up the crumbling Ottoman Empire among themselves and their allies. The Treaty of Sevres, signed in 1920 - including by a puppet Ottoman government in Istanbul - would have seen part of Anatolia ceded for the creation of an independent Kurdistan, including the city of Diyarbakir that lies in modern Turkey's southeast.

However, the treaty enraged Turkish nationalists who soon launched the Turkish War of Independence. Led by war hero Mustafa Kemal Pasha (later known as Kemal Ataturk), Turkish nationalist forces seized control of Anatolia and the Treaty of Sevres was never implemented. It was instead supplanted by the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923.

The second treaty set the current boundaries of the Republic of Turkey - apart from the disputed areas of Mosul and Hatay - and the word "Kurdistan" would soon be stricken from Turkish textbooks despite it having been an acknowledged region of the Ottoman Empire.

The two treaties have long stood as a symbol of national tragedy for Kurdish nationalists in a similar fashion to the Balfour Declaration for Palestinians, which eventually led to the establishment of the state of Israel on Palestinian land.

Second Iraqi-Kurdish War

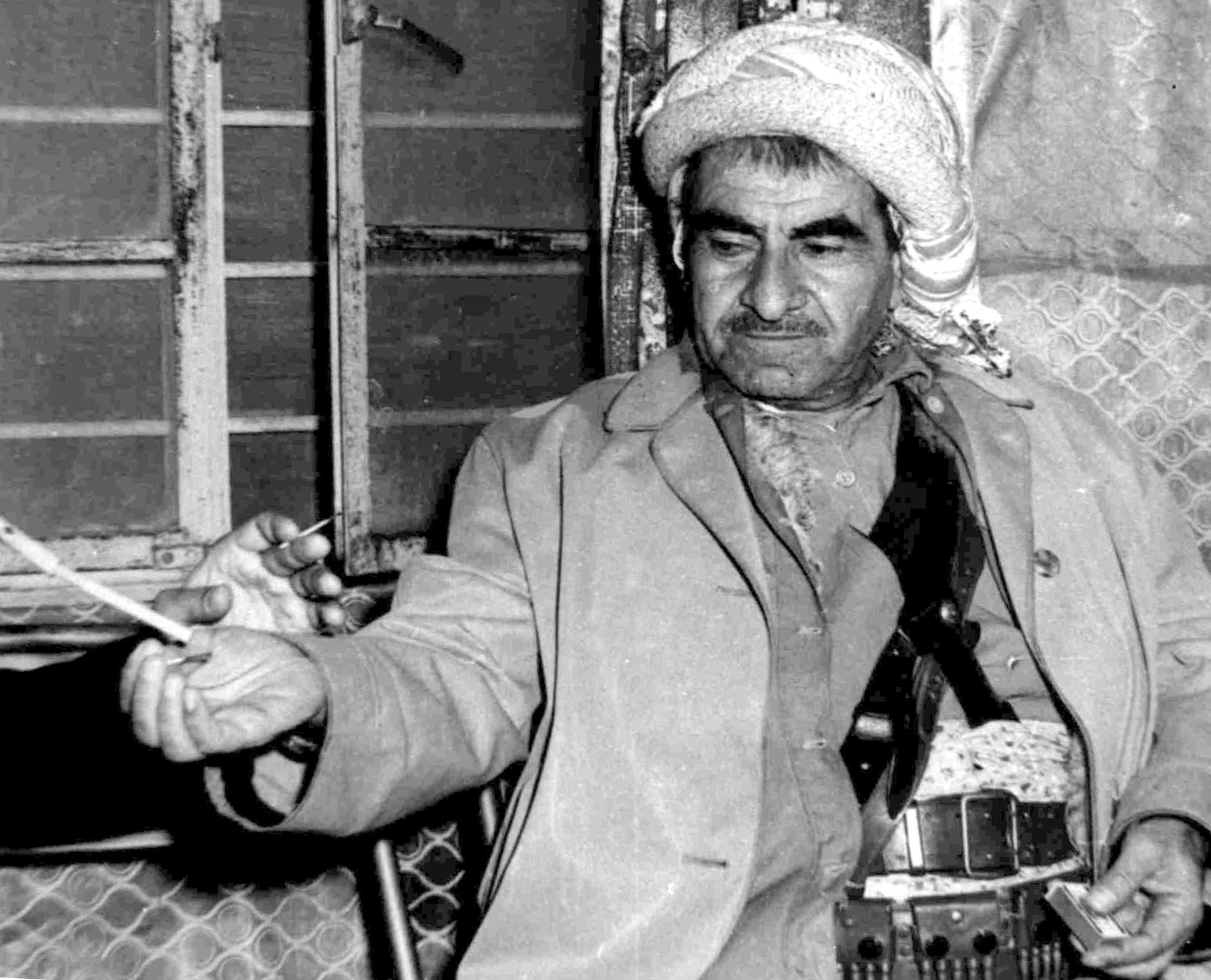

In April 1974, Mustafa Barzani - leader of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and father of former president of Iraq's Kurdistan region Massoud Barzani - once again attempted to launch an armed struggle for Kurdish autonomy in northern Iraq.

