London is failing to find homes for Syrian refugees

LONDON - “London is open”, the British capital’s mayor Sadiq Khan insists.

Yet finding a home in the city for the thousands of Syrians waiting to be resettled in the UK has proved a difficult task, and acclimatising has proved a struggle for many that have been housed here.

Three years ago, the death of Alan Kurdi, a three-year-old Syrian refugee, made global headlines after he drowned in Mediterranean Sea.

The tragedy heaped pressure on European governments to do more for those fleeing Syria’s conflict, with then-UK Prime Minister David Cameron promising to resettle 20,000 refugees by 2020 through the Vulnerable Syrian Resettlement Programme (VPRS).

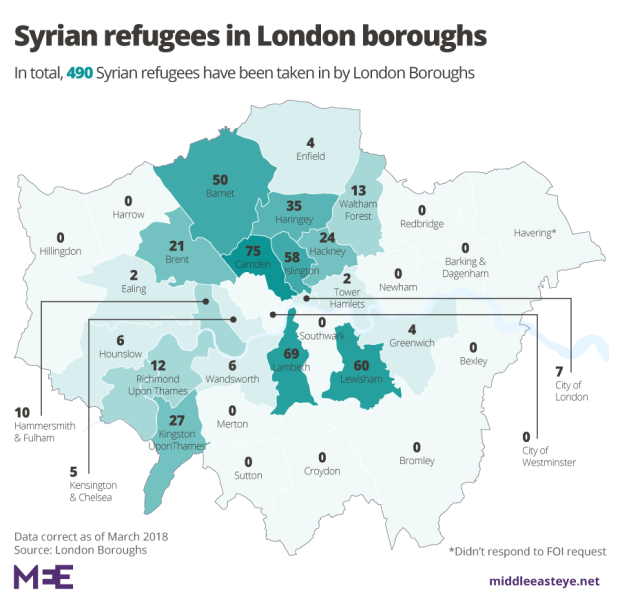

However, freedom of information (FOI) requests have revealed that the UK, far from meeting the target, has so far resettled just 10,538 refugees, with only 490 of those housed in London.

Local activists and experts warn that due to lack of housing and high rents, councils are struggling to find anywhere for refugees to live.

A paucity of homes

According to data Middle East Eye has obtained through FOI requests, Camden is the borough with the highest number of Syrian refugees, resettling 75 since the scheme began.

Some boroughs, such as Westminster, the home of parliament, are yet to take in any.

Local councils and refugees are faced with a recurring problem for Londoners: a paucity of available, affordable accommodation.However, they do have some help from international NGO Refugees Welcome, which helps locate apartments and prepare them for refugees.

The group, run entirely by volunteers, is encouraging people to rent out their flats to refugees, who have their rents paid for by the UK Home Office.

Britain suffers a severe shortage of council houses, with recent figures from Shelter, a homelessness and housing charity, showing that more than 1 million families are stuck on the social housing waiting list.

As a result, councils are turning to private rentals to house Syrian refugees.

Yet despite being by far the largest city, London has far higher rents than elsewhere in the country.

The average price of a two-bedroom flat in the capital now stands at £1,500 a month, according to a report from the trade union GMB – an amount that is offputting for many London councils.

'As in the rest of London, there is a housing crisis in Islington with a massive shortage of affordable housing'

- Kaya Comer-Schwartz, Islington councillor

Clare Burnett, a London-based artist, is a volunteer in the west London borough of Hammersmith, where only four Syrian refugees have been resettled so far.

She owns an apartment in nearby Kensington, which she rents out to two young Syrian women.

“Normally I would get probably about £380 per week for that flat and I get £260 [per week] under the Vulnerable Person Scheme, which is the Department of Social Security rent, the standard benefit rent,” she tells MEE.

Councils can claim £8,520 per refugee to cover the costs of resettling Syrians, including accommodation, administration, transport and translation.

This figure decreases significantly year-on-year, and according to the Times, councils estimate that the assistance only covers 75-80 percent of the total costs.

“That’s why it’s been so difficult for Kensington and Chelsea and some other boroughs to find properties, because people who normally get commercial rents don’t want to take a big reduction in rent,” Burnett says.

Islington has welcomed 15 Syrian households – a total of 58 people, including four babies born in the UK.

Councillor Kaya Comer-Schwartz, Islington executive member for community development, encourages any landlords with a suitable property in the borough to contact the council to make it available for refugees.

