Survivors of torture camp want justice after 'butcher of Khiam' returns to Lebanon

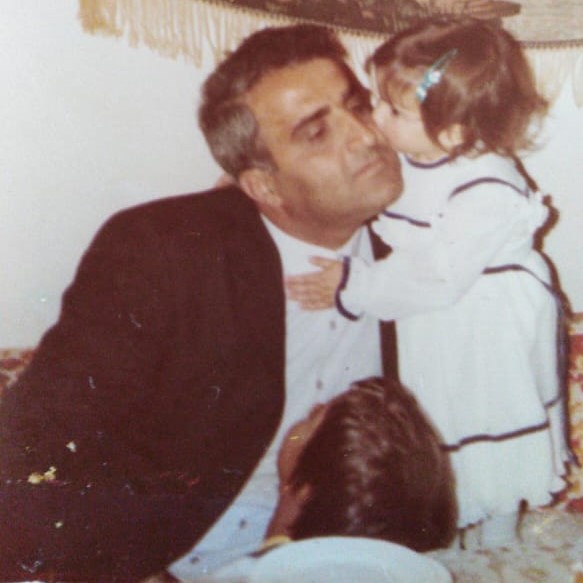

Every time Ola Hamzeh misses her father, she drives through the mountainous villages in southern Lebanon, walks into a French-built fort converted into a detention centre in the town of Khiam, stands next to an electric pole there, and recites Quranic verses for his soul.

Her father, Ali Abdallah Hamzeh, spent the last hours of his life in March 1986 tied to this pole in what would eventually become the most notorious detention centre for torture and ill-treatment in then-Israeli-occupied southern Lebanon: the Khiam camp.

His jailers, members of Israel’s proxy militia, the South Lebanon Army (SLA), never handed over his body to his family. He was 42 years old, a father of three children, and a teacher at a local school in the village of Jmayjmeh in southern Lebanon. Former detainees say he died within two weeks of his abduction.

In May 2000, Israeli forces retreated from southern Lebanon thus ending a 22-year occupation. The overwhelming majority of Lebanese militia members who ran the Khiam camp, which had been set up in 1985, fled to Israel along with thousands of other SLA members. Ali Abdallah Hamzeh’s family was left without answers.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Now Ola has renewed hope that she could find out where her father’s remains are located.

The 'butcher of Khiam'

Earlier this month, the man who reportedly served as the top military official at the Khiam camp for around a decade returned to Lebanon, apparently confident that the 15-year prison term to which he was sentenced in absentia in 1996 was no longer applicable due to the statute of limitations.

Amer Elias al-Fakhouri, dubbed the "Butcher of Khiam", arrived in Lebanon in early September using his American passport. News of his return without being immediately arrested sparked outrage, with former detainees and others staging protests demanding that he face justice.

Fakhouri was arrested and referred to the Military Tribunal on 13 September over accusations of joining enemy forces, possessing an Israeli ID, and torturing Lebanese nationals resulting in their deaths.

Fakhouri’s arrest was based on the Lebanese Law 194 of 2011, which states that there is no statute of limitations for members of the SLA who crossed into Israel, according to lawyer Hassan Bazzi, who represents six former detainees who recently filed a complaint to the public prosecutor in the southern city of Nabatiyeh against the former jailer.

'All I want is for [Fakhouri] to tell me where my father is buried'

- Ola Hamzeh, daughter of a former detainee

The law stipulates that former SLA members should be arrested upon their return to Lebanon, handed over to the Lebanese army and tried for their crimes.

“I do want Amer al-Fakhouri to face justice. But even if the Lebanese state doesn’t give us justice, I believe that there will be divine justice. For now, all I want is for him to tell me where my father is buried,” Ola, who last saw her father when she was three, told Middle East Eye.

Hamzeh and all other individuals detained at the Khiam camp, including at least eight people who died while in detention, were held without any legal charges, warrants, court hearings or sentences.

They were not allowed access to the outside world during open-ended detentions that lasted for months and years.

In the 1990s, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch said Israeli intelligence had direct involvement in the Khiam camp, despite attempts by Israel to distance itself from responsibility for the crimes committed there.

An affidavit submitted by the Israeli defence ministry to Israel’s High Court of Justice in September 1999 stated that the Khiam camp was administered, maintained and guarded by the SLA. The SLA itself was financed and armed by Israel.

Fakhouri was one of two top officials at the Khiam camp that had a dual command structure. He was the prison commander in charge of both the camp’s military personnel and the sections housing detainees.

