Impartial or ambivalent? Lebanon's protests put security forces in the spotlight

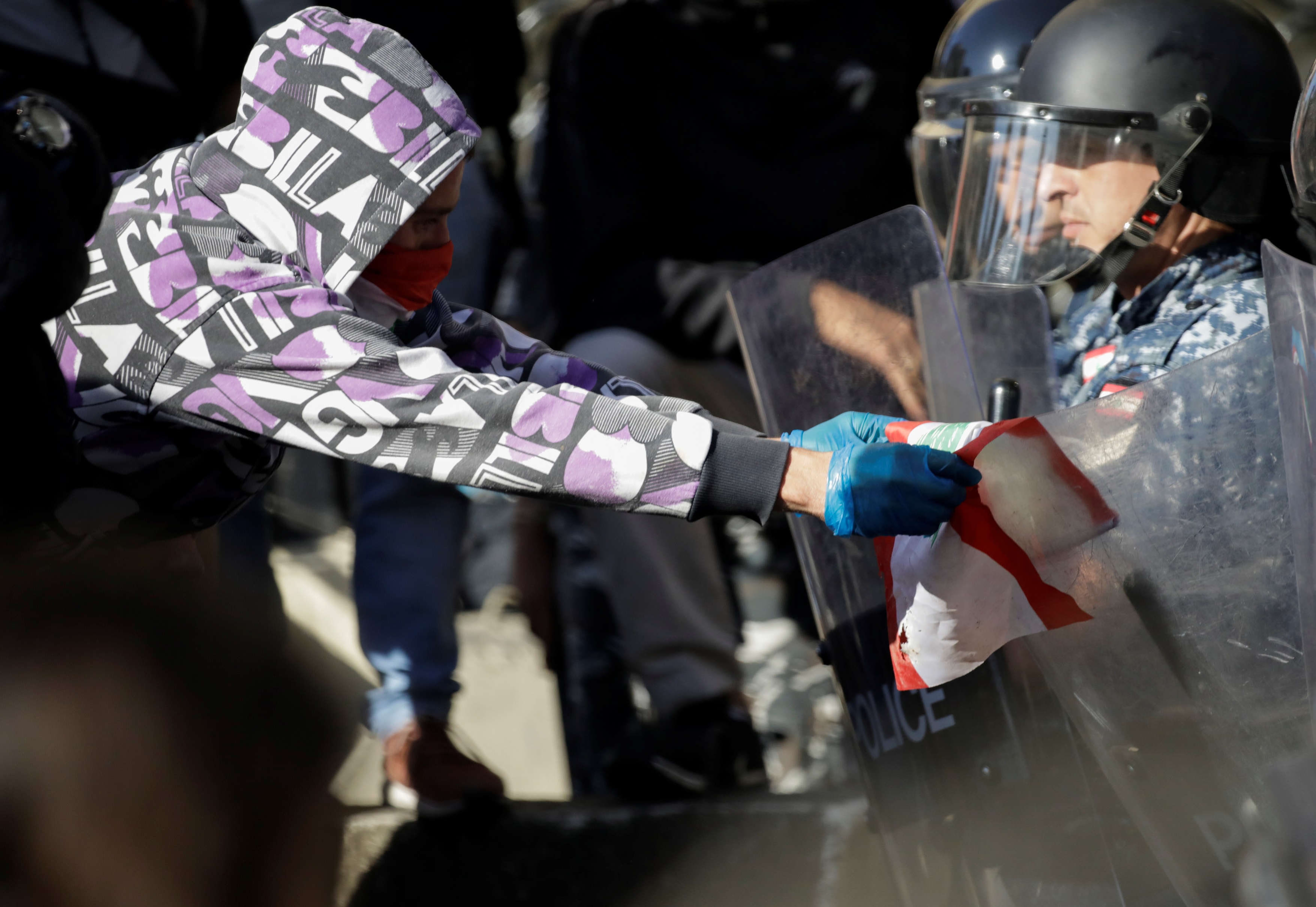

When a group of anti-government protesters gathered at a roadblock near downtown Beirut, a sense of anxiety could be felt in the crowd as security forces appeared and formed a barrier between them and an opposing group of Hezbollah and Amal Movement supporters.

Since protests first erupted in Lebanon eight weeks ago, the country's security forces have repeatedly been accused of using excessive force against peaceful protesters while turning a blind eye to violent acts by their rivals.

