Libyans in south Tripoli find themselves on the frontline of Haftar's war

At night, Omar’s* house in Tripoli’s southern suburbs shakes, as shells fall all around it. When his family of nine emerges in the mornings, they find evidence of the raids the night before.

“Often, we find shrapnel in the outer wall of the house,” the 37-year-old government employee tells Middle East Eye from his office, fraught from worry.

When eastern commander Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA) began pushing towards Tripoli in April, Libyans fleeing the assault sought shelter in the capital’s southern neighbourhoods.

Many residents of areas first affected predicted a short flare-up and temporary clashes as seen before.

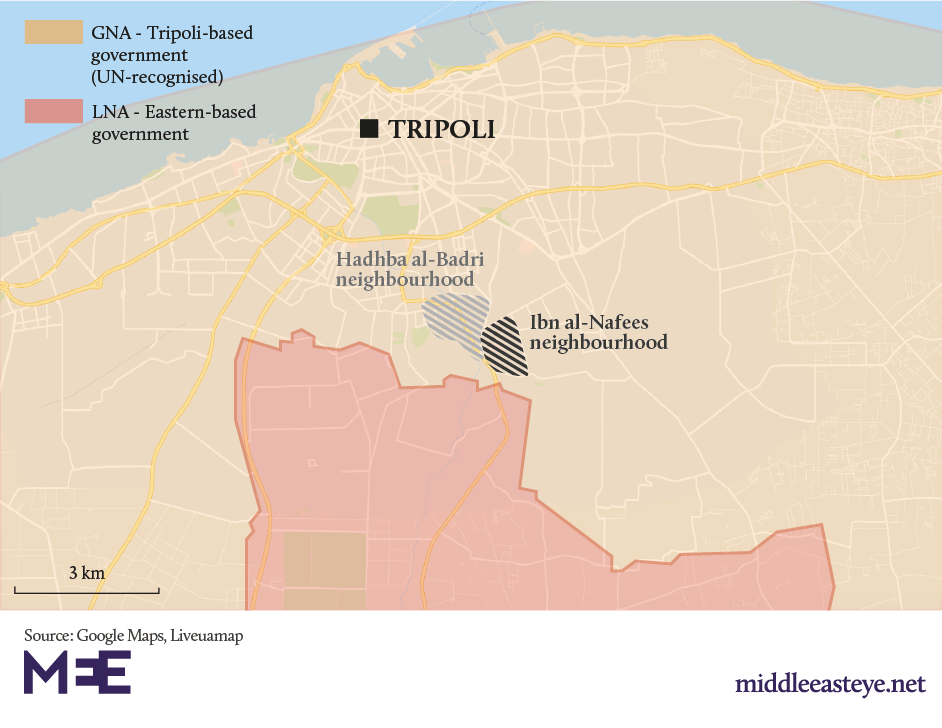

Believing they would return to their homes imminently, hundreds took temporary shelter in residential areas around south Tripoli’s Ibn al-Nafees and al-Shouk roads, where rent was affordable and their children’s schools accessible.

Now those same districts are on the front line, as the LNA attempts to wrest control from the UN-recognised Government of National Accord (GNA), displacing ever more people towards the city’s centre.

More upmarket neighbourhoods have now also become both the recipient of fleeing Libyans and recently the target of shells. Once-peaceful streets are packed and anxious.

Multiple displacements

Mohammed, a father of four, left his home in Khallat al-Furjan in April, first moving to relatives’ home in Tripoli’s al-Hadba al-Badri neighbourhood, before settling in Ibn al-Nafees.

He and his family took only their official papers and a couple of cases of belongings, leaving most of their possessions behind.

“We thought that these clashes would be temporary, and that is why we headed to our family’s home in the al-Hadba al-Badri area and stayed in my parents' house for a while,” he told MEE.

“But since the war took too long, we decided to search for shelter to rent elsewhere, and after a remarkable effort we were able to get a house in Ibn al-Nafees last July.”