He reportedly served in this position for at least a decade, according to former detainees, and was replaced approximately two years before the Israeli withdrawal from southern Lebanon in May 2000.

Another top official, Jean Homsi, also known as Abu Nabil, was the chief interrogator at Khiam camp.

Homsi was tasked with interrogating detainees shortly after their arrival and it was during this stage that torture took place to extract confessions.

Fakhouri and Homsi crossed the border into Israel when Israeli forces withdrew from Lebanon. Amer al-Fakhouri eventually went to the United States and became a US citizen.

Former detainees accuse Fakhouri of commanding the camp when daily conditions were at their worst, particularly between 1986 and 1995, the year the International Committee of the Red Cross had access to the detention centre and organised family visits.

But Fakhouri’s family says he is neither a "butcher" nor a collaborator, although they acknowledge that he directed the Khiam camp. In a statement released last week, his family said that Fakhouri worked hard to “provide the needs of the detainees” and that he did so at the expense of spending time with his family.

Israeli air strikes destroyed what remained of the Khiam camp during the war between Hezbollah and Israel in July 2006.

The price of the sun

“Amer was in charge of managing and controlling the prison, and he didn’t use the space he had to improve our situation. He was in charge of the quality of our food, how many times we could bathe a month, and how many times we could go to the sun room,” Riad Issa, who was detained from September 1990 to October 1992, told MEE.

Issa was detained after a set of improvements were put in place at the Khiam camp as a result of what former detainees refer to as a two-day “uprising” they staged in November 1989.

He said the detainees were allowed to be in the sun once or twice a week, only occasionally three times a week, for no more than 15 minutes at a time.

'The conditions improved from being very, extremely inhumane to extremely inhuman'

- Abbas Qabalan, former detainee

Testimonies on accessing the sun sometimes varied depending on which section of the camp a detainee was held. Another detainee said they could see the sun only once every week or ten days.

Afif Hammoud, who was released in June 1998 after 10 years in detention, said: “Sometimes a jailer would allow us in the sun for the few minutes it took him to smoke his cigarette.”

Before the uprising, detainees were allowed to what they call the “sun room”, an area with access to the sun, once or twice a month irregularly in the summer and not at all in the winter.

“After the uprising, conditions improved from being very, extremely inhumane to extremely inhumane. It was never minimally acceptable,” said Abbas Qabalan, who was detained from September 1987 to June 1998 and witnessed various stages of detention conditions at the camp.

Qabalan told MEE a single plastic bucket would be placed inside a cell to be used as a toilet by four to seven people, only to be emptied out every two to three days.

After the uprising, the jailers started emptying the bucket “probably every day”.

However, these improvements cost the lives of two detainees after the jailers, who the former detainees say operated under Fakhouri's authority, used gas-releasing weapons inside three sections housing detainees.

Banging the metal doors

The uprising began when detainees in "Prison No 3" - one of the sections of Khiam camp - began a hunger strike demanding better living conditions at the camp, taking turns lying on their backs and banging their feet against the cell’s metal doors.

“The jailers and Amer al-Fakhouri told us to stop, but we did not. We felt that we could no longer get on with this kind of degrading treatment. It was not worth living for.

"We decided that we either live in dignity or we die,” said Hammoud, who was detained in one of several cells in Prison No 3.

Qabalan, who was detained in a cell in "Prison No 4", said he and other detainees heard the shouting and banging of doors coming from No 3, and it encouraged them to do the same.

A gas cannister was thrown in Prison No 3, followed by another thrown in No 4, both of which were indoor facilities, detainees said.

'Lebanese courts should either rule justly or let the judges go to the Khiam camp and stay there, only then will they feel our suffering'

- Afif Hammoud, former detainee

The jailers eventually unlocked the cell room doors, allowing the detainees to go to a courtyard as they were all gasping for air, before leading them back to their cells.

The following morning, the detainees were taken to a courtyard and beaten over several hours by a group of jailers and torturers as a punishment for their protest.

Some of them were then transferred to "Prison No 2" before sunset.

The detainees asked the jailers to help Bilal al-Salman, who had been having difficulty breathing since inhaling the gas two days earlier, Qabalan said. But the guards were indifferent.

Salman died and detainees in Prison No 2 started to bang the metal doors to protest his death. The jailers once again used a gas weapon to quell the protest, leading to the death of Salman’s best friend, Ibrahim Abu al-Izz.

“No jailer could use such a weapon at Khiam camp without taking orders from Amer al-Fakhouri,” affirms Hammoud. “Lebanese courts should either rule justly or let the judges go to the Khiam camp and stay there.

"Only then will they feel our suffering.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.