“As in the rest of London, there is a housing crisis in Islington with a massive shortage of affordable housing,” she told MEE.

“We are very grateful to local people who have come forward to offer homes for Syrian refugees.”

On the other hand, in Westminster, which has the highest renting costs and increasing numbers of homeless people, no refugees have yet been resettled.However, Simon Perfect, a volunteer with the Westminster Refugees Welcome activist group is hopeful that the council will resettle a family soon.

“I can’t confirm at this stage because we’re still waiting for the council to finalise the process for resettlement. But we know that the council is on board and wants to do it,” Perfect said.

“Once one family has been resettled, then it’s much easier to do the rest because you’ve got a success story.”

According to Westminster Labour councillor Adam Hug, however, refugees are not the council’s top priority.

“Different councils have different levels of priority to support the refugees. This has not been the top priority for this council. I can even make a political case that a different council would take a proactive approach,” he told MEE.

“However, there is a fundamental problem caused primarily by the government’s welfare policies. The gap in market rents here in Westminster is a problem. The challenge here is encouraging landlords to come forward and offer properties below market rents.”

A Westminster spokesperson told MEE that anyone who is vulnerable is a priority for the council, but reminded that the list of people waiting for social housing is a long one.

“We are currently assessing whether this scheme is the best way for us to help refugee families,” the spokesperson said.

“As an authority, we have a duty to help vulnerable people entitled to housing help, and this can be directly through offers of accommodation or working with partners like charities and housing associations.”

Struggles continue

After the families arrive in Britain, another struggle for them begins, with many finding difficulties with language and adapting to their new surroundings.

Aisha, not her real name, is a 30-year-old mother of two living in Islington with her husband and children.

She previously worked as a teacher in Idlib, a city in northwestern Syria, and left the country for Turkey in 2012.

After living in a refugee camp in the Turkish village of Kahramanmaras for two and a half years, they moved to Britain through the VPRS program.

“My husband and son were ill, and they were in hospital. A United Nations officer asked us if we wanted to go to Europe. We said ‘Yes’, but we had no idea which country we were coming to,” she tells MEE.

In December 2015, Aisha and her family moved to London, where they didn’t know anyone and couldn’t speak the language.

“The weather, the culture, the language, everything is different. We would be scared to go outside,” she says.

“We didn’t even know how to find our way around and we were waiting for the charity to come and take us away again.”

Aisha says her family relied on Google translate to communicate with the landlords and charities when they first arrived to the country.

'The weather, the culture, the language, everything is different. We would be scared to go outside'

- Aisha, Syrian refugee

“The only thing Refugee Action [a charity helping refugees] did wrong was that they didn’t take us to English classes at first, but kept us at home,” Aisha says.

She says she found the process of learning English very fast thanks to her children, who rapidly learned English at school and made their parents speak it at home.

But despite finding the language barrier less and less of a problem, finding employment is another pressing issue, and Aisha is distressed by her husband’s inability to find a job.

“We both want him to find a job here because unemployment makes him upset,” she says.

Other resettled Syrians in London said issues with language and employment made integrating difficult.

“When we first came here my husband registered at a college but I couldn’t register because they couldn't find a college for me that had daycare for the kids,” Fatima Khasan, 22, tells MEE.

“Now, for nearly three months I’ve been attending a school. But I haven't benefited a lot.”

'When we first got here we were told for a year that a charity would be responsible for us and see what help we needed, but their help was very little'

- Fatima Khasan, Syrian refugee

Khasan says she has health problems and finds it hard to go to hospital, saying her family rarely has a translator available to help.

She also says she suffers from vertigo, but authorities won’t move her from her current home on the 19th floor of a tower block.

“When we first got here we were told for a year that a charity would be responsible for us and see what help we needed, but their help was very little,” Khasan says.

Khasan, who is from Daraa, a city in southwestern Syria, has been living in London for one and a half years with her husband and two children. Her family is still in Daraa, and her husband’s is in Damascus.

“I’m still studying. Any place [for work] wants proficient English and my language isn't there yet,” he says.

Aisha is keen to return to Syria once it becomes safe again.

“Any chance to go back, we would love to live there again,” she says.

“Every single moment, we think about this. If the children grow up and the country becomes safe, we would love to go back.”

Khasan is more cautious: “I thought about it because I’m struggling here. But I can’t, because if we go back, God forbid, something would happen to my husband, and the kids.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.