Manchester bomber 'was not referred to Prevent' despite local concerns

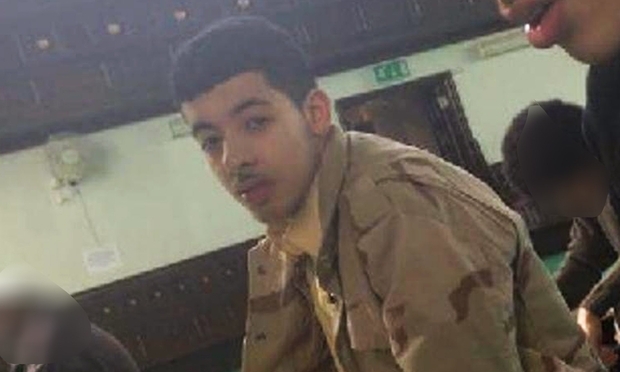

A suicide bomber who killed 22 people in Manchester on Monday had not been targeted by the Prevent programme, a report said on Friday, raising fresh questions about the effectiveness of the government's counter-extremism strategy.

A Prevent co-ordinator told the Financial Times newspaper that checks carried out revealed that 22-year-old Salman Abedi had never been referred to Prevent despite reports that members of the local community had reported him to authorities as someone of concern on several occasions since 2011.

Two former friends of Abedi, the 22-year-old British-born son of Libyan dissidents, told BBC News that they had twice called an anti-terrorism hotline, in 2012 and last year, because of concerns that he had expressed the belief that "being a suicide bomber was okay".

A community leader also told the Telegraph newspaper that he had reported Abedi to authorities “because he thought he was involved in extremism and terrorism”, while Abedi had also been banned from his local mosque in the Didsbury neighbourhood after confronting an imam.

Abedi had also travelled to and from Libya since visiting the country as a 16-year-old during the country's 2011 uprising against Muammar Gaddafi.

The Home Office told MEE that it could not confirm any further details about Abedi because investigations were ongoing.

But according to the Prevent co-ordinator, calls to the anti-terrorism hotline are supposed to be "triaged" between Prevent officers and regional police counter-terrorism teams to determine whether an individual is at risk of being "drawn into extremism" or actively involved in criminal activity, suggesting that Abedi was either deemed not to pose any threat or was referred instead to counter-terrorism police seeking to investigate and disrupt potential attacks.

Prevent is a strand of the government's counter-terrorism strategy that aims to reduce the threat of attacks by stopping "vulnerable people from being drawn into terrorism and extremism".

More than 4,600 people including children of primary school age were referred into Channel, a Prevent-linked deradicalisation programme, in the first year after the introduction of the Prevent Duty in 2015. The duty requires public sector workers including teachers and doctors to give "due regard to the need to prevent people from being drawn into terrorism”.Critics argue that Prevent is primarily an intelligence-gathering exercise targeted at Muslims, that it undermines free speech and civil liberties, and is counter-productive by alienating communities and undermining trust in the police and the security services.

Rudd: We get intelligence from Prevent

While the government has long argued that Prevent is effective and essentially about "safeguarding", Home Secretary Amber Rudd made a rare admission about the strategy's intelligence-gathering importance in comments on the BBC's Question Time programme on Thursday.

Questioned over whether budget cuts had reduced the police's ability to gather intelligence, Rudd said: "That is not where we get the intelligence from. We get the intelligence much more from the Prevent strategy, which engages with local community groups, not through the police. It is not about policing so much as engaging with community leaders in the area."

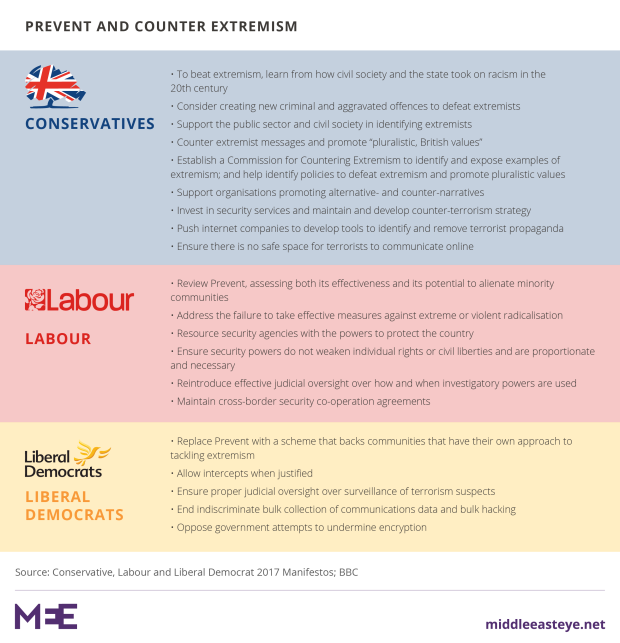

Rudd earlier this week pledged that the Conservative Party would fund an "uplift" in Prevent if re-elected in general elections on 8 June.

The main opposition Labour Party has called for a review of Prevent, addressing both its effectiveness and potential to alienate minority communities.

Questions have been raised about the methodology used within Prevent to identify vulnerable individuals, with the Royal College of Psychiatrists last year criticising the lack of transparency surrounding the strategy.

"Data on evaluations of Prevent, as with any initiative requiring public services to alter their practice, must be in the public domain and subjected to peer review and scientific scrutiny. Public policy cannot be based on either no evidence or a lack of transparency about evidence," the RCN said in a position statement.In a letter published in the Guardian last year, more than 400 academics said that assessment methods being taught to hundreds of thousands of public sector workers had “not been subjected to proper scientific scrutiny or public critique”.

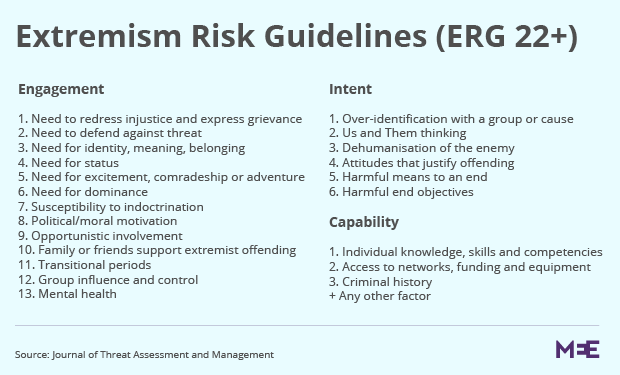

Individuals referred to Prevent and Channel are subjected to a "vulnerability assessment framework” based on a list of supposed factors in radicalisation known as the Extremism Risk Guidance 22+ (ERG22+) framework, which was developed by psychologists working with people convicted of terrorism-related offences.

Factors include "political/moral motivation", a “need to redress injustice and express grievance”, a “need for excitement, comradeship or adventure”, and “mental health”.

However the authors of the study on which the ERG22+ is based conceded in an academic paper in 2015 that the study lacked "demonstrated reliability and validity".

Greater Manchester Police has also faced criticism over the quality of its own Prevent training material which included a PowerPoint presentation featuring a mock-up of a "Terrorism Edition" of the board game "Guess Who?".

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.