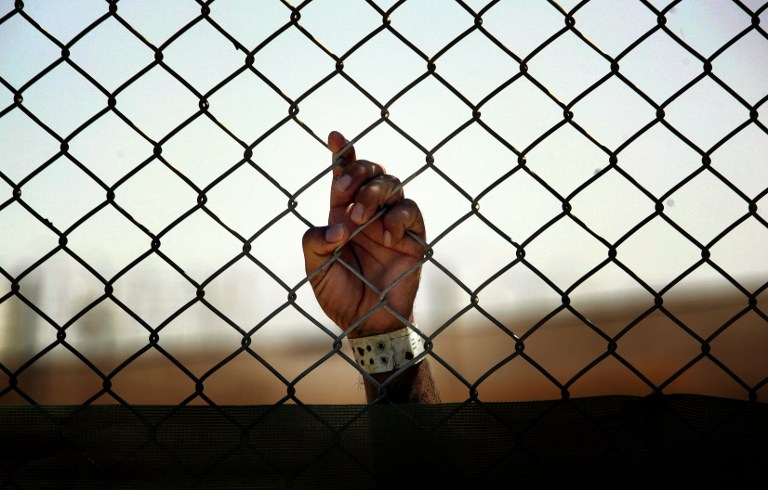

Life and death in an Islamic State prison

ERBIL - Mustafa* was scheduled to be executed on 22 October, upon orders of the Islamic State (IS).

That same night, the 32-year-old policeman scrawled his last wishes onto a piece of paper and addressed them to his eldest nephew, the son of his brother who was beheaded by IS’s predecessors in 2006.

After his brother’s murder, Mustafa took his sibling’s five orphans and his widow into his home and has been looking after them since.

“I told him I would be killed tomorrow and that he should take care of his brothers, his mother,” he told Middle East Eye at a security facility in the Kurdish capital of Erbil.

In his final hours, the young policeman found comfort in the Quran, weeping into the pages of the holy book as he waited for sunrise and his certain death.

But Mustafa was never faced with the harrowing finale. Instead he was jolted out of his state of despair at two in the morning when he heard the rumble of helicopters flying overhead.

That night 69 hostages including Mustafa were freed from IS captivity in a joint Kurdish-US military raid near the northern Iraqi town of Hawija.

A US commando was killed and four Kurds were wounded during the mission.

“I was scared, I didn’t know what was going on. We heard the fighting,” he recalled.

The Kurds, who had hoped to find and free captive peshmerga soldiers were met by local Arabs – most of whom were former members of the Iraqi security forces – and imprisoned members of IS.

“They broke the door down and asked if there were any peshmerga. We said no and they shouted: don’t be scared we’re here to help,” said Mustafa.

Revenge against IS

This was not Mustafa’s first time in an IS prison. In March 2015, four armed men burst into his house at night, blindfolded him and ripped him away from his family – he was accused of informing Kurdish forces of IS positions, a "crime" which Mustafa had, in fact, committed.

When asked why he chose to risk his life to report on IS, he said simply: “It was my revenge against IS because they killed my brother.”

Wrecked by war and social unrest following the US invasion of Iraq, the area of Hawija became a hub for Sunni militants who frequently targeted US and Iraqi forces – including several of Mustafa’s family members.

Blindfolded and unable to see where he was or who was in the room with him, Mustafa recalled only the cold water being poured over him and the pain that ensued when electric cables were pressed onto his bare skin.

“When I fainted they woke me up by electrocuting me,” he said. But his interrogators were unable to obtain the information they needed from him and released him after 20 days.

His second stint in captivity began on 20 July in the midst of Iraq’s stifling summer heat and lasted until the raid.

The makeshift prison in which he spent three long months had once been home to a local judge who had fled to Kirkuk when IS took Hawija. IS members refer to it as 'Q8' on the radio, said Mustafa.

Some 35 men were crammed into a tiny room with limited ventilation, while other prisoners could be heard in neighbouring rooms.

According to Mustafa the prisoners were mostly policemen and soldiers who had been caught feeding information to Baghdad, the Kurds or the Popular Mobilisation force. A few others were unruly IS members who had failed to adhere to the group’s rules.

A confession

Over the next three months, Mustafa was subjected to eight interrogations, each session lasting between two and three hours.

Ten days before the Kurdish-US raid, the men holding him threatened to arrest his children and his brother’s children and kill them – Mustafa cracked, confessed and was sentenced to death.

“They were going to kill me anyway so I wanted to protect the children,” he recalled.

During his time in captivity, men were often taken away and never seen again. But while it is uncertain whether some of them were killed or released, Mustafa was adamant that at least four had been killed and buried in a communal grave.

“We heard the sound of digging behind the room I was in. I thought they were repairing something,” explained Mustafa.

The following morning, the men were taken away; soon after, gunshots rang through the air. “We found out later that they had been killed and put in the hole," he said.

Like Mustafa, 31-year-old Tarek* was also imprisoned for relaying information to IS's enemy; in his case it was to the Iraqi government.

Before being accused of spying on IS, Tarek had been in prison five times as a result of a personal dispute with a local man whose cousin had joined IS.

According to Tarek, IS was able to control Hawija because of the widespread support the militants received from the residents.

“At first they asked us to give them our weapons. When they knew we had no weapons they changed their behaviour – they became harsh,” he said.

Escaping IS

Tarek was kept in the same room as 36-year-old Malek*, who had been caught trying to flee IS territory.

An increasing number of residents have recently crossed over from IS areas of control into the Kurdish region and often on to Europe, in search of safety and financial stability.

The ongoing mass exodus to Europe has prompted IS to tighten its noose on the population, whose taxes largely contribute to the group’s revenue.

“They caught me before I could even leave my house,” said Malek, who had already been arrested twice, accused of criticising IS.

“They would bring us lunch, take one of us outside and start torturing him - we would hear his screams and lose our appetite,” explained Malek, who remained behind closed doors for a month before he was freed during the raid.

The head of the prison, a harsh-tongued man from Diyala, he said, would sometimes torment the men by telling them to expect violent beatings on the days in which they were served a good meal.

“If we asked for Panadol, they offered us a bullet,” said Malek, whose mischievous grin barely left his face as he recalled the horrors of IS captivity.

All three men have had to leave their families behind, unable to contact them for fear of putting their lives at risk. Kurdish security officials are still debriefing the prisoners, but told MEE that once finished, the men were welcome to stay in Kurdistan - and would not be forced to return to Hawija or handed over to the Iraqi government.

Mustafa, whose two wives, 10 children and brother’s widow remain in Hawija, hopes to resume his job as a policeman in Kirkuk, eager to serve his country.

He had at times considered smuggling his large family out of IS territory, but the price of $400 per person proved too costly, leaving him no choice but to continue surviving under the rule of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

In a stroke of luck that saw him escape execution, Mustafa has also had to sacrifice seeing his loved ones – with no certainty that he will ever see them again.

*All names have been changed to ensure the safety of these sources and their families.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.