So when Hezbollah and Amal supporters, who accuse protesters of making offensive comments about their party leaders, began throwing rocks at anti-government protesters, anger gripped the crowd when the army showed restraint, even as one of their soldiers was wounded.

Frustrated at what they saw, one protester picked up a rock and hurled it back angrily, only for baton-wielding soldiers to rush at him and hit him instead.

The incident came to mirror previous events since the uprising - often dubbed the "October Revolution" - first gripped the country.

Hanan, a protester in Beirut, told Middle East Eye that the security forces had markedly different approaches to protesters and supporters of Hezbollah and the Amal party.

"They crack down on those who are powerless but leave the thugs [alone]," she said.

"They didn’t detain a single thug … because they are backed by certain political parties."

Lebanese forces have been accused of routinely cracking down on anti-government activists with sound bombs, tear gas and both rubber-coated and live bullets.

The demonstrators, who have set up roadblocks and pickets across much of the country, say they are peaceful and won’t end their activities until their demand for an overhaul of the country's supposedly "corrupt" and "sectarian" political system is met.

However, with the protests now in their 45th day, the carnival-type atmosphere that first accompanied the rallies appears to have given way to a far more cautious one.

"When the protests started, the streets felt safer than ever," said Farah, who preferred not to give her surname.

Having routinely attended protests in Beirut and other towns, she says she and other protesters no longer feel protected.

"I'm angry because now I have to be cautious."

'Backfire massively'

As the protests show no signs of abating, incidents of violence against protesters appear to have worsened.

Recently, the army admitted that they arrested some 20 people in one night alone.

Speaking to local television channel al-Jadeed, some of the released said they were beaten prior to or during their detention for chants the army found provocative.

Just last week, five young boys, three of whom are minors, were arrested in the town of Hammana for tearing down a political poster.

The boys were reportedly detained for several hours before being charged with vandalism and violating Article 317 of the penal code, "inciting strife among society", which is punishable by one to three years in prison.

"Thugs who terrorise and attack ... - even the army - run free ... but peaceful protesters ... are brutally beaten, kidnapped, and arrested," Farah said.

Bachar el-Halabi, a Middle East researcher at the American University of Beirut, said he expected more violence from both the political partisans (supporters of Hezbollah and Amal) and the security agencies in an effort to end the protests.

"The state will try to increase the use of violence … but this strategy will backfire massively."

He added that by staying relatively peaceful, the protesters had “outsmarted” their adversaries.

Between force and restraint

Lebanon's security agencies, primarily the Internal Security Forces and the army, have said that while they will protect people’s rights to protest peacefully, they will not tolerate roadblocks or the destruction of public or private properties.

Compared to the garbage crisis protests in 2015 where excessive force was far more prevalent, this bout of protests has seen emotional videos emerge of protesters and soldiers hugging each other.

Maha Yahya, the director of the Carnegie Middle East Center, said that security forces, especially the army, were in a tricky situation between following orders and protecting people.

"The army is given their marching orders to open roads by [the] political leadership," Yahya told MEE.

"But at the same time, they’re bound by duty … to protect [the] protesters. They're torn between the two."

Roadblocks have especially been a point of contention between the government and protesters.

While the government and security agencies see them as a violation of freedom of movement, protesters claim that they allow ambulances and security officials to go through, while providing a detour for everyone else.

Human rights organisations have also refuted government claims, saying that the free flow of traffic is not necessarily equated to freedom of movement.

'Vicious circle'

Yahya said that one of the biggest takeaways from the approach taken by the authorities was the contrasting way with which they dealt with anti-government protesters and partisans.

The "presence of undercover agents" from various institutions is "quite visible and palpable" she said, and it's being paired with "the kind of thuggish behaviour" targeted at protesters by partisans.

"Combined, I’m not surprised protesters wouldn't feel as safe as they did before."

Despite concerns from protesters and human rights organisations, Raya el-Hassan, Lebanon’s caretaker interior minister, feels security forces have been impartial.

Speaking to CNN in October, Hassan described an attack on protesters and their encampments by pro-Hezbollah and Amal partisans as two protest groups clashing.

"Sometimes bad things happen, and I wish it didn't," Hassan said.

Her comments appeared to contradict local watchdog Legal Agenda which claimed that the security forces and the army were given orders to allow the attack to take place uninterrupted.

Describing the incidents of violence as a "vicious circle", Hanan, the protester, says this is a deliberate scare-tactic to get protesters to leave the streets for good.

"[The government] thinks the people will back down if they scare them with their thugs. But things have changed."

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.