In Mali, a cattle market offers refuge and hope amid fears of genocide

The Faladie cattle market in Bamako is probably the last place that Hama Diallow could imagine calling his home.

He had come here to trade cows in 2018 when his village, some 800km away in the Mopti region, central Mali, erupted in ethnic violence. Others soon followed, fleeing with just the clothes on their back and carrying babies.

They headed straight for the cattle market, a place they knew best, and many of them have been there ever since. Like Diallow, they are Fulani, an ethnic group with ancient cow-herding traditions.

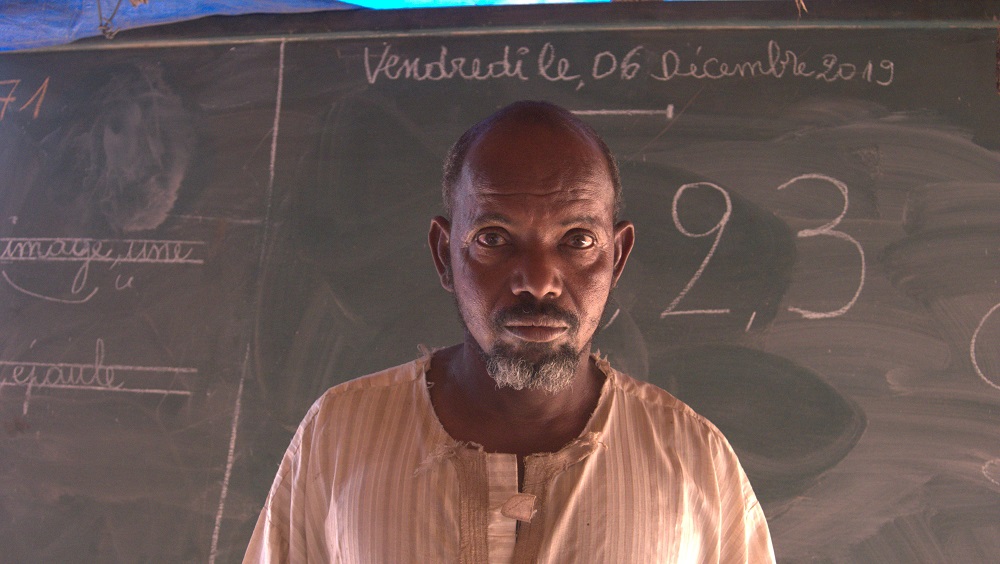

Diallow is now the leader of what has become the largest and most desperate of Bamako’s 13 camps for those displaced by the fighting. He has a look of utter resignation as he speaks. His gown is soiled with dirt and frayed at the edges.

Tensions between the Fulani and another group, the Dogon, have risen in recent years, culminating in some of the worst violence the country has ever seen.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

On 23 March last year, 160 people were massacred in the village of Ogossagou by an armed milita of men belonging to the Dogon ethnic group. Razing huts, slaughtering animals and leaving behind the charred remains of Fulani women and children, the assailants disappeared into the dust as quickly as they came.

For the most part, roving Fulani herders and settled Dogon farmers had lived in symbiosis for hundreds of years. Both sides stood to benefit whenever the great herds of Fulani horned cows grazed on the expansive Dogon farms and fertilised them.

The current violence can be traced back to 2012, when Malian security forces left central Mali and rushed north to deal with a rebellion by ethnic Toureg who had allied with a local al-Qaeda affiliate.

The battle-hardened separatists had fought on the side of Muammar Gaddafi in Libya’s civil war. After looting Libya’s armouries they trundled heavy weaponry across the Sahara back to Mali and declared independence.

In 2015, al-Qaeda-linked groups stepped into the power vacuum left behind in central Mali. After concentrating their recruitment on Fulanis left vulnerable by poverty and instability, they went after Dogon communities, inflaming communal tensions.

In turn, Dogon militia formed and launched their own attacks against Fulani villages, pushing them further into the hands of militants and setting off a cycle of tit-for-tat violence.

The situation has been compounded by a lack of accountability and a string of human rights abuses committed by Mali's army, including extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances and torture, as they go after alleged militants. Climate change has caused dwindling resources, pitting herders and farmers against each other.

The deadly ethnic conflict continues as a French-led "war on terror", in which about 5,000 French troops backed by soldiers from the "G5 Sahel" nations of Mali, Burkina Faso, Chad, Mauritania and Niger and a United Nations peacekeeping force of about 15,000 soldiers and police, concentrates its efforts on militant groups, including an affiliate of the Islamic State group, which have since destabilised other parts of West Africa.

Diallow says that some refugees have come to Faladie from as far away as Burkina Faso, Mali’s southern neighbour.

After enveloping the rickety wooden pens that hold the cows, Faladie, now home to more than 1,200 people, is extending onto a smouldering landfill site next door.

Weak children stagger among the burning refuse and swarms of flies, their potbellies the tell-tale signs of starvation. Right beside them, emaciated cows stomp their feet on the damp earth, a humus of rotting vegetables, plastic bags and hay.

Once registered, most people receive a regular package of rice, oil, spaghetti and meat - when there is food. “When food runs out they blame us for not giving them food,” Diallow said.

With hardly any governmental help, there is no running water, no toilets and little medical care. Malaria is rife.

Asked how people keep on going here, Dialow says: “People are religious. Anything that befalls them is normal. We just rely on God.”

