Libya: How a sinking migrant boat's pleas for help fell on deaf ears

Activists say that state actors failed to respond quickly to a sinking ship that left over 60 people presumed dead off the northern coast of Libya on the night of 13 December.

The overcrowded dinghy reportedly sank, as high tides engulfed the vessel after it left the Libyan coastal town of Zuwara.

According to survivors, 86 people were believed to be on board the vessel, including women and children, the majority of them from Sub-Saharan Africa.

The International Organisation for Migration (IOM) stated that 25 survivors had been rescued and sent back to Tariq al Sekka detention centre in Libya.

Alarm Phone, a volunteer-run hotline for boats in distress, was in contact with the boat for most of the incident.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

“We received the first distress call at 5pm,” Alarm Phone activist Britta Rabe told MEE. “They said they were on a rubber boat and the sea was very rough.

“It was also very windy, we didn’t expect any departures that day, so it was clear they were in a very dangerous situation. They were panicking, ” Rabe said.

Alarm Phone sent multiple alerts to the Italian, Maltese and Libyan authorities, as well as the Sea-Eye rescue vessel, the only available civil fleet, which was 12 hours away.

An hour later, it managed to reach a Libyan officer who agreed to send a patrol boat.

'The moment we do one rescue... we are forced to leave the area, even though the weather conditions mean there may be other cases'

- Virginia Mielgo, MSF project coordinator

The boat was never sent because of bad weather, although Alarm Phone said it was aware that at least two Libyan rescue boats were out at sea that day, intercepting at least three other boats.

At 6pm, Alarm Phone received a final call from the boat which said, “We are losing our li[ves] here!”

At 9:40 pm, the Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre (MRCC) in Rome ordered a supply vessel, the Vos Triton, to the boat in distress.

Alarm Phone noted that the vessel was ill equipped to perform a rescue and later lost contact with the boat.

“We didn’t know what had happened,” Rabe said. “We tried many, many, many times to call all the different phone numbers [for] the Libyan Coast Guard to find out what happened.”

The Libyan Coast Guard eventually told Rabe and her colleagues that 25 people had been rescued by the supply vessel.

“It was very unclear, because [the people on the boat] had told us that there were more than 50 people aboard," Rabe said. “So we wondered for a very long time what happened to the rest.”

It was only when they saw a tweet from IOM the next day reporting that 61 people were missing after a wreck, that they knew what had happened.

No accident

The absence of rescue boats patrolling the crossing that day was no accident.

The Medecins Sans Frontieres-chartered rescue vessel, the Geo Barents, had been patrolling the area near the wreck just two days before.

When it received the alerts from Alarm Phone, it was already en-route to Genoa with a near empty ship, to disembark a rescue.

A raft of anti-migrant legislation introduced by far-right Italian Prime Minister Georgia Meloni compels civil boats to immediately disembark following a rescue to designated ports further away in northern Italy.

Campaigners have said the policies have widened an already huge “rescue gap” in the central Mediterranean waters.

"We were leaving already with just 36 people, not even 10 percent of our actual capacity," MSF project coordinator Virginia Mielgo told MEE. "We could have stayed longer because we have the capacity to rescue more than 600 people."

"The moment we do one rescue... we are forced to leave the area, even though the weather conditions mean there may be other cases," she said.

If they stayed, the crew risked being impounded and fined, as they were in February.

Mielgo highlighted that performing a rescue in the poor weather conditions would have been safer with a rescue vessel rather than a supply ship.

"We have the capacity and the technical expertise to perform a rescue in such a complicated situation," she said.

The crossing is already the world’s deadliest migration route, with over 2,500 migrants dead or missing after attempting the crossing as of September this year.

This is double last year’s figures, the highest number for the period since 2016.

Tunisia and Libya emerged as the main departure points, with more than 102,000 people departing from Tunisia in 2023, a 260 percent increase on last year.

At least 45,000 have attempted the crossing from Libya this year.

The surge in departures from Tunisia came amid a spike in racial violence targeting Sub-Saharan African immigrants.

Meanwhile in Libya, thousands of refugees and migrants are detained in what Amnesty International described as “hellish” conditions where they face beatings, sexual violence, extortion and forced labour.

“We saw recently that people even depart in very bad weather,” Rabe said.

“I think this [shows] that people really need to flee from Libya.”

EU complicity

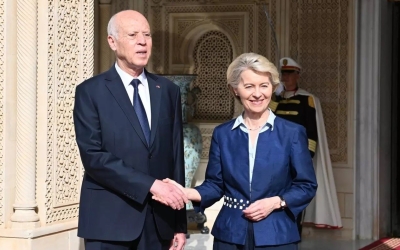

The news of the wreck comes amid a flurry of controversial anti-migration deals signed by the EU with North African countries.

A contentious migration pact between the EU and Tunisia, which would have seen Tunisia curb migration in exchange for financial aid, unravelled after Tunisia returned a €60m payment in October.

A similar deal signed with Egypt in 2022 will see France deliver three search and rescue vessels to the Egyptian coastguard.

The EU has also trained and equipped the Libyan Coast Guard since 2016, drawing accusations of complicity in atrocities committed by the Libyan Coast Guard against migrants during interceptions at sea.

A recent Lighthouse Reports investigation revealed that Frontex, the EU border agency, had been “systematically sharing” coordinates of refugee boats with a "pirate" vessel run by the Tariq Ben Zeyad brigade, a Libyan militia group known for kidnap and torture.

The investigation found that the collaboration could violate international law.

In June, an overcrowded fishing trawler capsized off the coast of Pylos in Greece, killing more than 600 people. A series of investigations alleged that the Greek authorities were aware of the imperilled vessel hours before it sank and failed to conduct a rescue.

On 6 November, Meloni announced a “historic” deal with Tirana to establish detention centres in Albania to accommodate people rescued at sea by Italian boats. However, Albania’s constitutional court later suspended ratification of the deal after appeals argued that it breaches the Albanian constitution and international conventions.

On Saturday, UK PM Rishi Sunak said that he and Meloni would do “whatever it takes” to “stop the boats”, agreeing to co-fund a scheme that would return migrants stranded in Tunisia.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.