In October, fighting around Ibn al-Nafees forced Mohammed and his family back to al-Hadba al-Badri, which now is increasingly a target.

“Unfortunately, we were unable to find a house to rent at a reasonable price, as all prices are exaggerated and illogical, especially for people with low incomes,” said Mohammed.

Al-Hadba al-Badri is a popular and densely populated neighbourhood with increasingly prohibitive property prices for the young. Today, with more and more people fleeing the LNA and settling in al-Badri, the average rent for an apartment is 2,000 Libyan dinars ($1,400) a month, over half the average monthly salary.

Unable to buy or rent, young families tend to build extra floors on the homes of their parents.

Many families displaced from elsewhere and lacking funds have resorted to living in buildings still under construction, exposed to the elements and plummeting shells.

Victims of war

At lunchtime on 27 January, a shell fell into al-Hadba al-Badri, killing four children between the ages of nine and 12.

Three of them, Anas al-Ghazawi, his brother Abdul-Malik, and Zakaria Jamal, had been displaced to al-Hadba al-Badri from al-Khalah by the LNA assault. The fourth, Sanad al-Orabi, had befriended the displaced children and they had been playing in the street.

Clashes nearby had people on edge that morning, Orabi’s mother Mabrouka said.

“We received a call from my son’s bus driver who told us that he was unable to reach our house because of the renewed clashes,” she recalled.

“My son was unable to go to school, so he changed out of his school uniform and went to play outside the house with neighbours’ children.”

Hearing the sound of an explosion, Mabrouka ran out into the street to find her son bleeding from his head.

“I also saw the rest of the wounded children trying to crawl. I screamed ‘My son is dead, try to save the rest of the children’,” she said.

UNICEF, the United Nations’ children’s agency, condemned the attack.

“UNICEF calls on all parties to conflict to abide by their obligations under international humanitarian law and international human rights law to protect boys and girls at all times,” it said in a statement.

But attempts at engineering a peaceful settlement between Haftar and the GNA, who are both backed by various foreign countries and actors, is slow and even abortive.

Talks in Geneva this week between the two warring parties have stalled, with an LNA attack on Tripoli’s port prompting the GNA to withdraw from the indirect dialogue.

Swelling numbers

Meanwhile, the fighting and displacement continues.

According to statistics released by the International Organisation of Migration on 9 January, an estimated 150,000 people have been displaced from Tripoli’s outskirts since the offensive began.

Belgasem al-Qantari, an official in the GNA’s ministry for the displaced, told MEE that 120 million dinars ($84.5m) has been allocated by the Tripoli government to provide those fleeing the conflict with necessities such as food and medicine.

The main dilemma, he said, was finding accommodation for them.

“We are currently working with a number of companies to supply ready-to-install pre-fabricated homes, to use them as houses until the war is over,” Qantari said.

However, Libyans such as Mohammed are fast running out of options.

If things continue to get worse, Mohammed says his family will be forced to flee to neighbouring Tunisia, where rent is cheaper, power supply is constant and the threat of bombs falling from the sky is non-existent.

Though there is a nominal ceasefire currently in place, civilians in al-Hadba al-Badri and surrounding neighbourhoods are still familiar with the whistling of shells overhead.

Many families are terrified to leave their homes, thinking they could be struck at any minute.

Meanwhile, life continues relatively normally in more central areas of the Libyan capital, with people for the most part able to work and go to school as normal.

For many, that sense of normality amidst the chaos has rooted them in their neighbourhoods. Though it is unclear how long that will last.

Mohammed, for one, is reluctant to flee to Tunisia, uproot his family once again and totally disrupt his children’s education.

“I have no solution but to stay in my family's house in al-Hadba al-Badri, as I cannot go to Tunisia, where I will need to work to provide rent there,” he said.

“So, by travelling, my livelihood will stop, and this is a dilemma for which I have not found a solution.”

*Some names have been changed.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.