And so life goes on, as it does anywhere else. A lady smacks a calabash against her thigh, the grains rattling inside as she prepares lunch. Another sits with a fine tooth comb braiding a girl’s hair. A young man proudly lathers and scrubs his horse to a gleaming white.

While the camp is almost exclusively Fulani, deep inside the warren of tottering tents - patched together from scrap metal, damp wood and palm leaves - there are other signs of hope, too.

For here is a community of Dogon, the very people the majority of the camp's inhabitants are supposed to be at odds with.

For three years, Dogon farmer Godiolum Dara was unable to tend to his millet, peas and peanuts after militants arrived at his Mopti village, blocking roads and preventing access to his farms.

Then one day his brother was shot dead.

When he called his brother’s mobile phone, he heard a Fulani voice down the line, convincing his family that the assailant was a Fulani.

Later he himself was ambushed and his motorcycle stolen, and so he fled, leaving behind his parents and his children.

About the violence, he says: “I wouldn’t say its Dogon versus Fulani, because the Fulanis we know would never try to kill us.”

Muhammad Dara, another Dogon man cuts in. “It's not the Fulanis, it's some people among the Fulanis doing this. We have no reason to fight with the Fulanis. They look after our cows, we tend to their farms.”

Armed men arrived on motorbikes in his town, Segou, five years ago, their heads wrapped in scarves. He believes they were aided by a village insider who steered them towards their prey.

First came the robberies. Traders on their way to market were robbed and killed. Then, one by one, the village chieftains were eliminated.

“Whether you gave them what you had or not they would kill you,” he said. “They can kill people just for sandals.”

Now that fear had been sown in the town, the raiders began to demand villagers adhere to their interpretation of Islamic law, said Dara, who is a Muslim Dogon.

“After every Friday afternoon prayers they block the door and make you stay inside to to read the Quran whether you can read it or not. You stay there until the sunset prayer. If you try to leave they will kill you. If the imam tries to say anything they will kill him.”

As for Christian Dogons, he said, “nobody goes to church, they will just burn it”.

To add to the confusion of this conflict, Dara says the man who held him up at gunpoint and took away his animals, was himself a Dogon.

His words speak to the uncertainty of knowing who is responsible for the violence, in a conflict in which the division between ethnic militia and militant groups can be fluid and where hardened criminals, trafficking in drugs and people, are also known to roam.

“We don’t know where the war is coming from or who the enemy is,” Dara says.

Communal violence in central Mali claimed the lives of at least 340 civilians in 2019 , according to Human Rights Watch. Of those killed, 284 were Fulani and 56 were Dogons.

Fulani leaders now openly speak of genocide against their community, drawing comparisons with Rwanda. Their fears are worsened by hostilities the group - Africa’s most extensive - face in neighbouring countries.

"Fulaniphobia", an irrational fear of Fulanis and a questioning of their loyalties has, they say, seeped into the local and international press and political discourse.

In 2015, a crop of young and enterprising Fulanis set up the organisation Pinal, with the aim of countering the threat of genocide in central Mali. It encourages reluctant Fulani parents to send their children to school, which they see as a buttress against the lure of militants, and has lobbied the government to do more to avoid the loss of life in central Mali.

In 2018, the group set up a displaced persons camp on a strip of land on the outskirts of Bamako, offering people a respite from the chaos and rubbish of Faladie.

“We came here because [Faladie] isn’t a place that human beings should stay, it’s for animals,” said Kola Cisse, who heads up the camp and is a co-founder of Pinal.

Built on a clearing in the woods, the Senou camp is home to more than 600 people living in tents arranged along a neat grid network. Self-reliance is a key part of the ethos here, Cisse explains, and points to a group of women carefully cutting blocks of homemade soap, which they will later go to sell in town.

An abandoned building has been daubed with bright paint and turned into a school. Farming and animal rearing projects are on the horizon.

Media campaigns by the Pinal team have attracted vital help from the UN and Medicins San Frontieres, which has built 20 toilets, water towers and offered medical treatment for a while. But food, water and medical shortages persist, and government assistance is not always what it seems.

“The government help is too political. They bring one sack of rice and then bring all the local TV stations to show that they’re helping, but they need to do more by giving them work, not just food,” Cisse said.

Pinal sees dialogue between Dogon and Fulanis as essential to avoiding genocide. In November they brought together a small group of Dogon and Fulani women for a four-day retreat on violence prevention.

Women are key to solving the conflict, Cisse says: “It is their kids who join the terrorist groups.”

However, this appeared easier said than done. The women refused to share a taxi. And then bitter argument broke out over which side was responsible for the violence.

Aminata Diallow, a Fulani woman who was there, said the mood began to ease when both groups recognised that the time-worn ways of resolving disputes had collapsed and they needed to find other ways.

“We debated whether we should take matters into our own hands or go to see somebody else to resolve the dispute,” she said.

By the end of the session, the women had reconciled and swapped numbers.

“After the meeting we were very happy and forgave each other,” Diallow said.

But while progress is being made in Bamako, violence continues back home. Thirty-five Fulani herders were slayed last month by a suspected Dogon militia in Ogossagou, a town which suffered the worst massacre in recent memory almost a year ago.

And while they cannot go home now, a tyre attached to the trunk of a mango tree, half surrounded by a semi circle of tyres cut and placed on the ground, is a sign that they are making the most of what they have.

“Here is where the griot tells stories to the kids after dinner,” Cisse says, referring to the celebrated traditional West African storytellers.

“We don’t have to let them think about the tragedies. They can hear stories about work and about life.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.