Both Iran and Israel, who were then allies with a mutual interest in undermining the Baathist-controlled government in Iraq, provided material support to the Iraqi Kurds in their fight, as they had done in the first Iraqi-Kurdish war between 1961 and 1970. Iran, in particular, wanted to wrestle territorial concessions from Iraq.

In 1975, after Baghdad made territorial concessions to Iran, the latter abruptly withdrew its support for the Kurds - along with Israel, who funnelled their support through Iran - and Iraq swiftly crushed the rebellion.

The defeat of the conservative, tribalist KDP was highly scarring for Kurdish nationalists and is cited by some as the impetus for the creation of the overtly left-wing Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) in 1978.

1991 uprisings

A rare example of a longterm success story for the Kurds, the 1991 uprisings that swept Iraq after the disastrous Gulf War saw the first steps for Iraqi Kurds towards the creation of an autonomous Kurdish region.

The uprisings against former President Saddam Hussein's autocratic rule were brutally crushed in the south of the country, with thousands killed in retribution. Kurds had suffered a genocide under the Baath regime, known as the Anfal campaign.

In 1991, however, the US imposed a no-fly zone which allowed the KDP and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) to maintain control of the Kurdistan region and create a de facto autonomous administration. In 2005, after the overthrow of Saddam Hussein by a US-led coalition, that autonomy was written into law, leading to the creation of the Kurdistan Regional Government.

US support for Kurdish groups during the uprising marked the beginning of a formal alliance between the Americans and the Iraqi Kurds that has largely continued to this day; an alliance apparently considerably more stable than the one formed with the Syrian Kurds, not least due to the KRG's good relations with Turkey.

Expulsion of Ocalan from Syria

In 1979, shortly after the establishment of the PKK, leader Abdullah Ocalan moved to Syria, which would become his primary base of operations for the next 19 years.

The late Syrian President Hafez al-Assad had long regarded the PKK and Ocalan as a useful tool to use against rival Turkey, with whom there were numerous disputes over land and resources, as well as being on largely opposite sides during the Cold War.

In 1998, however, the presence of Ocalan in Syria and ongoing PKK attacks eventually became too much for Turkey and it threatened an invasion of Syria if the Kurdish leader wasn't dealt with.

Not willing to risk a conflict with the second-largest army in NATO, Assad expelled Ocalan from the country. After fleeing to a number of third countries, Ocalan was eventually captured in Kenya by the Turkish security services in 1999 and has remained in prison in Turkey ever since.

Turkish incursions

Since the beginning of the Syrian war in 2011, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), a group with ideological and organisational links to the PKK, has sought to carve out an autonomous region in northern Syria. It was a move which alarmed Turkey, who believes any PYD entity would become a launchpad for attacks on its borders.

In 2016, the Turkish military and allied Syrian forces launched Operation Euphrates Shield and entered northern Syria with the express aim of defeating the so-called Islamic State (IS) group that still controlled chunks of the country. However, the PYD argued that they were the ultimate target of the Turkish forces.

Since 2015, the US had supported the PYD's armed wing, the People's Protection Units (YPG), in the fight against IS, viewing them as the most effective fighting force on the ground. As the main component of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), the YPG managed to wipe out much of the group's territorial control in the north, including capturing their "capital" Raqqa.

However, anyone who had hoped that the US government's backing would include protection from Turkey was disappointed - then US Vice President Joe Biden warned the YPG against expanding west of the Euphrates River if they wanted to keep Washington's support, effectively preventing the creation of a contiguous entity linking the Kurdish "cantons" in the northeast and northwest of the country.

Operation Olive Branch in 2018 saw the Turkish army and its allies entering the northwestern region of Afrin and overthrowing the YPG presence there, leading to widespread lawlessness and what some said was demographic displacement of the Kurdish population.

Although the US had said it was "deeply concerned" about the operation, then Defence Secretary James Mattis said Turkey had "legitimate security concerns".

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.